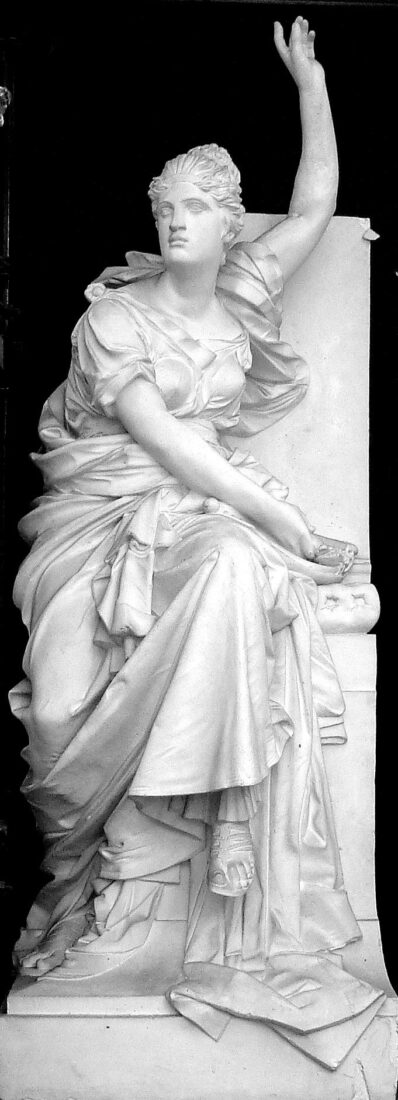

Ioannis Vitsaris was a sculptor who, along with Dimitrios Filippotis, transcended the limits of neoclassicism which then dominated modern Greek sculpture and introduced realism. In the First Cemetery of Athens are to be found certain of his most representative works, such as the “Mourning Spirit” on the family tomb of Nikolaos Koumelis.

The “Mourning Spirit”, the angel of death comes, as an iconographic type, from Hellenistic and Roman tomb sculpture and was a motif particularly dear to the hearts of makers of neoclassicist funerary monuments. It was brought to Greece by the German sculptor Christian Siegel. In the form introduced we see a naked angel, standing in relief, holding a torch upside down, symbol of life that has been extinguished. This original motif was subsequently varied and enriched with other funeral symbols, such as the seeds of the poppy – indication of eternal sleep – and the butterfly – symbol of the departing soul. Fully carved, it represents him seated in a thoughtful pose or fallen face forward and mourning, holding an urn of ashes.

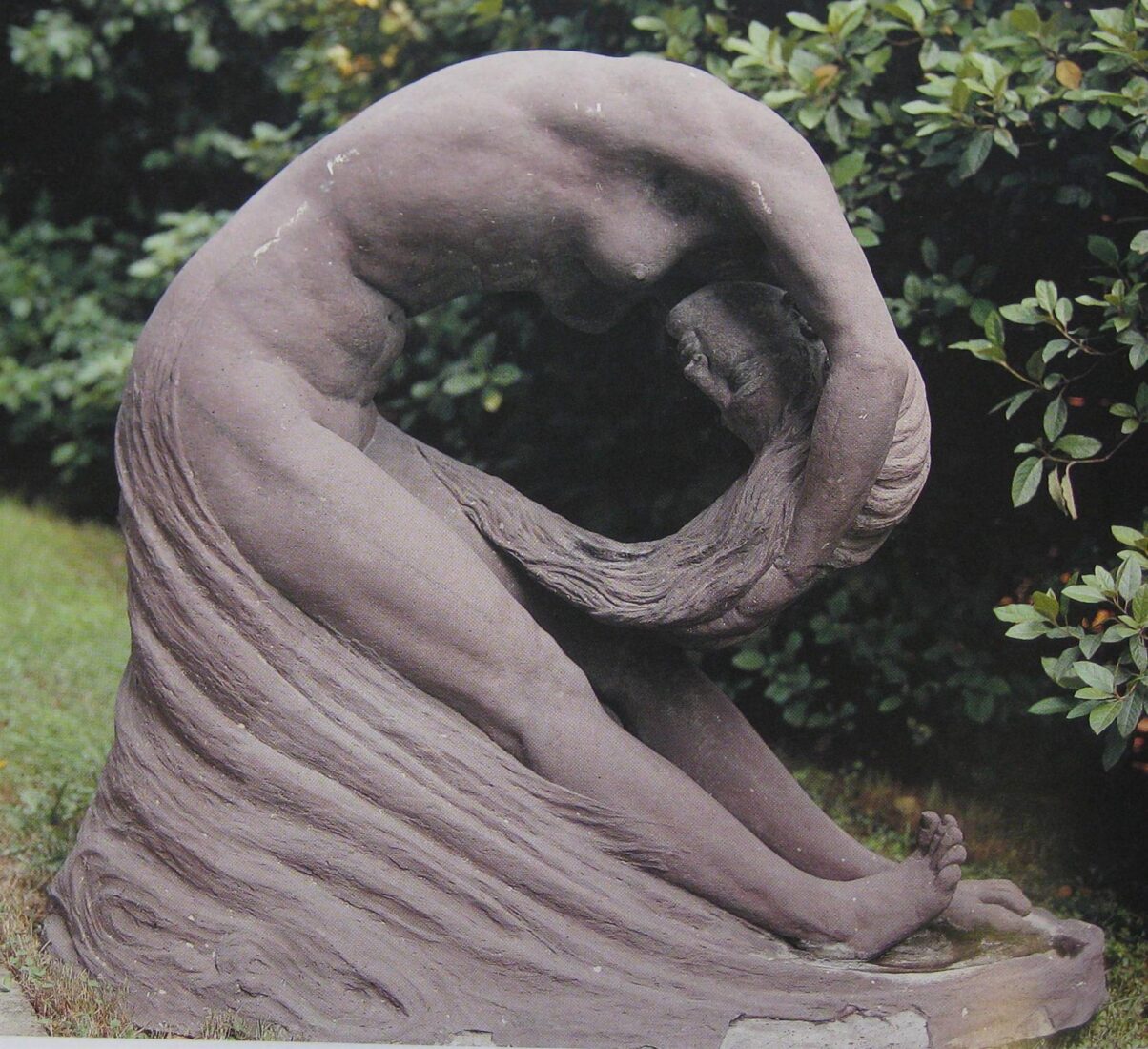

Ioannis Vitsaris based himself on the latter type, but stripped of any supplementary element or symbol. It is thus adapted to the realistic style, which aspires to express emotional situations by means of the work itself without the use of standardized symbols. His “Mourning Spirit”, having grieving “Morpheus” by Jean-Antoine Houdon as its iconographic model, is itself transformed into a symbol of grief and mourning as, fallen on the tomb, with his head on his right arm and his body tucked into a ball, the figure mourns for the dead person.

Manolis Tzombanakis focused on the human figure right from the start of his career. At the same time, he preferred to express himself through representation, but with a non-figurative bent, forming his own personal style from early on. His subjects, taken from everyday life, history or myth, often have an allegorical content or constitute a means of protest on a social or political level.

The compositions with horses or mounted figures, to which “Bucephalus” belongs, occupied him from 1972 to 1979 and despite the fact they can be connected to Greek tradition, in reality they were inspired by the Uprising at the National Technical University of Athens in 1973, against the dictatorship. Tzombanakis wanted to express the burden this dramatic event in recent Greek history placed on him as well as his protest against tyranny of any kind by using symbolic elements from other periods, but with clear allusions. “Bucephalus”, the unruly horse of Alexander the Great that only he managed to tame, is built of geometric volumes and is rendered in an intense and daring movement, expressing the momentary, an element which characterizes the artist’s compositions during that period, and echoes the dynamic movement hidden in the works of the Futurists and especially those by Umberto Boccioni.

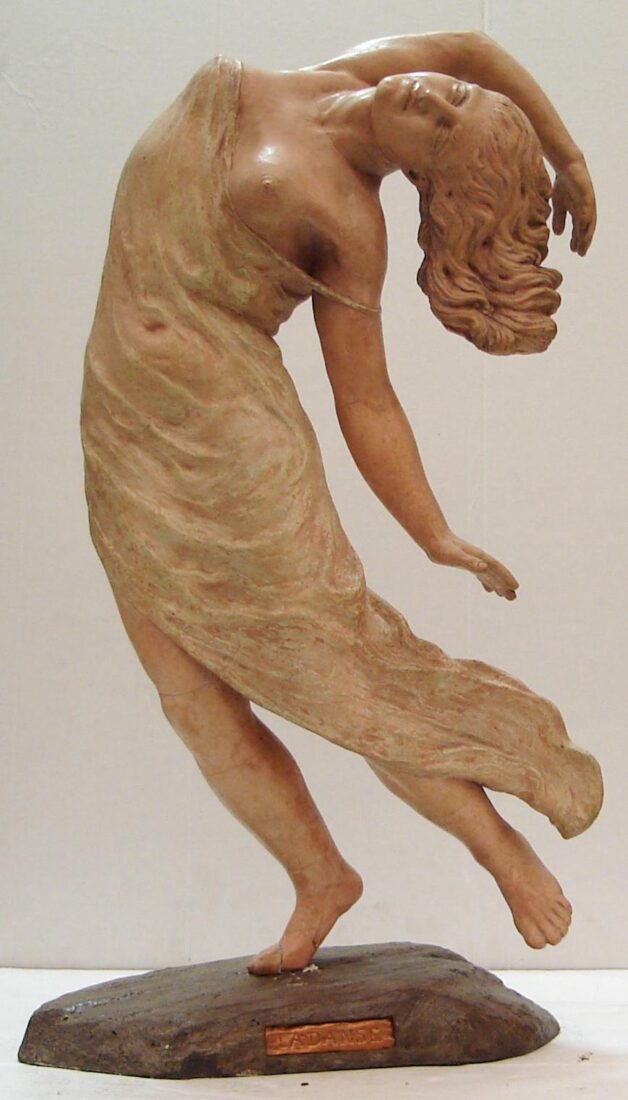

Even though he died at the age of forty, Yerassimos Sklavos left behind a rich and comprehensive body of work, largely based on research and on experimentation with the processing of materials. Until 1959, he was mainly concerned with the depiction of the human figure, first in a realistic and then in an abstract and stylised approach, as the artist had an inclination towards abstraction, and therefore his adoption of abstract forms was only a matter of time. From this period comes “Icarus”, made in plaster before 1957, when he left for Paris on a Greek state scholarship. Whereas other figures of the same period are modelled in serene and balanced poses, “Icarus” masterfully combines in a single perpendicular motion the rise and fall through a blurring of the lines between limbs and wings and the dramatic convolution of the body.

Lazaros Lameras was among the vanguard of abstraction in Greece. His stay in Paris in 1938-1939 played a definitive role in this choice.

He created his first abstract works in the period 1945 to 1948, among which was “Penteli”. The work originally carried the poetic title, “Penteli in Ecstasy” and as such was shown in the first postwar Panhellenic exhibition of 1948. In fact, it was the first abstract sculpture to be formally exhibited in Greece.

The inspiration for the piece was the mountain in Attica that had provided the marble for many important works of sculpture dating back to antiquity. Lameras has carved a small composition that combines vertical and horizontal motifs with gentle curves and an almost perfectly smooth surface, thus arriving at a pure form that echoes the enterprise of Constantin Brancusi.

Antonios Sochos was one of the first sculptors to distance himself from neoclassicist doctrines and turn in a completely different direction. His study of archaic plastic art from the 7th and 6th century BC, of Cycladic figurines, as well as Gothic art, coupled with his initiation into the long tradition of folk sculpture on Tinos in combination with an acquaintance with the avant garde movements in Europe were the sources of his inspiration.

“Girl” is a work that makes a clear reference to early archaic sculpture, to effigies and even to Egyptian art. The pose assumed by the young figure, frontal and static, practically without depth, points to a distant model in the “Lady of Auxerre” from the 7th century BC and “Hera by Cheramyes” from the 6th. The right hand, holding the folds of the garment, is the only element breaking the absolute immobility, while the surfaces are for all intents and purposes flat, with the exception of the emphasis on the chest, the light grooving suggestive of drapery and the engraved decoration on the bottom part of the tunic. The carving was done directly on eucalyptus wood. The use of wood in a large number of Sochos’ works is a further indication of the artist’s innovative thrust and connects him both to the folk sculptors who made figureheads for ships and the primitivist perceptions which then held sway in Europe.

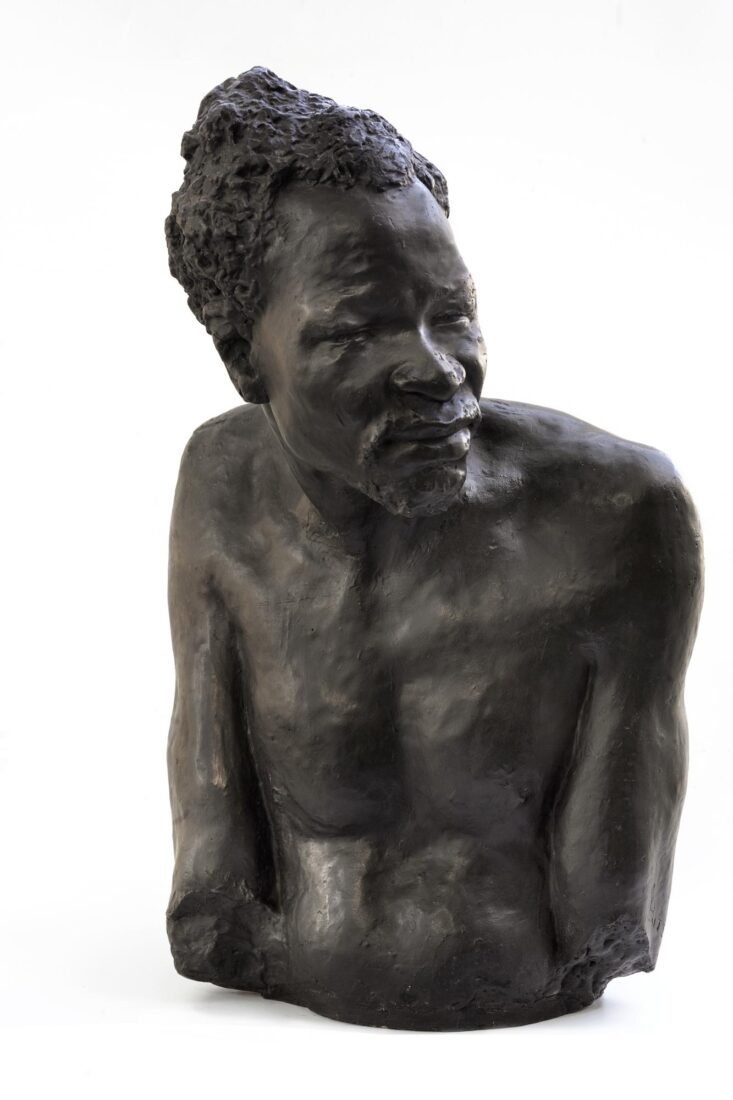

Ioannis Vitsaris studied at the School of Arts and completed his education in Munich. Despite his neoclassical education, returning from Munich in 1871, he engaged in realistic compositions, both in terms of content and style, often much bolder than those of Dimitrios Filippotis, who was the first to introduce realistic themes into modern Greek sculpture.

“Christos, the Black Guy” belongs to this category. Christos was a characteristic figure of Athens, who lived mainly on the streets and died in 1886. He was especially beloved, while he was a model in works by the painters Nikephoros Lytras and Nikolaos Gyzis.

Vitsaris made the work in 1874, with a very realistic style, which is reflected in the posture of the body and the rendering of details, while the painted plaster creates the impression of dark skin. In 1875 he presented it at the Olympia exhibition, where he won the bronze medal. But despite the award, it was described by the critics as an “unfortunate idea”. Despite the negative reception, however, “Christos, the Black Guy” is an exceptional, and early, sample of realism in modern Greek sculpture, without concessions in the neoclassicist direction.

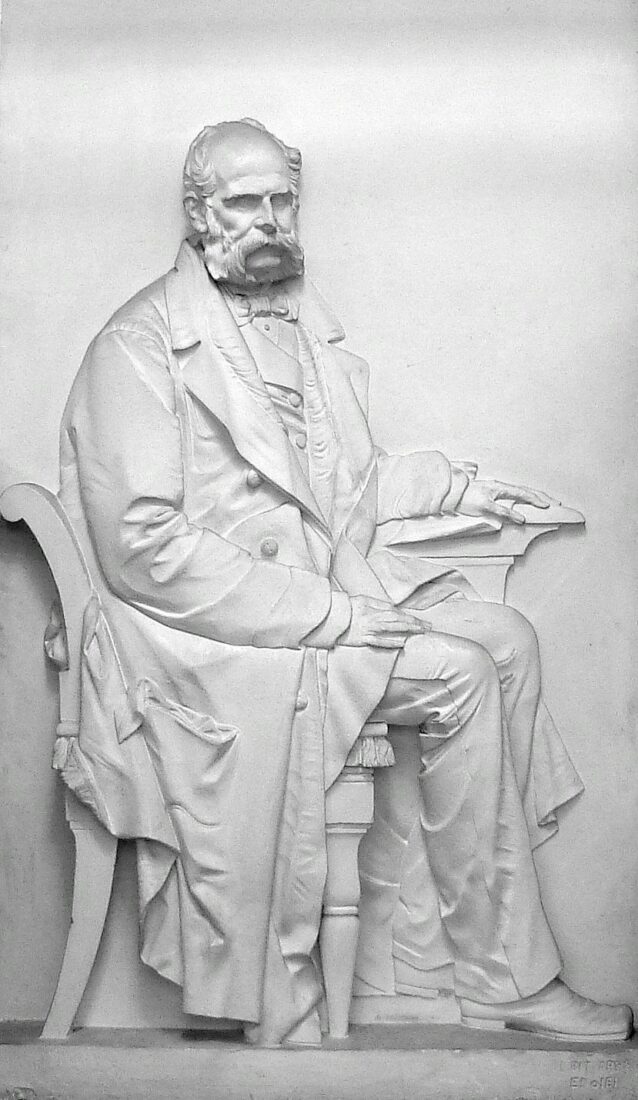

Ioannis Vaptistis Kalosgouros belongs among the Ionian island artists who revived the art of sculpture in the Ionian, creating the first works of modern Greek sculpture.

The bust of the illustrious Hellenist and Philhellene Frederick North, Count of Guilford (1776-1827), who in 1824 founded the Ionian Academy on Corfu and with whose financial assistance a number of later to be illustrious Greeks studied abroad, is almost a faithful copy of the bust Pavlos Prossalentis had made in 1827. The English Philhellene is depicted wearing the specially designed ancient-style uniform of the Lord of the Ionian Academy. His mature age is expressed by the wrinkled cheeks and the stringy but at the same time rather loose neck while his gaze is fixed, in keeping with the neoclassicist model. The thin hair on his head is framed in relief by a decorative band with an owl in the center, the symbol of education. The imposing rendering of the figure expresses self-confidence and satisfaction and stresses the count’s dynamic personality.

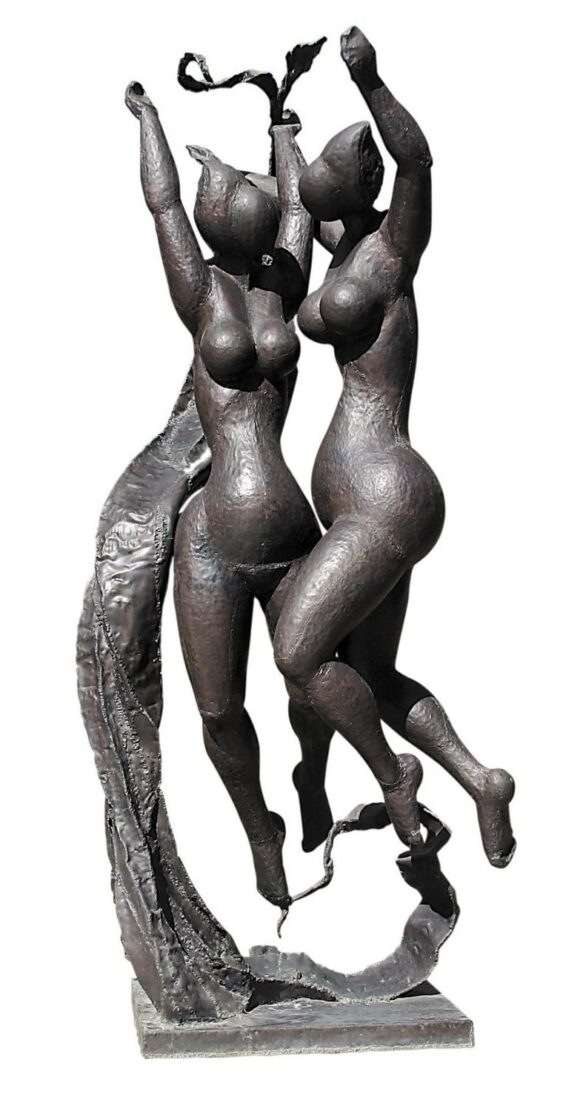

A sculptor who centered his attention on the human figure, faithful to representation but with a strong tendency toward the schematic and the abstract, Memos Makris studied at the Athens School of Fine Arts, and then attended lessons in the studios of Jean-Paul Laurens and Marcel Gimond in Paris, where he lived for five years, settling in Hungary in 1950. Busts, female figures, nudes, and monuments designed for public spaces, made up the core of his work, which drew elements from both archaic art and his French teachers and, occasionally, abstract and expressionist models.

In 1965 he began working on a number of naked figures. These figures are rendered very schematically, with oval heads and sometimes with the characteristics of their physiognomy simplified, and other times without any characteristics at all, with the bodies all worked the same way, with rounded volumes and elongated forms. The “Spring Dance” follows along these lines, but the abstract rendering is even greater, while the two figures hover in the air in a laudatory dance in honor of spring, recalling scenes from the three Graces in compositions of European art.

Giorgos Zongolopoulos worked with figurative depiction centered on the human being for a considerable period of time before moving on to completely abstract compositions. The realistic portraits he did, by and large before 1940, were succeeded by full-bodied figures with a steadily growing intensification of the simplified and schematic forms, particularly apparent in the Fifties.

In 1956 Giorgos Zongolopoulos represented Greece at the Venice Biennale with the work “Composition for a dramatic subject”. Still working within the framework of representational art, but with an equally intense schematization evident, this time concentrated in elongation, he created a composition with two standing figures, one dressed as a female, erect, frontal and taller, and a nude male, who is about to fall but is held up by the woman, who embraces him protectively. This composition, with the flat rendering of the surfaces and the incorporation of geometric shapes without volume, would be the forerunner of non-figurative works that would follow during the Sixties, done from a constructivist point of view. The composition that belongs to the National Gallery is a variation in a smaller scale of the work exhibited at the Venice Biennale and is a gift of the Ministry of Education in 1967.