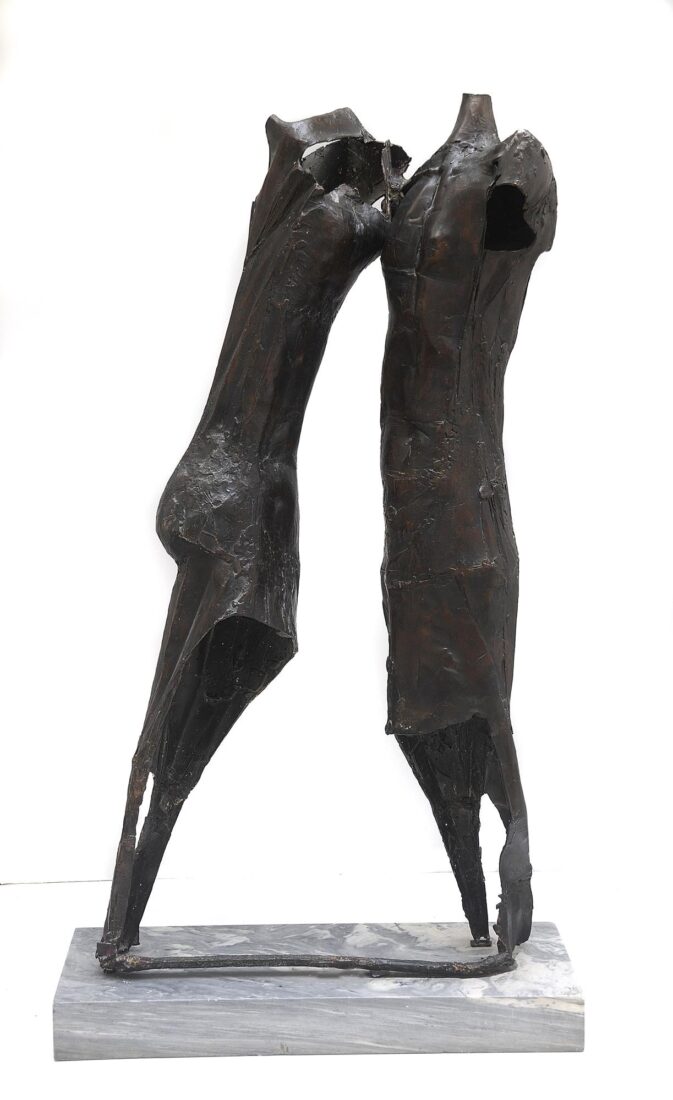

Achilleas Aperghis started out with figurative depictions centered on the human figure, full-body or bust, and then proceeded, mainly after 1950, to more abstract “anthropomorphic” shapes, finally reaching a non-figurative form of expression. Abandoning traditional materials, he followed the trend of the times and turned to iron, bronze and the smelting and welding of metals. The develoyment of the form in space, horizontally, vertically, or diagonally, was of especial interest to him in his endeavor to create an impression of flight. His preoccupation with the field of non-figurative expression would later lead him to the rejection of conventional sculptural depiction and to a conceptual approach to problems, expressed through environments and installations, directly connected to his existential anguish.

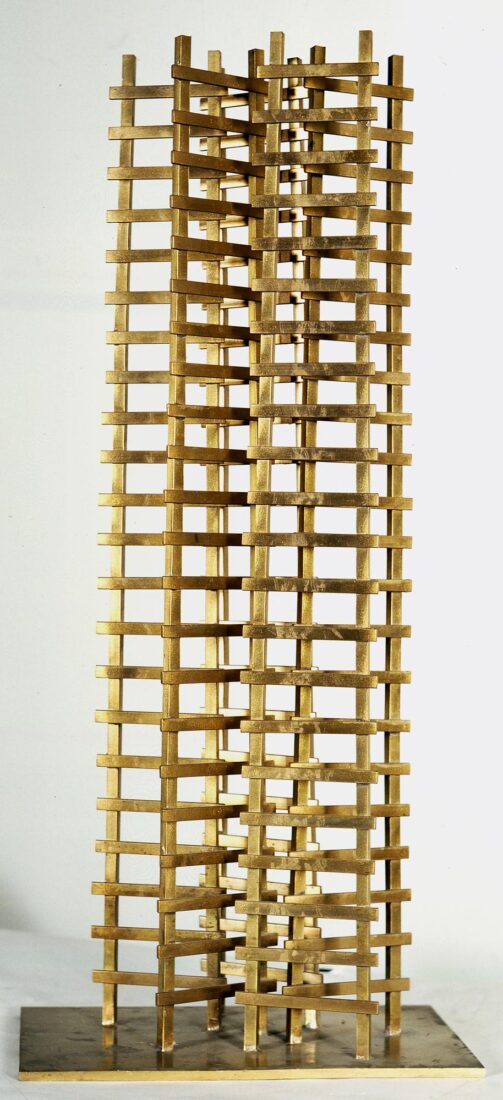

His environments with “Ladders”, which were presented for the first time in 1978, first in wood and then in bronze, but also as isolated compositions containing ladders of various sizes, were the result of his quests in the field of environments and installations, combined, however, with his return to the use of elements of figurative representation, and constitute signs of ascent and endeavor, suggesting an outlet for knowledge.

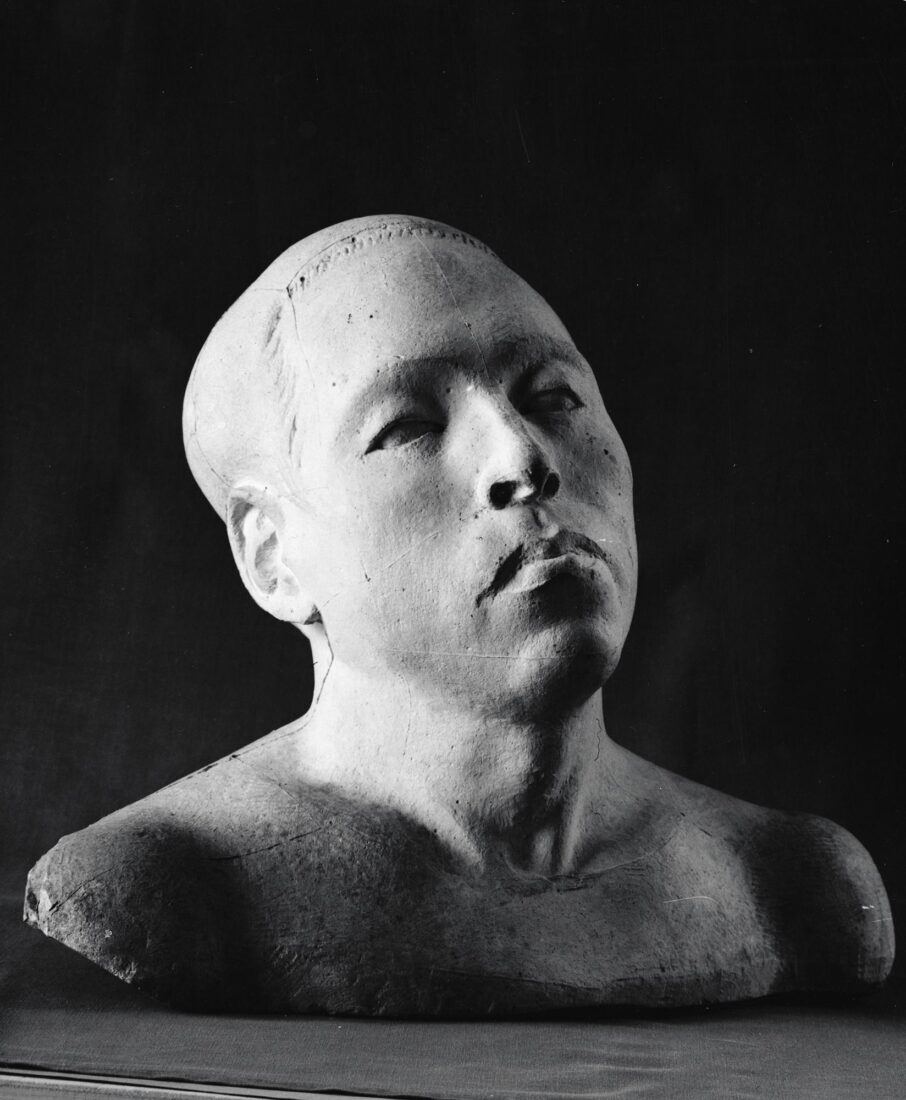

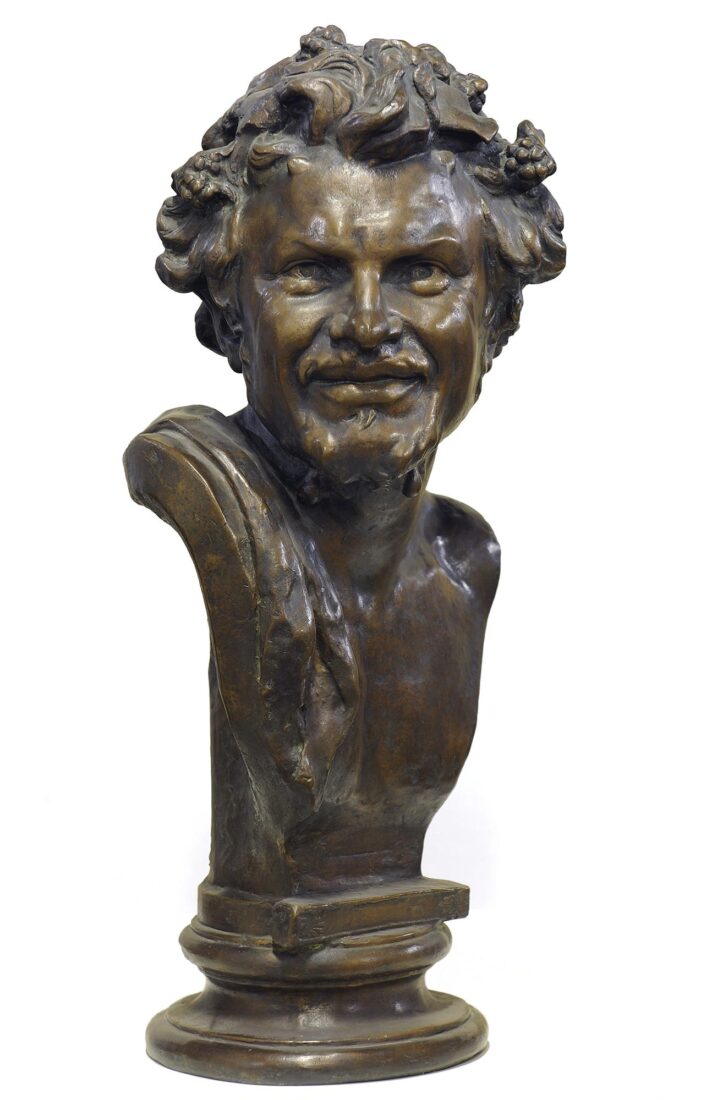

Yannoulis Chalepas was a uniquely gifted artist. But his life and artistic development were marked by the manifestation of mental illness that led to confinement in a psychiatric hospital on the island of Corfu and a forty-year hiatus in his artistic production. The first symptoms of aberrant behavior presented in 1878, the same year that he completed his first body of work, referred to by historians as the “first period.”

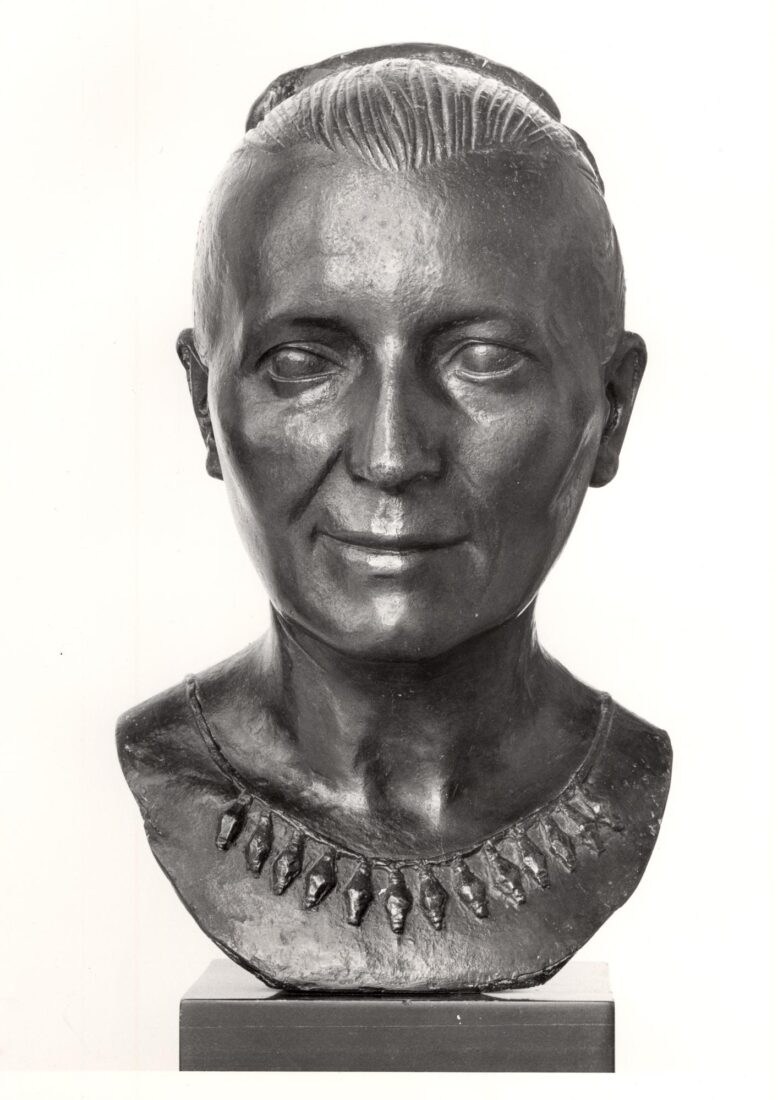

“Satyr’s Head” is among the last works of Yannoulis Chalepas’ first creative period. A realistic, highly modeled figure, it is a virtually psychographic, personal portrait of a mature man. The vivid, penetrating gaze and enigmatic smile establish the figure’s personality. The smile appears at once sarcastic or demonic and melancholy, depending on the angle from which it is regarded. In fact, this piece caused Chalepas such emotional distress that he tried to destroy it by scratching and throwing clay at it.

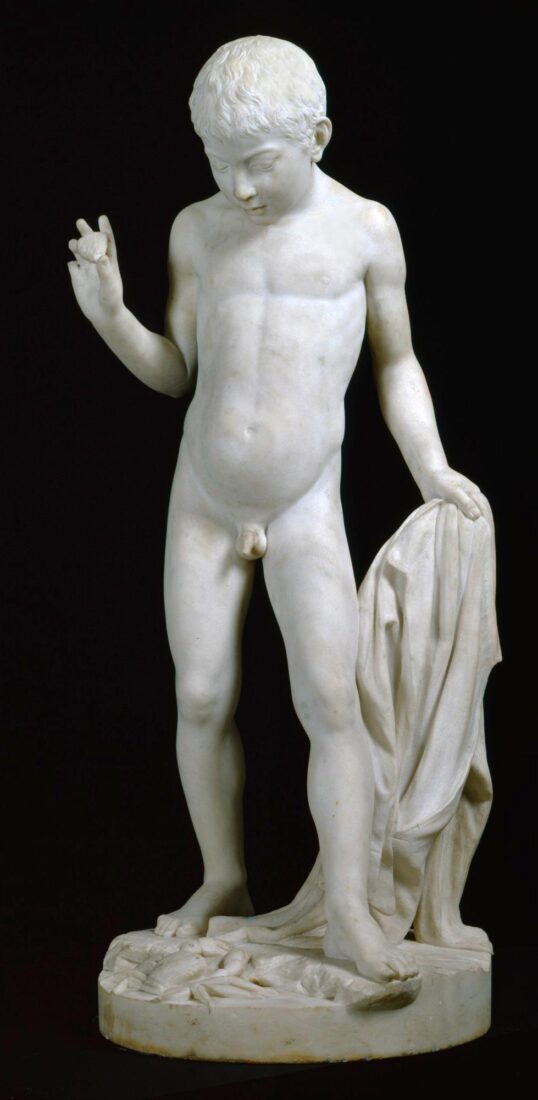

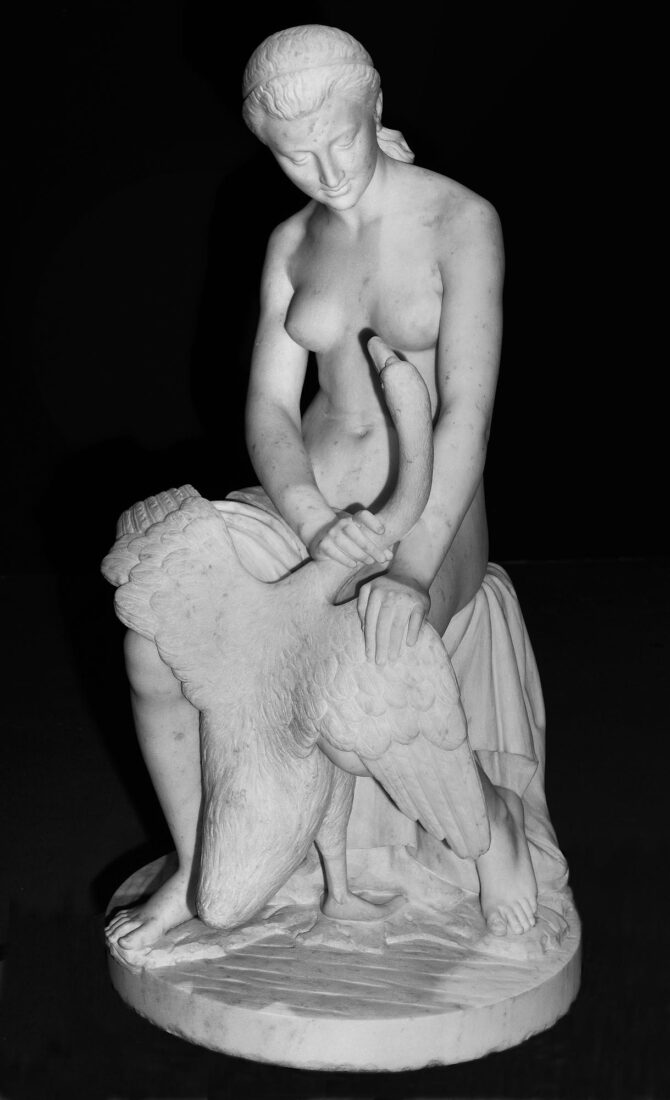

Leonidas Drossis belonged to the first generation of modern Greek sculptors who studied at the Athens School of Arts and were shaped in the spirit of neoclassicism that was brought to Greece by the German sculptor Christian Siegel. Broadening his education at the Munich Academy under Max Widnmann and with trips to Paris, London, Dresden, Vienna and Rome, where he opened a workshop, he would prove to be the most important representative of Greek neoclassicism.

During his residence in Munich, Drossis became acquainted with the founder of the Academy of Athens, Baron Simon Sinas. In 1860 Sinas decided to offer him the commission for the construction of the four pediments on the Academy as well as all the sculptural decoration of the building later on. In the end, Drossis did only the central pediment, whose theme was the “Birth of Athena”. During that same year he presented the model at the Olympia exhibition along with two earlier models, winning the gold medal.

The seated figure of Zeus commands the center of the composition, framed by Athena and Hephaestus, while a little further on Hera observes everything jealously and at the same time Iris is ready to make her joyful announcement of the birth. The remaining groups are connected with the central composition and the ends are closed off with the figures of the rising sun and the falling night. The composition is done in complete agreement with the spirit of neoclassicism and, just as the rest of the decoration of the Academy, serves as a symbol of Greece reborn, while the sculpture itself constitutes an indissoluble part of the architecture done in agreement with ancient prototypes.