“The Spirit of Copernicus” is a unique example of an early and exceptionally daring composition for the Greek public. Vroutos made the plaster model in 1873, while he was in Rome, and in 1875 exhibited it at the Olympia exhibition, where he won the “silver medal second class”. In 1878 he presented it at the International Exhibition of Paris, while in 1881 at the exhibition held at the Vassilios Melas mansion for the benefit of the Red Cross.

The spirit of the leading astronomer, who reversed the dominant theory by claiming that the earth and the planets move around the sun, and not vice versa, is depicted in an equally subversive composition: an inverted winged young figure leans against the terrestrial globe with its right hand, while spinning it at the same time. He points towards the sun with his left hand. The inverted figure with its legs in the air was already known from the Hellenistic composition of the “Boy with the Dolphin” (Roman copy at the National Museum of Naples), from which Vroutos borrowed the stance of the boy, as well as the embracing of the head of the dolphin. A similar stance, originating from a Roman composition, was repeated in the work by Canova, “Hercules and Lichas” (1795-1815, Galleria Nazionale d’ Arte Moderna, Rome). The winged figure, moreover, which symbolizes the spirit of an eminent figure and supports itself on a globe, was already known from Descartes’ cenotaph at the church of Adolf Fredrik in Stockholm, by the Swedish sculptor Johan Tobias Sergel (1740-1814). In any case, for the Greek public, this composition was exceptionally daring and the endeavor was not carried on any further.

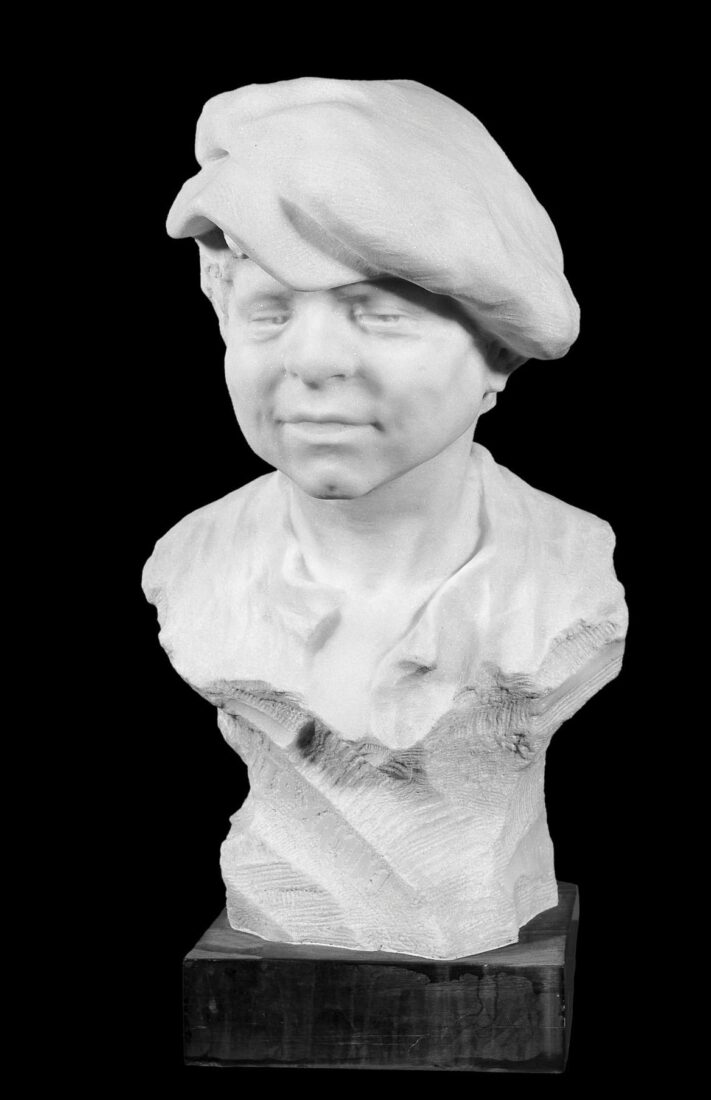

Loukas Doukas, who died before his time, was an artist faithful to the rendering of the human figure. He lived during a transitional period in modern Greek sculpture, moving from neoclassicism to realistic depiction. From early on, he produced worthy examples, influenced primarily by his studies in Paris, where the plastic style of Rodin and his successors held sway.

In “Street-Urchin”, a picturesque street figure, the plastic doctrines of Rodin are combined with a naturalistic rendition of a realistic subject. The picturesque figure of the young boy with his cap, carved along with the base from a single piece of marble, projects out from the unworked lower part and is moulded with fluid contours and soft surfaces, where the stress is on the tranquility of the child’s features in contrast to the artist’s other compositions which adopt a violent, expressionistic distortion in order to correspond to the content of the subject.

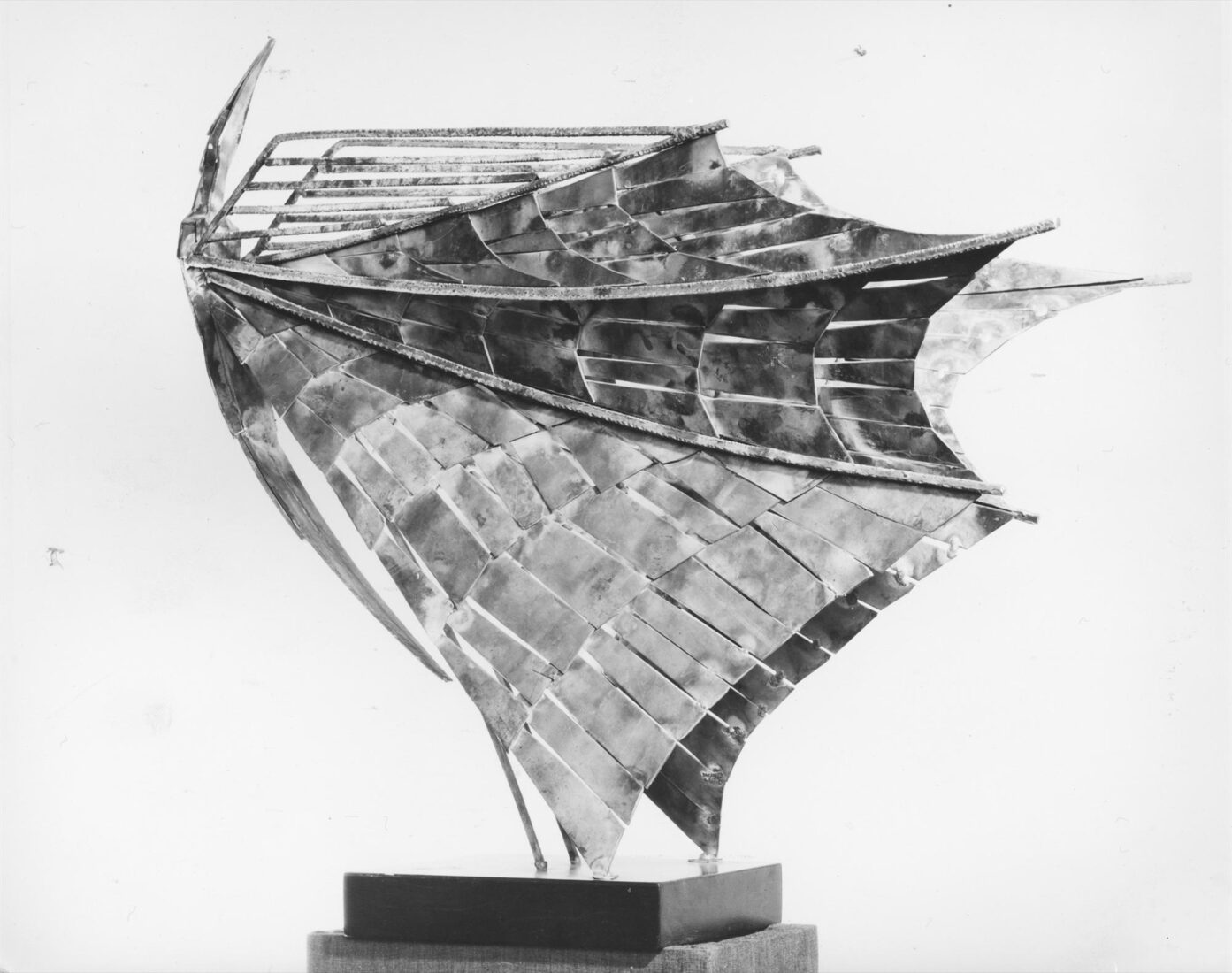

Froso Efthymiadi studied pottery-making in Vienna and for a long period made works exclusively in terracotta in a realistic manner. In 1955 she abandoned terracotta and turned to the use of metal, while the realistic rendering began to lessen and the figures became very abstract, but without the physical form itself becoming unrecognizable.

The female figure provided the spark for the creation of a multitude of both small and large compositions which, sometimes static and other times in motion, set forth the personal view of the sculptor in regard to the rendering of female charms.

From around the end of the Fifties she started using hammered metal rods. The rods were welded together having empty spaces left between them, thus allowing space to enter the work and become a dynamic element in the composition. A “Nike” from 1960, done in hammered bronze and reshaped into practically a straight line, is an ethereal and dynamic form of the ancient image of the “Winged Victory (Nike) of Samothrace”, as it surges forward freely and impulsively and is imposed on space with the assistance of the empty space, which is spontaneously transformed into a natural background. In 1969, the rendering of movement became even freer, as the bronze rods were polished, widened and transformed into ribbons which bend and wind around empty space suggesting the body in “Nike II”, which now seems not only to be rushing ahead but to also be swirling around in a victory dance.

Frosso Efthymiadi studied ceramics in Vienna and for a long period made realistic works exclusively in terracotta. In 1955 she abandoned terracotta and turned to using metal. At this time her work became very abstract, but the physical form always remained recognizable.

The female figure sparked the creation of many small and large compositions. Sometimes static, elsewhere in motion, these pieces formulate Efthymiadi’s personal view of the harmonious rendering of female grace.

“Lot’s Wife” is her only work that portrays a religious figure. For its rendering, Efhymiadi borrowed the shape of an organic form – a tiny ordinary seashell. With this she conveyed the pure form of a woman who turned into “a pillar of salt.” The very shape of the shell offered the solution for the creation of the work, with its endless coiling and uncoiling. Schematic but totally recognizable, “Lot’s Wife”, wound in her cloak, stands petrified, motionless and silent.

The realistic and at the same time psychographic rendering of the depicted person in busts, which had already come to dominate Europe, pricked the interest of Filippotis as well, who during the period 1864-1870 was continuing his studies in Rome.

The bust of Eirene Abanopoulou, a beautiful young woman, is rendered in a practically generalized manner in regard to her nude upper chest and shoulders, which are moulded with soft curves and slight protrusions and depressions of the marble surface, but with an especially dexterous manner in the rendering of the smooth and vibrant young flesh. The sculptor’s realistic approach is expressed most clearly in the rendering of the natural features, seen in the delicate eyebrows, the pupil and iris of the eye, the fine, well-proportioned nose and the small mouth, as well as the lacy border of the dress with the low neckline. This rendering reaches its crowning point in the elaborately worked hair-style, with the long braid wound around her head like a crown.

Georgios Bonanos lived in a period of transition for modern Greek sculpture. It was a time when a number of artists had begun abandoning neoclassical styles and subject matter in favor of realism.

“Nana” is a daring composition, inspired by Emile Zola’s novel of the same name. It displays the influence of this particular literary work on Greek art as well as Bonanos’ shift towards realistic subject matter. Nonetheless, the rendition remains neoclassical. The marble surface is highly refined and the heroine is depicted nude with a tranquil face that is almost indifferent to her body’s sensual pose.

Bonanos showed this work in 1900 at the Paris Exhibition, where it won the bronze medal. In 1938 he exhibited it in the Panhellenic exhibition at the Zappeion in Athens. Bold for its time, it provoked considerable debate. At any rate, the sculptor later changed the title to “Huntress”. This change was probably due to Bonanos’ Hellenocentric ideology, but also could have been his attempt to avoid scandal. Nonetheless, the dog, the lion’s skin, and the bow and quiver associate the young woman with Artemis, Goddess of the Hunt, “mistress” and “enchantress” of animals, who here becomes the temptress of men.

Thodoros Papayannis made the human figure practically his exclusive subject, but liberated from any trite naturalistic stylization. His knowledge of ancient Greek civilization and the broader Mediterranean region, Greek folk tradition and his post-graduate studies in Paris later on, nourished, by the stimuli they offered him, the formation of his style.

Using stone, marble, bronze and clay, he gave form to his earliest, tectonic compositions, which were formed by means of geometric volumes. From around the middle of the Eighties his tendency toward ever increasing schematization has been expressed through the use of more curved lines and he has thus been led to larger-than-life-size totemic figures, references to the imposing divinities of ancient civilizations which take their form through a combination of wood, iron, polyester fibers, and various metals, as well as readymade materials that are reused.

One particular entity of his work is the series “My Phantoms”, consisting of figures tragic and at the same time repulsive, made of old wood and iron, remnants of sections of the National Technical University burned by vandals in 1994, which express the artist’s protest against violence and waste.

Thodoros Papayannis made the human figure practically his exclusive subject, but liberated from any trite naturalistic stylization. His knowledge of ancient Greek civilization and the broader Mediterranean region, Greek folk tradition and his post-graduate studies in Paris later on, nourished, by the stimuli they offered him, the formation of his style.

Using stone, marble, bronze and clay, he gave form to his earliest, tectonic compositions, which were formed by means of geometric volumes. From around the middle of the Eighties his tendency toward ever increasing schematization has been expressed through the use of more curved lines and he has thus been led to larger-than-life-size totemic figures, references to the imposing divinities of ancient civilizations which take their form through a combination of wood, iron, polyester fibers, and various metals, as well as readymade materials that are reused.

One particular entity of his work is the series “My Phantoms”, consisting of figures tragic and at the same time repulsive, made of old wood and iron, remnants of sections of the National Technical University burned by vandals in 1994, which express the artist’s protest against violence and waste.