From 24.05.2004 to 11.10.2004

Coinciding with the Olympics 2004, the exhibition “Imperial Treasures from China” in the National Gallery of Athens heralds the Olympics 2008, which are scheduled to take place in Beijing. It is a happy coincidence: The cities hosting the two consecutive Olympic Games are the cradles of two of the most ancient and most important civilizations of the Western and Eastern worlds respectively. Thus, this exhibition becomes a symbolic gesture―a tribute by the Chinese nation, heir of a cultural tradition of millenniums, to the Greek nation, responsible for safeguarding an equally hefty and lofty heritage.

These two cultures seem utterly different at first sight. Yet, the study of daoist cosmogony, which lies in the heart of Chinese culture, reveals a clear correspondence with the principles, concepts and motifs of Hesiod’s Theogony and subsequent pre-Socratic philosophy.

The primeval “dao,” identified with the “absolute emptiness,” reminds one of “Chaos,” the first state of creation according to the Theogony. The daoist “primal breath” suggests the irresistible creative breath of “Eros” in the Greek cosmogony. The Greek “Gaia” and “Ouranos” have a similar dialectic relation in Hesiod to the Chinese Yin and Yang1. The principle and discipline of logos enjoys prime of place both in the philosophy of Lao Tzu, the wise founder of Daoism, and in Heracletian thought.

Bestowed with moral character by Confucianism and identified with truth in Chinese aesthetics, the conception of harmony and beauty also evokes Heraclitus: The “hidden harmony” (Fragment 54), “better” than an obvious one, is the fruit of dialectics, dynamics, and of the perpetual synthesis of opposites: “What opposes unites, and the finest harmony emerges from opposing things, and all things are born out of conflict”2. “Nature may like opposites and composes harmony out of them and not out of similar things. Art, which imitates nature, seems to do the same”3. “Nothing more obvious than what is hidden, nothing more evident than what is obscure”4, according to Zhong Yong, a classic Confucian, echoing Heracletian thought.

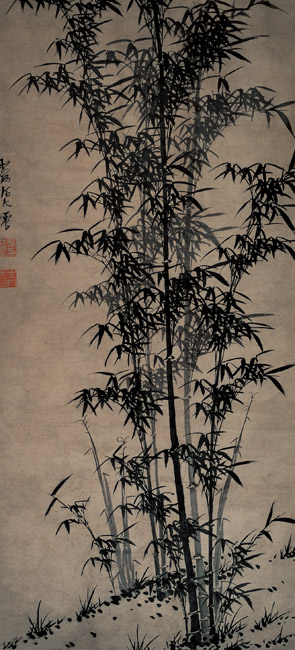

The Heracletian concept of “war”, the conflict of opposites, which results in the synthesis of harmony, also informs the entire Chinese philosophy. Daoist aesthetics regards a work of art as the ideal space for the synthesis of opposite forces: yin-yun (combined breath), qi-yun (rhythmic breath), and shen-yun (divine breath, transcendental breath) must achieve harmony, expressing the synthesis of Yin and Yang realized in the ideal work of art. The identification between the concepts of beauty and truth endows Chinese artistic creativity with a moral quality aking to Platonic aesthetics. For the Chinese sensibility, art is a path towards the discovery of truth, a path of moral perfection. Such an art would have been welcome in Plato’s Republic, from which art had been abolished as thrice removed from truth, being an imitation of an imitation.

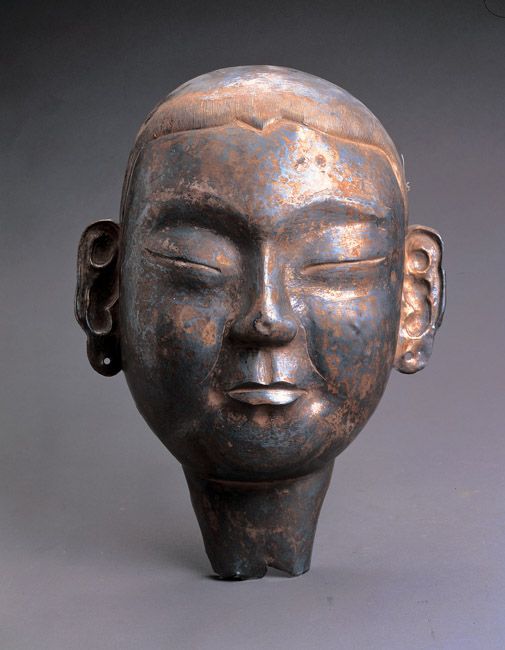

Yet, this may be where similarities end and differences begin. Nature lies in the centre of Chinese art from the very beginning. It is a pantheistic, deeply symbolic nature, whose elements correspond to the primal forces of Chinese philosophy. On the other hand, art in the Greek world is completely anthropocentric and nature is only hinted at. Another major difference between Greek and Chinese art is the relation between creator and creation. For the Greek antiquity, art is a cognitive path through the rational objectification of the world. According to Aristotle, art is a creative activity informed by logos. On the contrary, the dualism of Western thought does not apply for the Chinese artist. No line of distinction can be drawn between the artist and the work of art. Creative activity is the result of the same vital force which animates nature. Painting is a pantheistic communion of artist and nature. This is why in Chinese tradition artists often become one with their work and are annihilated, assimilated by it. Another difference is the precise codification of representational elements and the gestures of creative practice. What ultimately saves this art from being reduced to an academic exercise is the striking balance between traditional codes and an insightful observation of nature. An independent form of art in ancient Greece, sculpture enjoys prime of place, whereas in Chinese tradition it is subjugated to other creative fields―especially to painting.

A remarkable feature of the Chinese creative universe is its strong internal cohesion and unity. The same rules with painting apply to the supreme art of Chinese calligraphy, which becomes the ideal expression of painting, a cleansed manifestation of it. The images of things are expressed by ideograms in which the pure essence of things, their platonic ideas, are preserved. Calligraphers also practice painting.

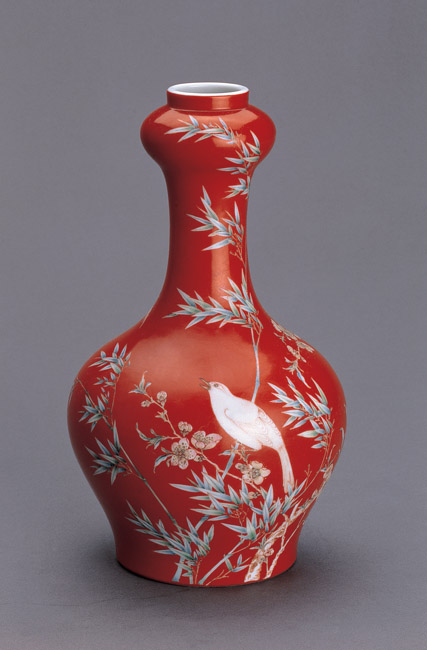

Beyond painting and calligraphy, the exhibition in the National Gallery of Athens aims to present a broad synthesis of the Chinese cultural heritage, from the wonderful bronze ware of its early history to the refined ceramics, which went through so many flourishing phases, such a wealth of techniques. Chinese ceramics never fail to amaze us with the ingenuity and harmony, their rhythmic patterns and sensitivity of colors, their decorative wealth, ranging from stylization to a vibrant naturalism. Miniature statuary, and the remarkable terracotta statuettes, as well as jade, and the marvels sculpted in this magical gem, are represented in this exhibition as well. Also on show are items of clothing, often from imperial wardrobes, which help complete the portrait of a civilization in which the ritual element has always played a major part. A privileged position is also reserved for Chinese Buddhist art, particularly sculpture, which was influenced by the Hellenistic art brought by Great Alexander’s conquests.

A few years ago, in 1988, with Dimitris Papastamos as Director of the National Gallery, the public had an opportunity to admire some of the imposing figures of the terracotta army unearthed in Xian. The exhibition presented in the National Gallery of Athens to mark the unique occasion of the Olympic Games aspires to present a more complete view of the great civilization of faraway China. Many people have contributed in order to make this possible. First of all, those who have had the vision and the initiative; most important, those who have worked in order to implement it. We would like to extend our thanks to Mr. Yiannis Theofanopoulos, Greek Ambassador to Asia and Oceania, Mr. Mei Ninghua, Director of the Cultural Heritage Office in Beijing, and Deputy Director Mrs. Yu Pin, as well as to the Museum Directors, Mrs. Yang Ling, and Misters Cui Xuean, Cao Pengcheng, Li Dengzhong. Also, to the Chinese team editors, Jiang Qiqi and Yuan Shankai.

Marina Lambraki Plaka

Professor of History of Art

Director, National Gallery of Athens

2. Heraclitus, Fragment 8

3. Heraclitus, Fragment 10

4. See Jacques Giès, “Peinture chinoise et représentation du monde”, in catalogue Trésors du Musée National de Taipei, Ed. de la Réunion des Musées Nationeaux Paris, 1998, p. 259 Exhibition Curator: Zina Kaloudi, Curator, National Gallery of Greece

1

2

3

4

5