The son of Greek immigrants, Michael Lekakis was born and raised in New York yet maintained close ties with the Greek community.

His artistic propensity manifested itself in the late 1920s but Lekakis never had any formal training. After World War II, he began to work exclusively in wood: oak, elm, pine, rosewood, cherry and mahogany. He pruned and coaxed the trees in the garden of his Long Island studio into shapes that he later translated into artworks. Thus he combined the random and the artistic will with the process of abstraction through carving. His sculptures have titles either borrowed from classical Greek tradition or with symbolic content, but they are always Greek. The formal display of his completed work always includes a base. Frequently made out of a different type of wood, these bases are sculptures in their own right.

Lekakis’ unique relationship to his material reached its culmination in “Apotheosis”. A pine trunk supports a roughly hewn piece of elm. Three oak trees placed upside-down, their roots tangled in the air, form three imposing, motionless figures – trees, graces or dancers – their arms raised in some ritual or ecstatic dance.

Giorgos Lambrou’s first sculptures, done with wire, were an extension of his quests in drawing. During his career his forms have acquired volume, but have retained their spareness and the tendency toward the schematic, which indeed characterizes all his work. At the same time, they would come to constitute the means he uses to express his critique of the mass homogenization of contemporary society. Thus, in one of his series of compositions, to which belongs the work “Little Men Tightly Clasped III”, the focus would be on the human figure. Mass homogenization and the subsequent levelling, insecurity, alienation, and inner isolation, are expressed by means of three or more human figures which stick out of a compact volume. They are without arms or legs and, by extension, without the ability for free action or escape and end up by being identical, mere schematic suggestions of heads without any individual characteristics. The asphyxiating atmosphere is intensified by the schematization and the rhythmically repeated grooving of the surface, which creates light and dark zones and gives the impression of real bonds.

Until the late 1940s, the human figure and the figurative approach all but monopolised the attention of Greek sculptors. Nevertheless, although some remained committed to the academic approach, or to the post-Rodin French school style, others increasingly turned towards more simplified and abstract shapes, each shaping his personal style through various influences by the European avant-garde. Thus, they approached the human figure with a new perception, which led to a diversity of treatments: simplified, or completely stylised and suggestive, fragmentary, or expressionistic.

In the National Gallery collection, the work that marks the shift towards the abstracted, allusive rendition of the human figure, in what is in fact one of the most “extreme” examples, while also ushering in the 1950s, is “Two Girls” by Lazaros Lameras. Reminiscent of Cycladic figurines, the two girls are upright, stylised and almost two-dimensional, retaining only the basic elements of female body forms, reaching the limits of abstraction.

Centered on the human being, Kostas Klouvatos started out with a realistic but simplified rendering of his figure and then became gradually more non-figurative till he achieved nearly completely abstract shapes. Inspired by the figurines from the geometric period or folk art, he aspires to express everyday human situations, passions, problems and struggles, in the framework of social speculation.

The work exhibited at the National Glyptotheque belongs to a series of compositions from the Sixties which aspire to project the essence of the content, adopting an expressionistic style. This tendency is obvious both in the manner of rendering the figures and in the manipulation of the surface of the material which the sculptor deliberately leaves rough and unworked, so that it creates the impression of rust, giving even greater intensity to his compositions’ content.

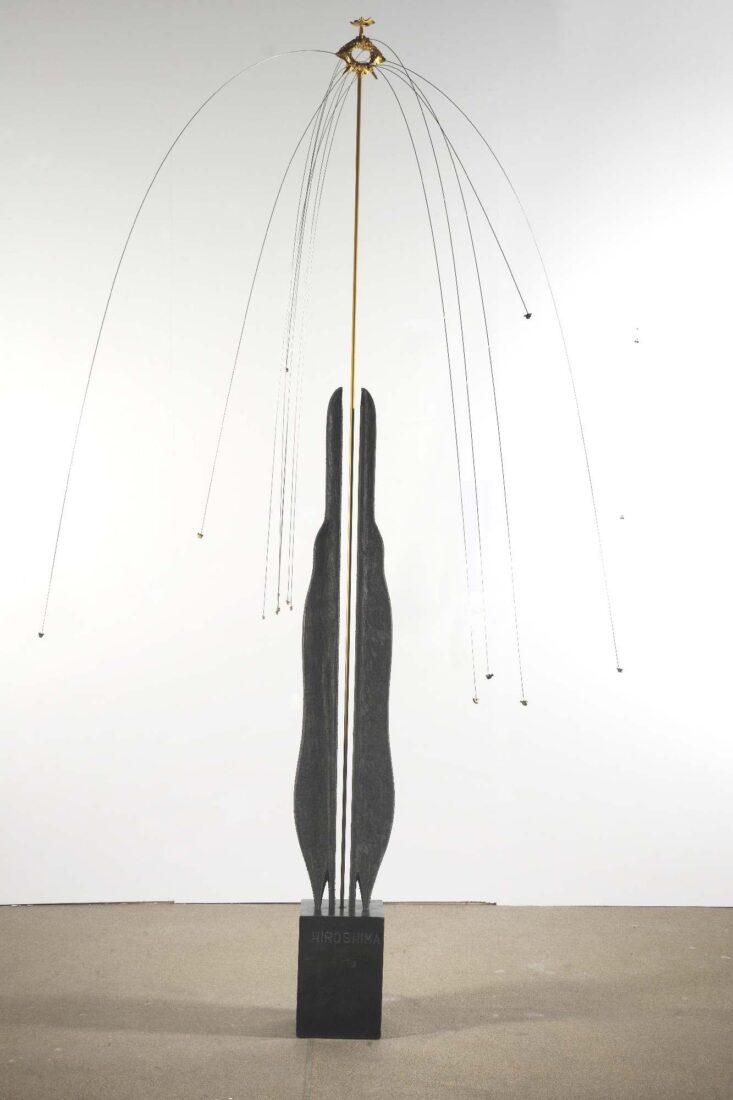

Spyros Katapodis was a sculptor concerned with the human figure, since his subjects always revolved around the human being or referred symbolically to situations related to human life. With a tendency toward abstraction, he worked with elements from cubism, constructivism and even surrealism, giving form in his compositions to whatever moved him or made him dream.

Two of the most common subjects he addressed in his sculpture, the chair and the human figure, are combined in “Aretoussa”. The stressed, compact, but concise rendering of volume of the girl’s body, who appears to be set like a doll on the chair, is in contrast to the finely-made chair, a recollection of older furniture, which takes the form of a swing as the back frames the body of the child. The composition is unquestionably emotionally charged, perhaps by the childhood or adolescent experiences of the artist, something true of quite a number of his works, thus revealing nostalgia for the innocence of childhood.

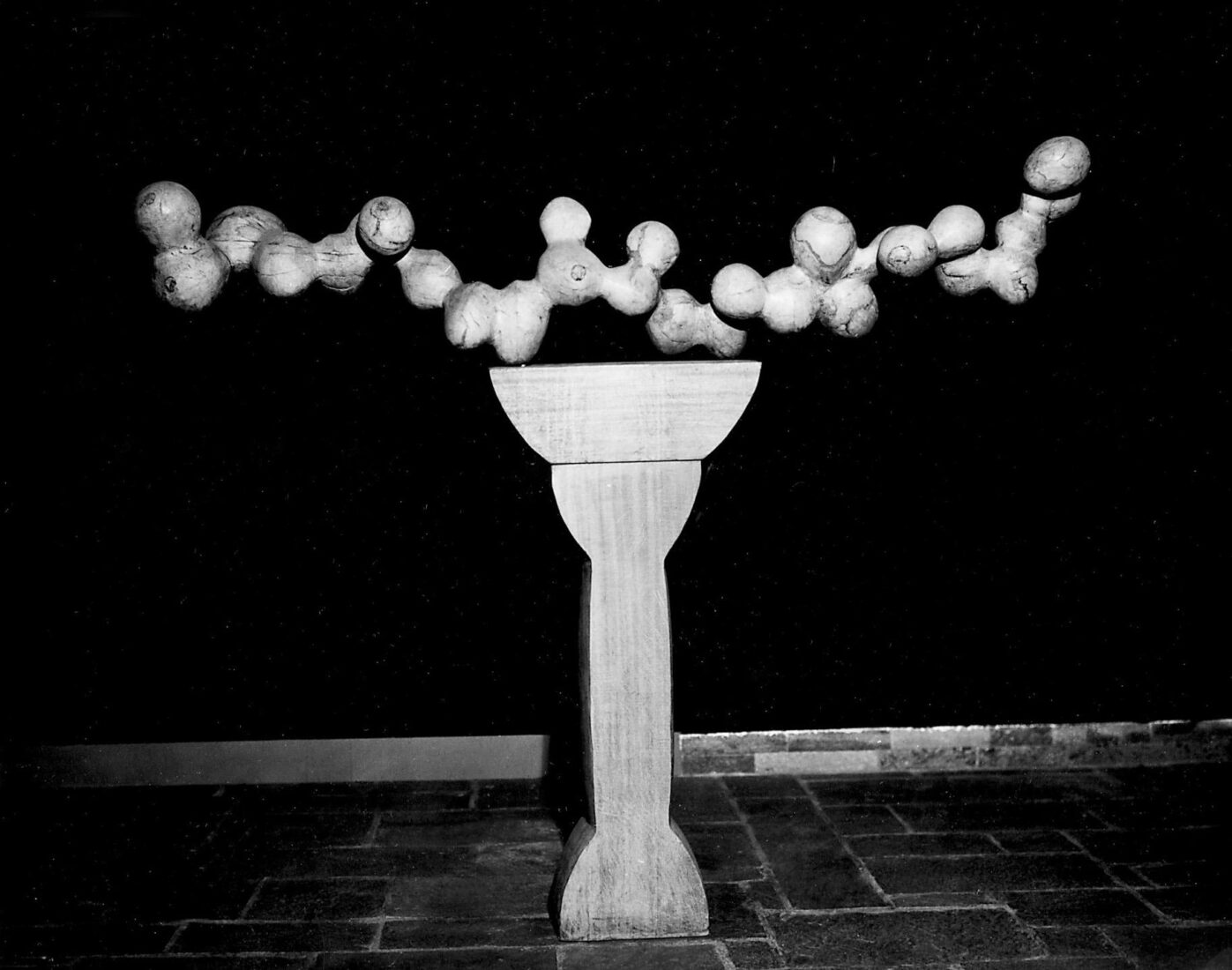

Dimitris Konstantinou has always expressed himself primarily through geometric or organic abstraction. Starting in the early 1970s he created Op Art-type geometric compositions. He then went on to use the cube and circle as basic modules in a constructivist style. In this series, equilibrium and the introduction of the void play an important role. The cube opens up and breaks down in smaller shapes that may also be reassembled. Sometimes they become autonomous constructions that have been generated by the original cube. In the same vein but using the curve as the basic structural element, the transformations of the compositions with cubes were then converted into transformations of circular shapes. These circular shapes intersect each other, intertwine, twist around each other, or are born of one another.

“Genesis” is a characteristic work in which the void enters the composition and plays an essential part in creating the final aesthetic effect.

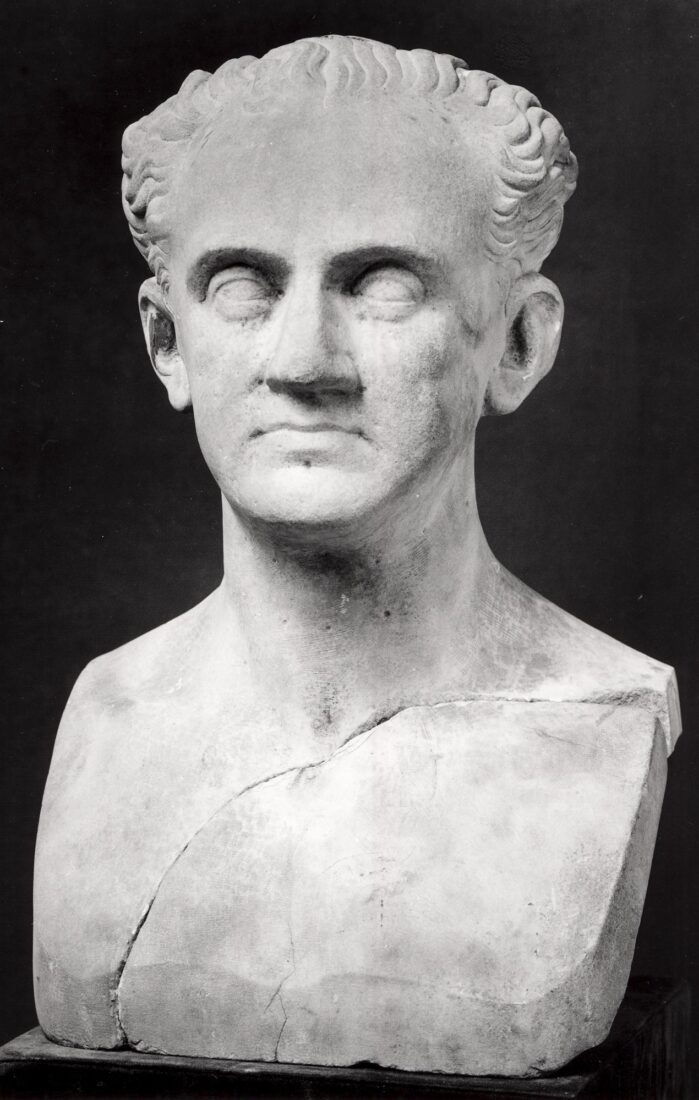

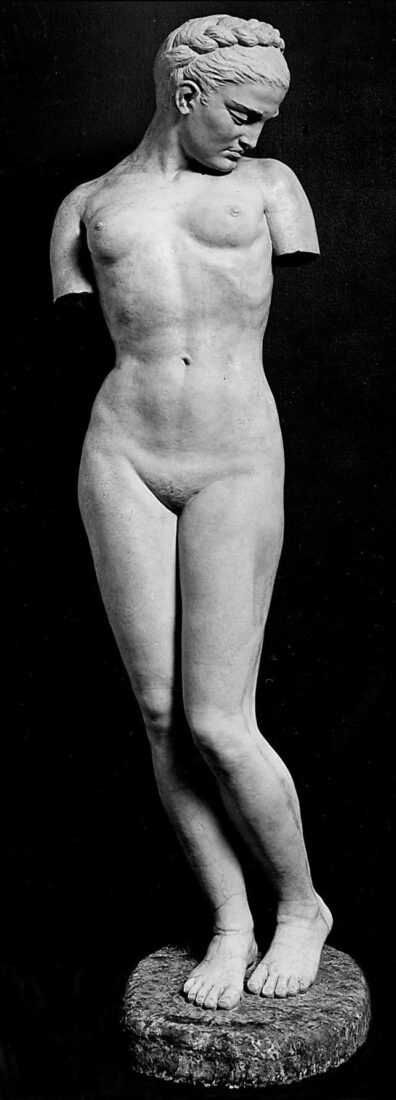

Student of Antoine Bourdelle, Georgios Kastriotis remained faithful to an “anthropocentrically” focused depiction. Though from his teacher he retained the doctrines regarding the rendering of surfaces, the clarity of drawing and the love of impulsive movement, during his career he formed his own particular style which combined realistic rendering with symbolism, or even allegory.

“Modesty” is part of a thematic cycle, where the nude or semi-nude female figures function as symbols or allegories. The young woman with the finely-drawn body and whose head is turned left and lowered with a bashful glance, produces the type of virginal beauty which stirred the artist‘s interest in quite a number of cases. Her arms severed high above the elbows reveal at the same time a tendency to associate this sculpture with the beauty of ancient statues and the fragmentary figure, which Rodin first made into an independent work of art.

Kostas Koulentianos is one of the most important and consistent representatives of abstraction in Greek sculpture. He studied at the Athens School of Fine Arts, leaving in 1945 for Paris with the first postwar group of artists on scholarship from the French government. From then on, France became his permanent place of residence until his death.

In 1947 he met Henri Laurens, an acquaintanceship that proved crucial to his work. Koulentianos then abandoned traditional materials and began working in lead and iron. His work in the early fifties was still representational, but with a definite abstract leaning. In 1954 he moved into the realm of total abstraction. He was moved by the qualities of iron, steel and the rods used to reinforce concrete. In the sixties his sculptures became geometric in form, penetrating dynamically into the space with an upward thrust that was intensified by sharp vertical endings.

In the seventies he continued to construct sculptures that had a dynamic spatial presence. At that time, however, he used large, flat or curved iron bands, painted and screwed together. These metal bands extend out in various directions. “Abstract” falls into this category of works. It stands solidly on the ground while at the same time extends horizontally and vertically, creating the impression of a latent upward movement, like a bird about to take flight.

Kostas Koulentianos was one of the most important representatives of abstraction in Greek sculpture. After completing his studies at the Athens School of Fine Arts, he left for Paris in 1945 as part of the first post-war group of scholarship artists funded by the French government. France then became his permanent place of residence until his death.

His meeting with Henri Laurens in 1947 was definitive for his artistic career and contributed even more to the rejection of the academic precepts he had been taught but which he had already begun to doubt. At the same time he abandoned the traditional materials, clay, plaster and bronze, and turned to lead and, later, iron. The influence of Laurens can be easily spotted in the works from the Fifties, in which Koulentianos was still working in a figurative framework, but with a strong abstractive tendency, his subjects still revolving around the human figure. In these works, such as the “Sea Victory”, curved organic forms are the rule, along with the movement and succession of empty and full spaces which reveal from early on the artist’s consistent speculations in regards with space, light and volume.