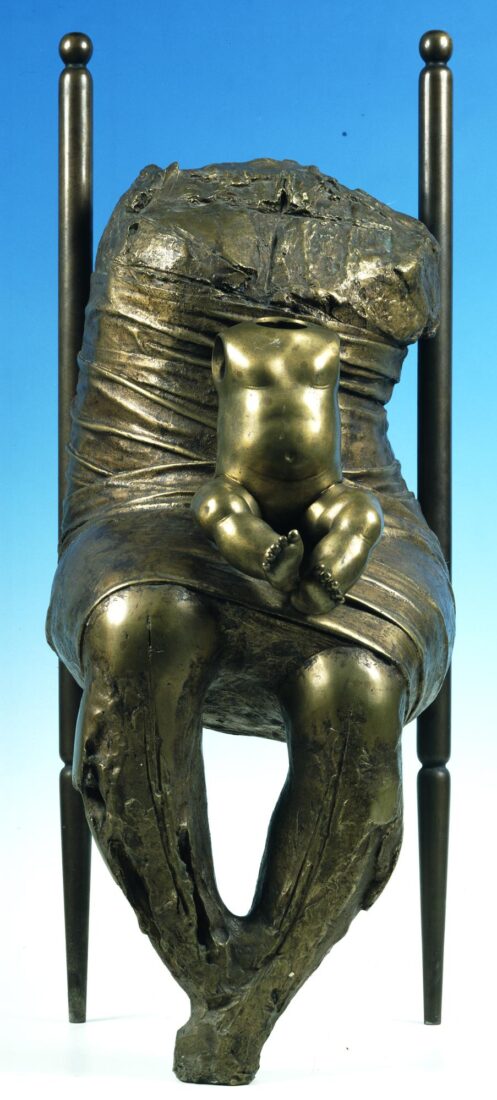

The seated female figure constitutes the basic subject in the sculpture of Giorgos Georgiadis. After a period in which he was involved with subjects taken from everyday life rendered in a highly generalized fashion, without any emphasis placed on detail, he adopted an expressionistic style, radically distorted, which has come to characterize his work since the end of the Sixties. The main subject now is a ponderous, fleshy female figure, usually headless and armless, with a broad lap and thick legs with large cracks in them, without feet, and wrapped very tightly in a piece of fabric leaving the breasts naked. This figure, whether seen in isolation or in combination with other figures, is transformed into a symbol and means of expressing criticism or protest regarding current social or political situations. The series “Paean”, which employs the well-known female figure, repeated in a variety of laudatory attitudes, as expressed through the figures’ uplifted arms, the lute and the drum, comes as a retort, meant to express an optimistic outlook and to send a message of hope.

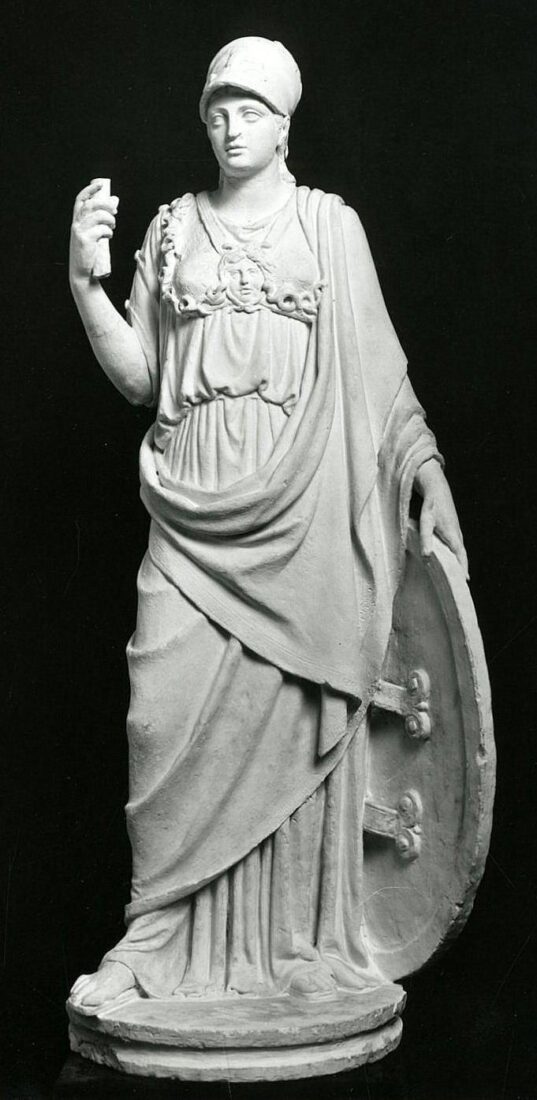

The neoclassicist education of Georgios Vroutos, as well as the admiration he felt for the work of neoclassicist sculptors and particularly that of Antonio Canova, is apparent throughout his artistic career. This admiration can also be confirmed in the case of “The Fury”. Though a distant model can be seen in the ancient Greek “Nike” by Paionios, a more direct and unambiguous model is “Hebe” (1796-1817) by Antonio Canova.

Vroutos made the work in two copies. In both instances the woman has a furious expression and wings spread in a violent movement, creating the impression that she is practically on top of the waves, while the ancient-style garment, which is fluttering, leaves the body almost completely naked. Snakes are coiled in her hair, an element which connects her to the ancient Greek Furies which are identified with remorse. Their mysterious voices reputedly gnawed at the soul and the mind and caused powerful inner disturbances. The difference is that in the one copy the woman is holding a trident in her raised hand and a lightning bolt in the other, while at her feet is a boat which is sinking in the waves, an event identifying her with the figure of the Tempest. In the copy on exhibit at the National Glyptotheque, conversely, the figure is more likely to be identified with the Fury, since the trident and the lightning bolt do not exist while the woman flies above the waves without the boat being depicted.

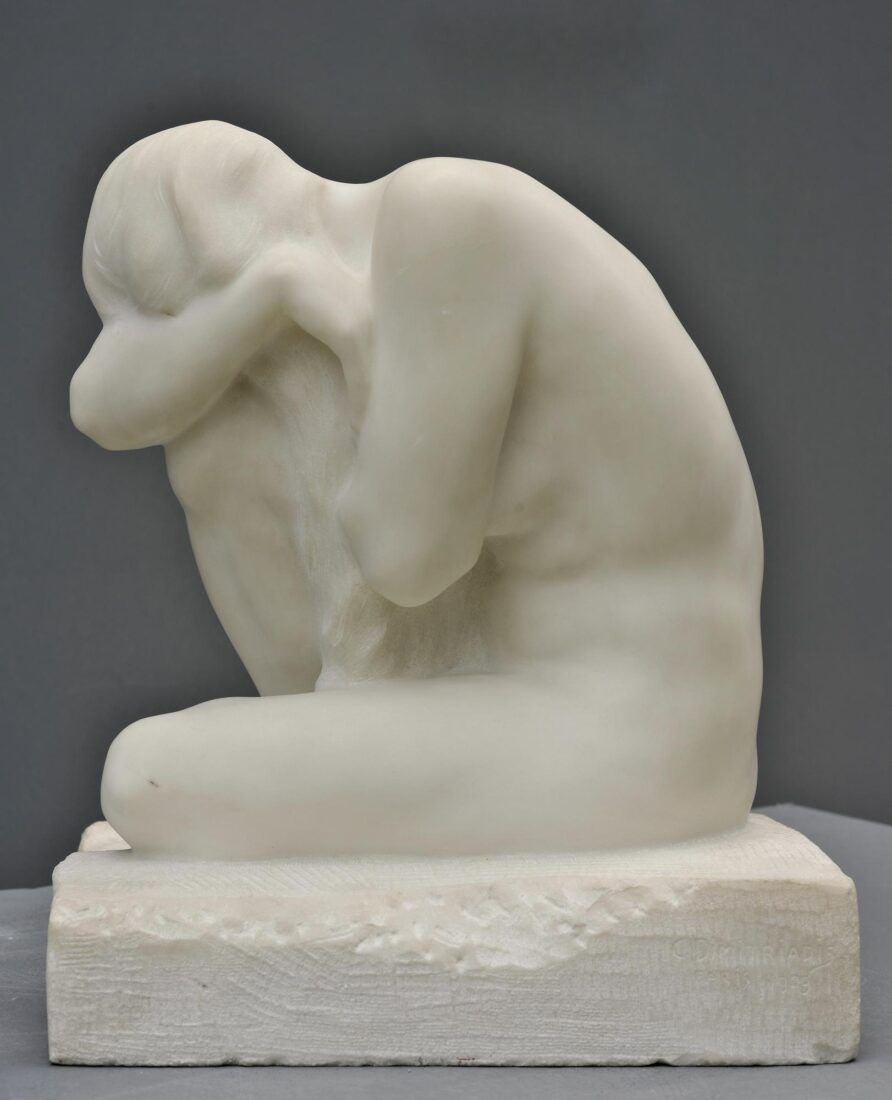

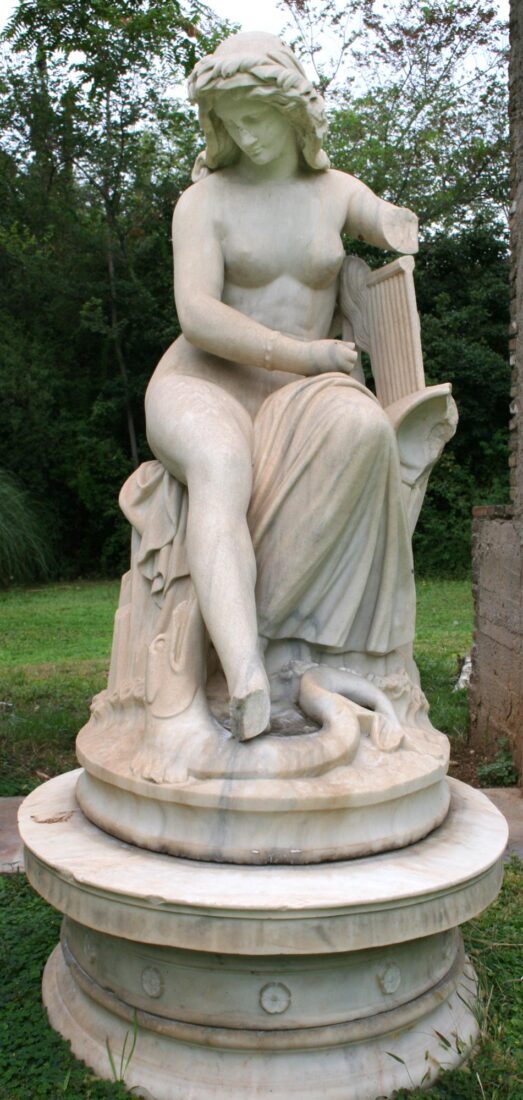

In 1949 Nikolaos G. Iliopoulos presented six marble sculptures to the National Gallery; he had inherited them from his uncle Nikolaos I. Iliopoulos and they had been placed in the garden of the former Thon villa, which was destroyed in December 1944. These sculptures are signed works – four by Georgios Vroutos and one by Georgios Fytalis. The only one that does not bear a signature is “Nymph”, but it was also thought to be a work by Georgios Vroutos and was recorded in the archives of the National Gallery under the title “Water-Nymph”, while in the report by the experts on the evidence obtained from the destroyed villa, it is referred to under the title “Fryni”. But the original attribution to Georgios Vroutos does not stand.

In 1841 the neoclassicist sculptor Ludwig Schwanthaler was commissioned to make a Nymph to be placed in a like-named room in the Anif Palace near Salzburg. Schwanthaler finished the work in marble in 1848. In 1852, with a few insignificant changes in the model, it was cast in bronze for the Royal Garden of Munich, while in 1855 the original or perhaps a copy was presented at the International Exhibition of Paris. In 1906 the original work was transferred from the Nymphs hall to the arcade of the palace where it fit in with the romantic exterior environment.

The “Nymph”, an idealized female figure with long wavy hair decorated with a wreath, is seated on a rock by the edge of the water holding her lyre with a melancholic and somewhat otherworldly expression, while a fish plays at her feet. The pose of the figure expresses thus the romantic spirit of the times in regard to the harmonious coexistence of the human being and nature, and brings to realization similar personal perceptions of the sculptor himself.

The “Nymph”, which came to the National Gallery in 1949, reproduces with almost perfect fidelity the original composition by Schwanthaler and leads to the conclusion that it is yet another copy of the work by Schwanthaler.

Sofia Vari started out as a painter but soon turned to sculpture. The human figure was her exclusive subject in her early works. Corpulent women, rendered with intense schematization and an absorption with the general elements which compose the figure, worked with powerful curves and a particularly heavily stressed fluidity of the volumes, were the precursors of the abstract compositions that were to follow. In these compositions, her interest is focused on subjects inspired by people or events in Greek mythology, while her style contains a number of influences, mainly from the work of Henry Moore and Jean Arp.

In “Centaur”, as in other works of mythological content, the subject is only the motivation for creating comprehensive compositions, based on curved and full volumes which seem to develop around an invisible nucleus surrounding it. Faultlessly smooth and polished, the volumes are combined and interwoven rhythmically, without angular interventions and interruptions of their alternations and thus form shapes spare and clean.

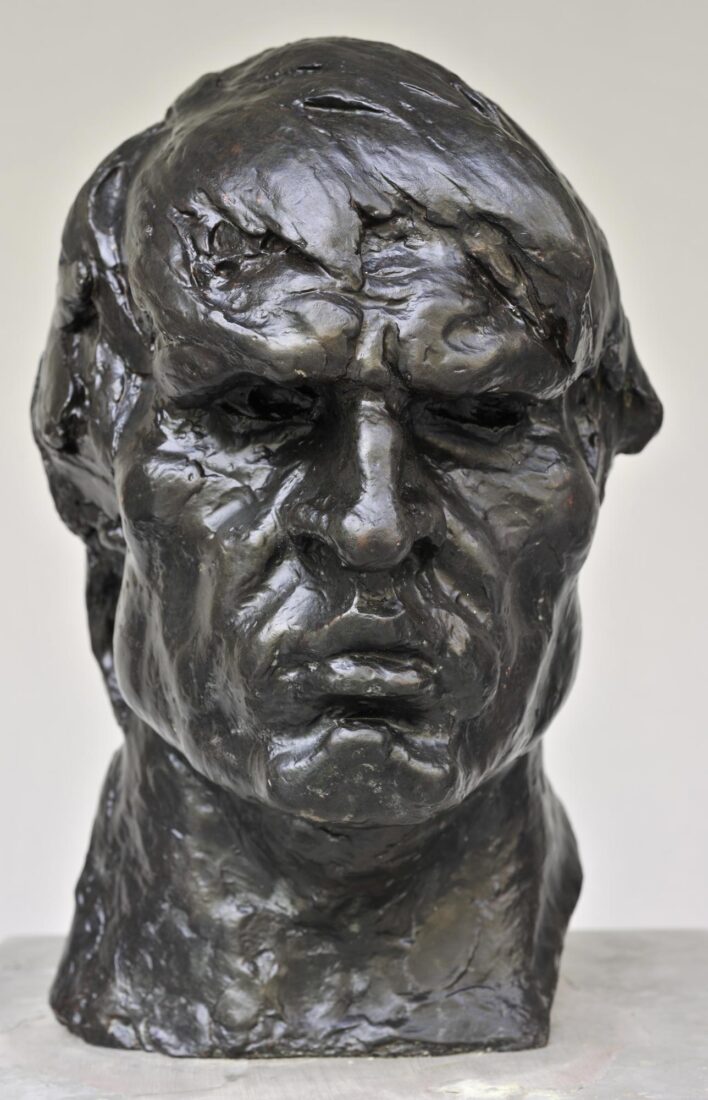

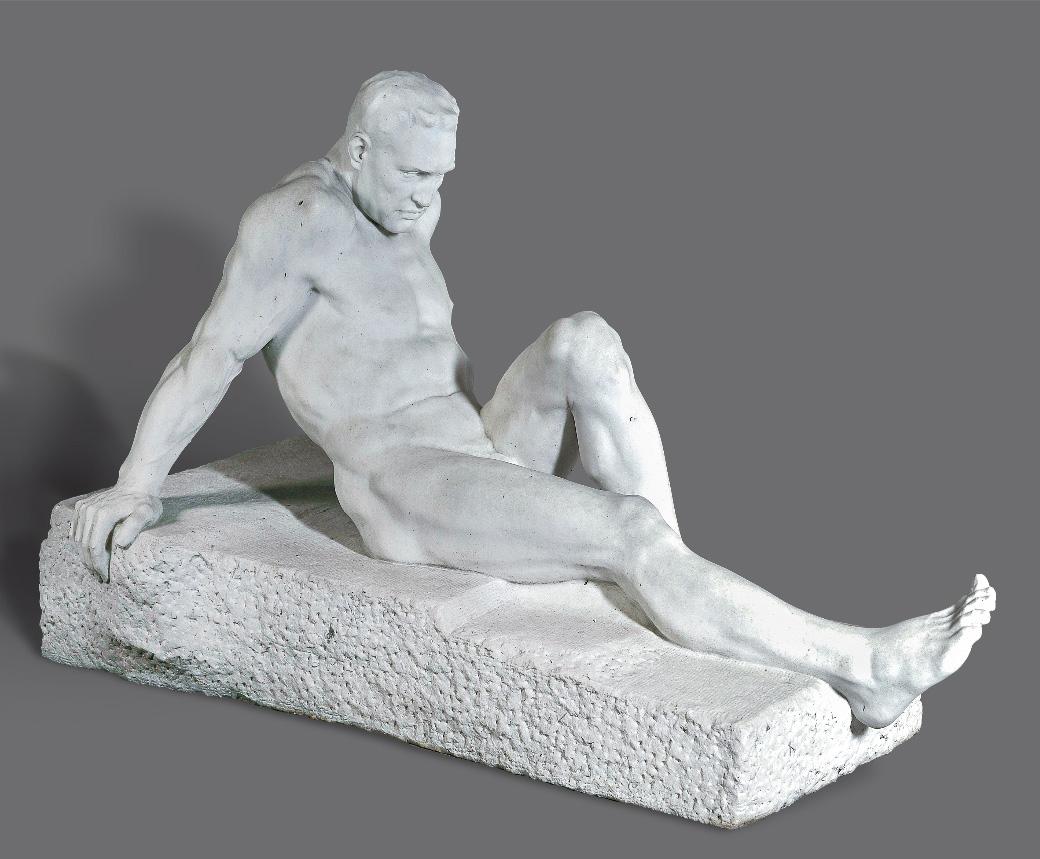

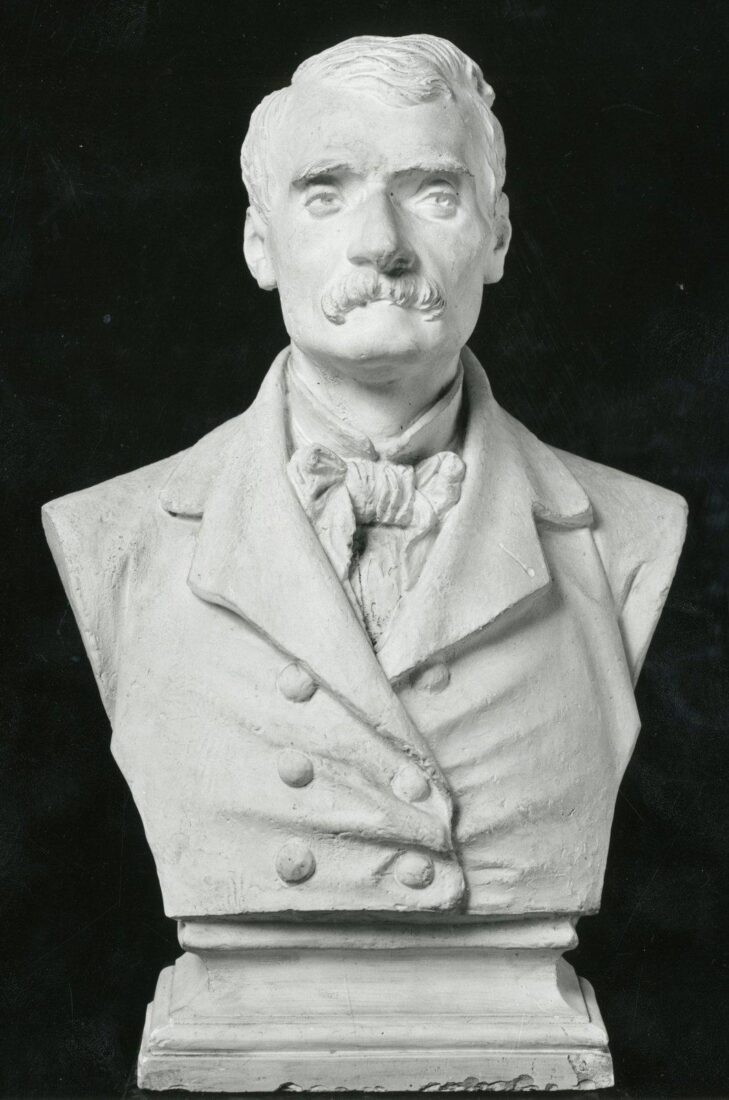

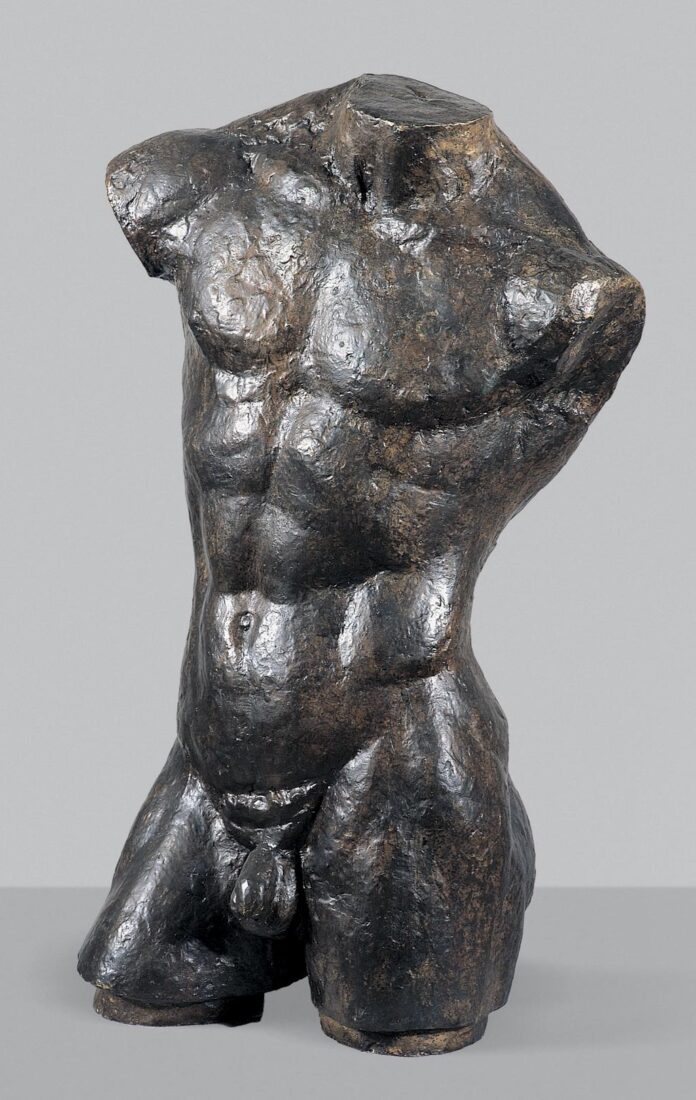

Thanassis Apartis was the first of several Greek sculptors to study under Antoine Bourdelle. The teachings of the latter and other descendents of Rodin and the simplicity of Archaic sculpture shaped Apartis’ style.

In 1921, while still a student, Apartis made the “Torso of a Portuguese Man” in a characteristic contrapposto pose, using a Portuguese aristocrat as his model. He worked on the piece for three months under Bourdelle’s close supervision and frequently productive interventions. In fact, Apartis himself considered it a milestone in his creative progress.

It should be noted, however, that Apartis did not render the “Torso of a Portuguese Man” with characteristic Archaic simplification that characterized his later work. The pulsating surfaces and fragmented treatment in this case brought him closer to the work of Rodin, whom the Greek artist admired immeasurably. Rodin was the first sculptor to intentionally produce a limbless torso as an autonomous work. In so doing, he bestowed an independent quality on the imperfect figure, stressing its expressive force through its modeling and the deliberate omission of its limbs.

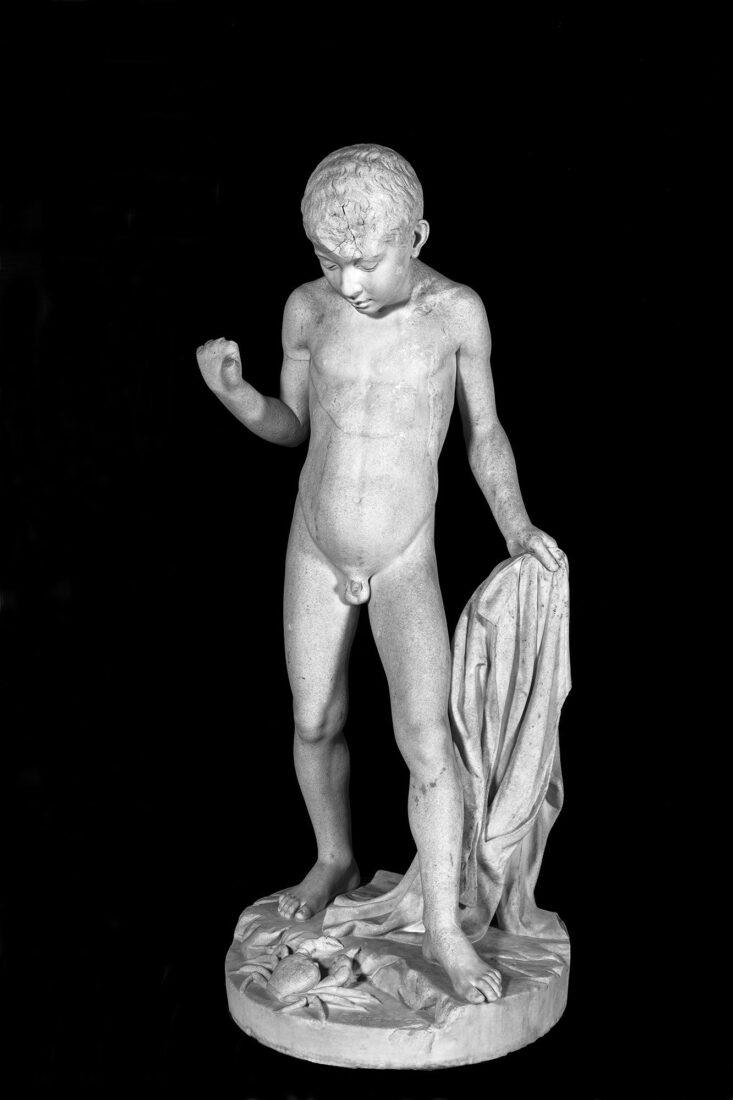

Georgios Vroutos’ “The Boy with the Crab” continues the tradition of the nude child in nature that was introduced by Dimitrios Filippotis in 1870. Vroutos was a sculptor with a genuinely classical education. At the same time, however, he was interested in compositions with realistic content, which were designed to decorate public and private gardens.

“The Boy with the Crab” combines the artist’s classical influences with a realistic rendition. The naked boy has just emerged from the sea and is holding his mantle. Terrified by the sight of the crab, he is leaning backward in an effort to strike the crab with the stone he holds in his broken right hand.

The composition is characterized by the smooth refined modeling of the childish body, the harmonious proportions and the successful adaptation of a rather rare subject as an image of daily life.