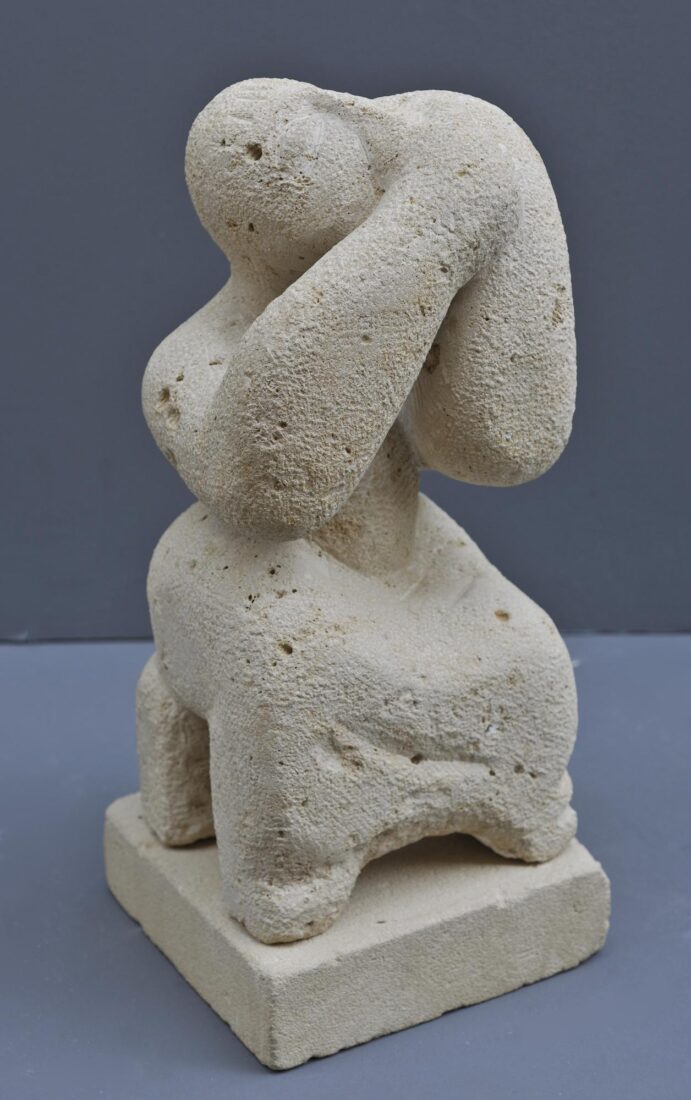

A student of Antoine Bourdelle, Bella Raftopoulou fashioned her own style combining the doctrines received from her teacher, as well as a variety of influences taken from both traditional and contemporary sources. Her favorite subjects were human figure, for the main part, as well as animals or birds, on a more limited scale, works of large dimensions, which were carved directly into stone. Initially working in a realistic manner, her style became gradually more abstract, the figures more schematic and the compositions tectonic based on geometric and organic elements and rendered with flat curved surfaces. Furthermore, the empty space in some compositions contributes to the creation of the overall impression.

The “Couple”, one of her last works, is characteristic of this point of view. Obviously inspired by the “Kiss” by Constantin Brancusi, it is built on three roughly worked pieces of stone, which are interrupted only by the empty spaces between the legs, the body and the faces of the figures. Rendered with an especially emphatic form of schematization, the two figures create the impression of complete union, while the differentiation of the female from the male body is expressed in a completely schematic way, as the middle part is curved on one side to suggest the curve of the female body.

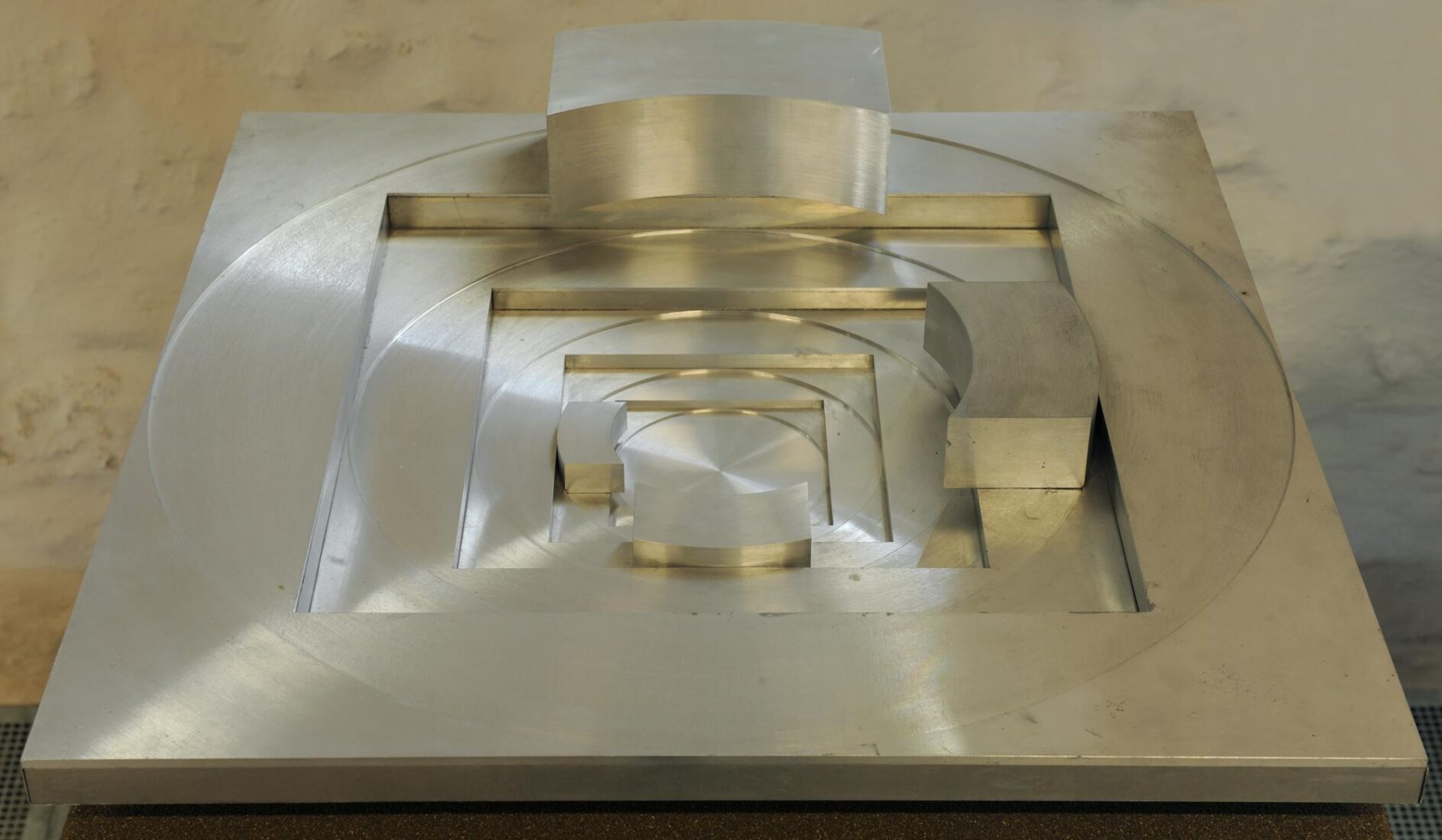

Nausika Pastra initially worked on anthropocentric compositions made of clay, plaster and bronze. Settling in Paris in 1963 she began to replace inspiration with mathematics. This turn led in 1968 to experiments with compositions in two basic geometrical shapes, the square and the circle, which then became the basis for the development of her later work. Taking these two shapes as structural forms recognized by everyone she used the methods of induction and deduction, that is, analysis and composition, and she created a new dynamic shape, which arose from the combination of the square and the circle: the “Synectron”, as she called it. This composition, for the creation of which Pastra was awarded a letters patent by the French state in 1971, is part of the series “Proportions I”, done during the period 1968-1976, and is a first study in two dimensions.

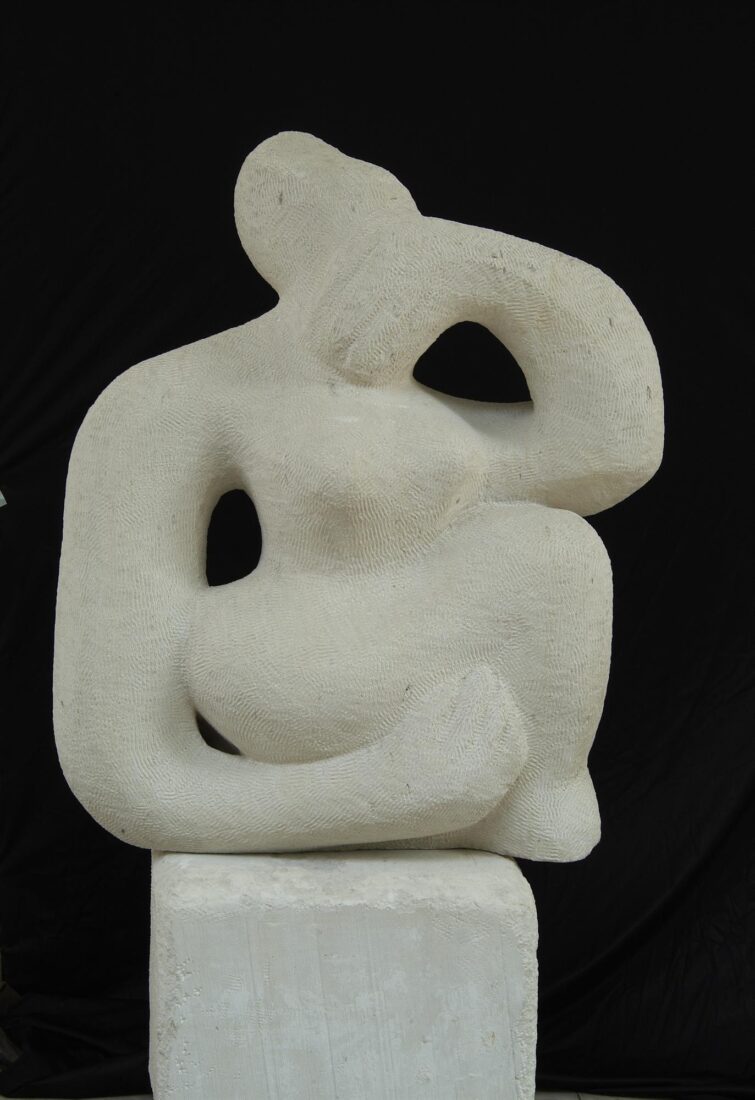

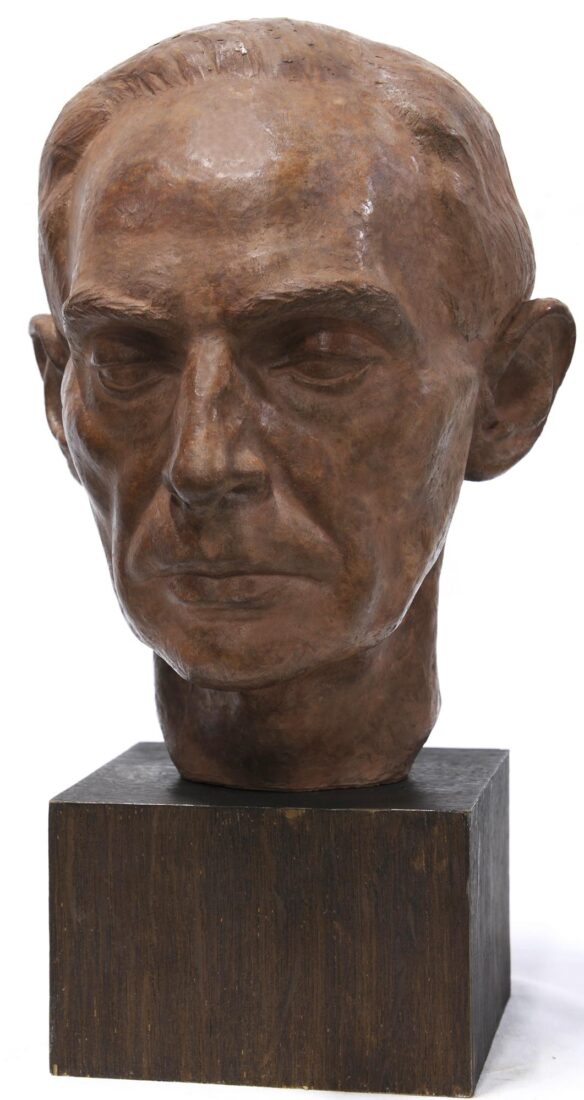

Yannis Parmakelis, cognizant of both the Greek sculptural tradition and modern trends, draws on both the past and the present for the creation of his own personal style. The human figure is what has always stirred his interest, rendered at first with realistic severity and then as an echo of the style of Henry Moore. Subsequently broadening his thematic field and introducing a drastic change in style, he has gradually turned to geometric abstraction and constructivist renderings.

“Bouquet” belongs to a period during which his forms, taken from the organic world, composed an important part of his works and is directly related to his previous work, since it belongs to the series “May Day ‘76”. This series is a continuation of “Martyrs and Victims” from the period 1969-1974, through which Parmakelis expressed his political speculation with a strongly critical eye, lifting his own artistic voice in protest over the seven years of the Greek dictatorship. “May Day ‘76”, a series with fruit-bowls full of fruit and featuring an emphatic realism, with roughly moulded May Day wreathes and bouquets of flowers formed of small spherical volumes more or less schematic, is like both a continuation and a crowning point created in order to retain in memory the sacrifice made, as well as to express, through the symbolism of those still lifes of abundance and rebirth of nature, the triumph of life.

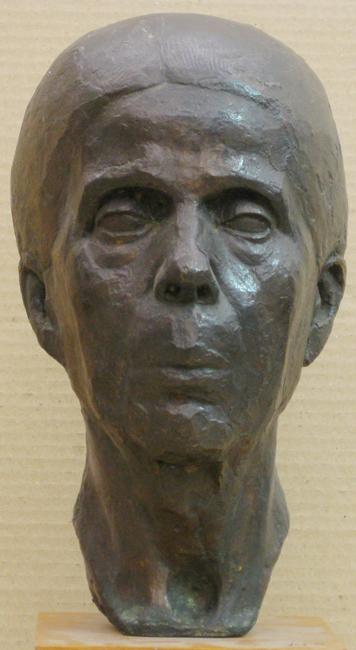

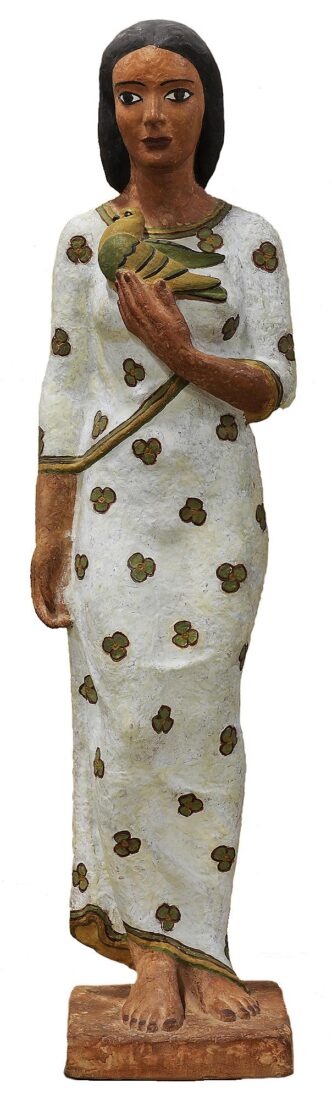

In 1918, 40 long years after the first manifestation of the symptoms of a deviating behaviour which led to the artist’s institutionalisation for 14 years, Yannoulis Chalepas’s second period as an artist began. During that time, Chalepas exhibited a totally different style: free and spontaneous, independent of academic training, guided by ancient Greek art. He now focused on the essence of each work, as he was not interested in detailed processing, refinement, or idealisation. His figures now became introverted (“St Barbara and Hermes“), solid and imposing (“Medea III“), almost hieratic at times (“Hermes, Pegasus and Aphrodite“). He gives, using spare means, the tone in the pose or facial expression and transforms his works into psychographic portraits (“St Barbara and Hermes“,“Resting female figure“,“Hermes, Pegasus and Aphrodite“). Moreover, several complementary elements, probably of an obscure symbolic meaning (“Medea III“), often add to the main theme and give a surreal tone to the work as a whole. The artist made clay models, not seeking a more finished version; he was engaged in several works at the same time. Not using an internal frame, he continued to make works inspired by the Greek antiquity and mythology (“St Barbara and Hermes“, “Hermes, Pegasus and Aphrodite“, “Medea III“), figures inspired by the urban environment, or his village (“Harvester“, “Hunter“), female nudes (“Reclining female figure“, “Small reclining female figure“), different-scale figures combined, as well as his characteristic as much as hard to interpret works (“The secret“,“ The thought“, “St Barbara and Hermes“), selecting themes suggestive of his personal experiences.

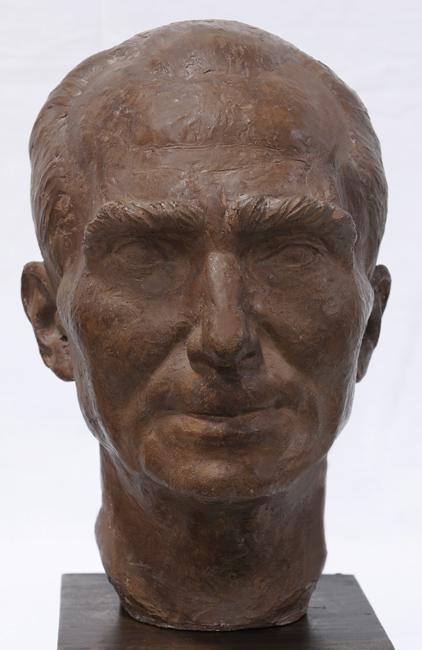

An artist faithful to the study of nature and an admirer of the art of the Renaissance, Dimitris Kalamaras always placed the focus of his sculpture on the human figure. Without ever distancing himself completely from representational imagery, he moved towards abstraction, eventually arriving at an architecturalized sculpture based on geometric volumes. This end product was the natural conclusion of his firm belief in order, harmony, symmetry and whatever had its basis in the law of numbers.

The “Head of Alexander the Great” came from a study of an equestrian statue that was to be installed in the northern city of Florina, and was part of a subject that particularly concerned him – that of the “horse and rider.” Kalamaras began researching this theme while still a student in Italy, when he measured and drew the equestrian statues of “Marcus Aurelius”, the “Colleoni“ by Andrea Verocchio and the “Gattamelata” by Donatello. The equestrian statue of Alexander (1958-1993) sums up all his concerns regarding the rendering of forms. It is a static work, imposing and rigidly frontal, built of parallelograms and cubes and based on the archetypal shape of the cross, on symmetry and on precise measurements.

Giorgos Kalakallas fashioned his personal style combining elements taken from differing stylistic trends and the tradition with the avant garde. Employing a broad thematic field, he makes use of a figurative manner for works that are commissioned and a non-figurative or a completely abstract form of expression for his own free compositions, taking advantage of the possibilities of the various materials.

“Harlequin” is an abstract composition, but at the same time retains certain characteristic elements from the traditional manner of depicting the figure of the jester. Thus, the human figure is rendered in a suggestive way, while the whole is based on dynamic curved volumes and angular geometric shapes which penetrate space, creating a composition which imposes itself, while at the same time it converses with the empty spaces which are created by the distribution of the volumes.

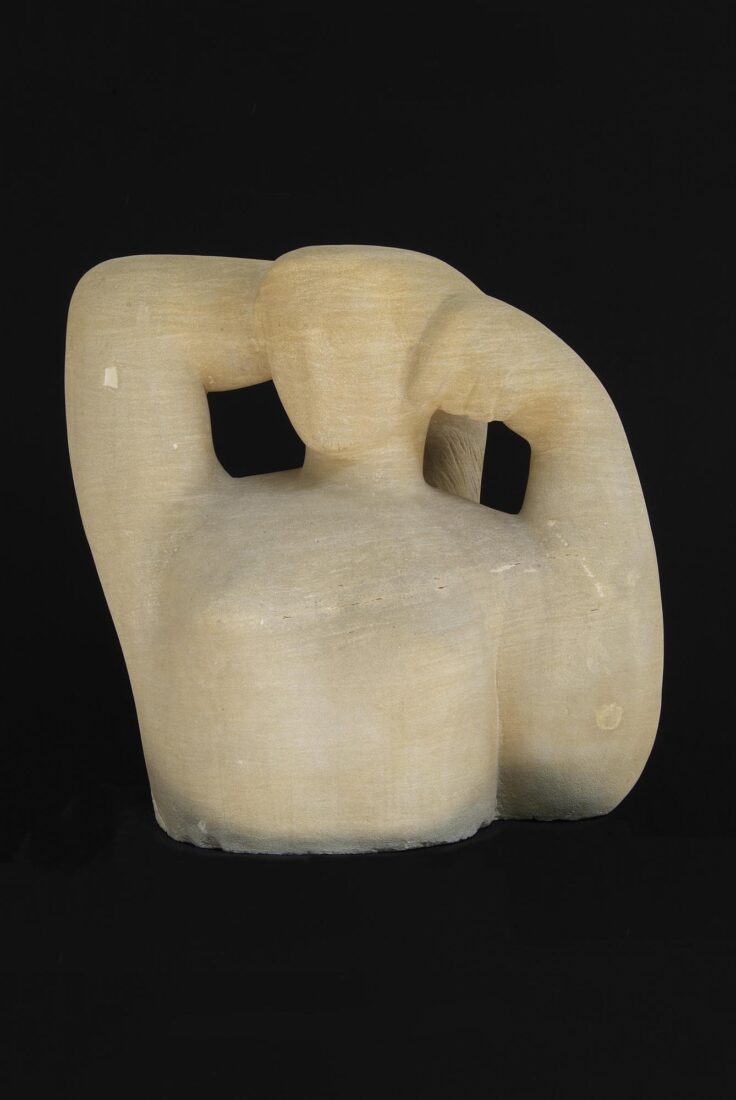

Kostas Dikefalos belongs to that very small group of sculptors who have remained faithful to carving directly on the material. Marble for the main part, and stone are the materials he has chosen in order to reveal, by carving them, biomorphic, geometric or aerodynamic forms. His compositions, very close in a number of cases to the perceptions of Constantin Brancusi concerning pure form, other times reflect the style of Henry Moore or even Barbara Hepworth, but rendered in his own personal manner, where the role of light is of the essence and indispensable for making his works distinctive.

“Spiral” comes from a broader cycle of works on the same subject carved in various kinds of marble. These works are the result of the “energy which the sphere potentially contains” and give the feeling of continual motion and evolution which is expressed through a variety of combinations, sometimes vertically arranged and delicately built and other times volumetric and compact while still other times they are slightly extended in a horizontal direction.