Nikos Perantinos remained faithful to an anthropocentrically conceived depiction, in agreement with the classicist perception, during a period in Greece when quite a number of artists had begun to turn to non-figurative or even completely abstract shapes. Busts and full-bodied statues, whether from free inspiration or commissions, made up the largest part of his artistic work.

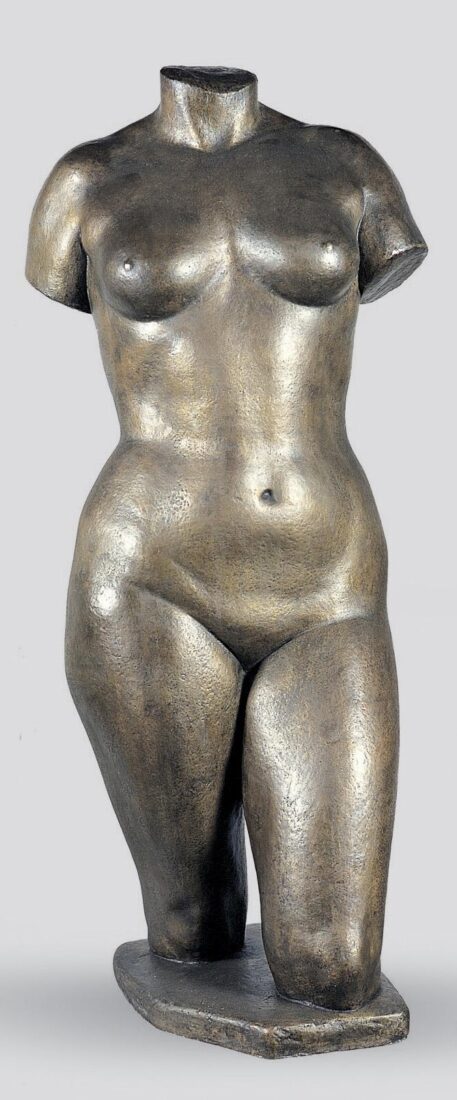

“Torso”, which is based on his wife, Olympia, is part of a series of works, starting in 1938 with “Olympia”, where the torso is shown with the head. In 1939 the plaster model was made of the work at the National Glyptotheque. In subsequent versions, the main theme is sometimes retained untouched and other times becomes part of a statue, full-bodied or not, with or without a head and limbs and with small variations in the manner of moulding, arriving at the final full rendition in 1960.

The vigorous female body, imposed on space with her dynamic presence, the clear contours and the harmonious moulding, refers back to a sculptural perception of form as it is expressed in the works of Aristide Maillol and reveals the idealistic outlook that more generally distinguishes Perantinos’ sculpture.

Aspassia Papadoperaki is a sculptor focused on the human figure. Although she did not reject figurative represantation, she adopted strong schematization based on geometric shapes. Also a student, among others, of Dimitris Kalamaras, she followed her teacher’s precepts on order, harmony, measure and whatever was based on the law of number, creating tectonic compositions formed of geometric shapes. The views of Le Corbusier pricked her interest as well and expanded her already active speculations, leading her to further examine and study the figure in regard to measure and proportion.

“Couple with Horse” is a composition which expresses clearly the sculptor’s principles in regard to the rendering of forms which arise from careful calculation and measurement and is based on geometric shapes.

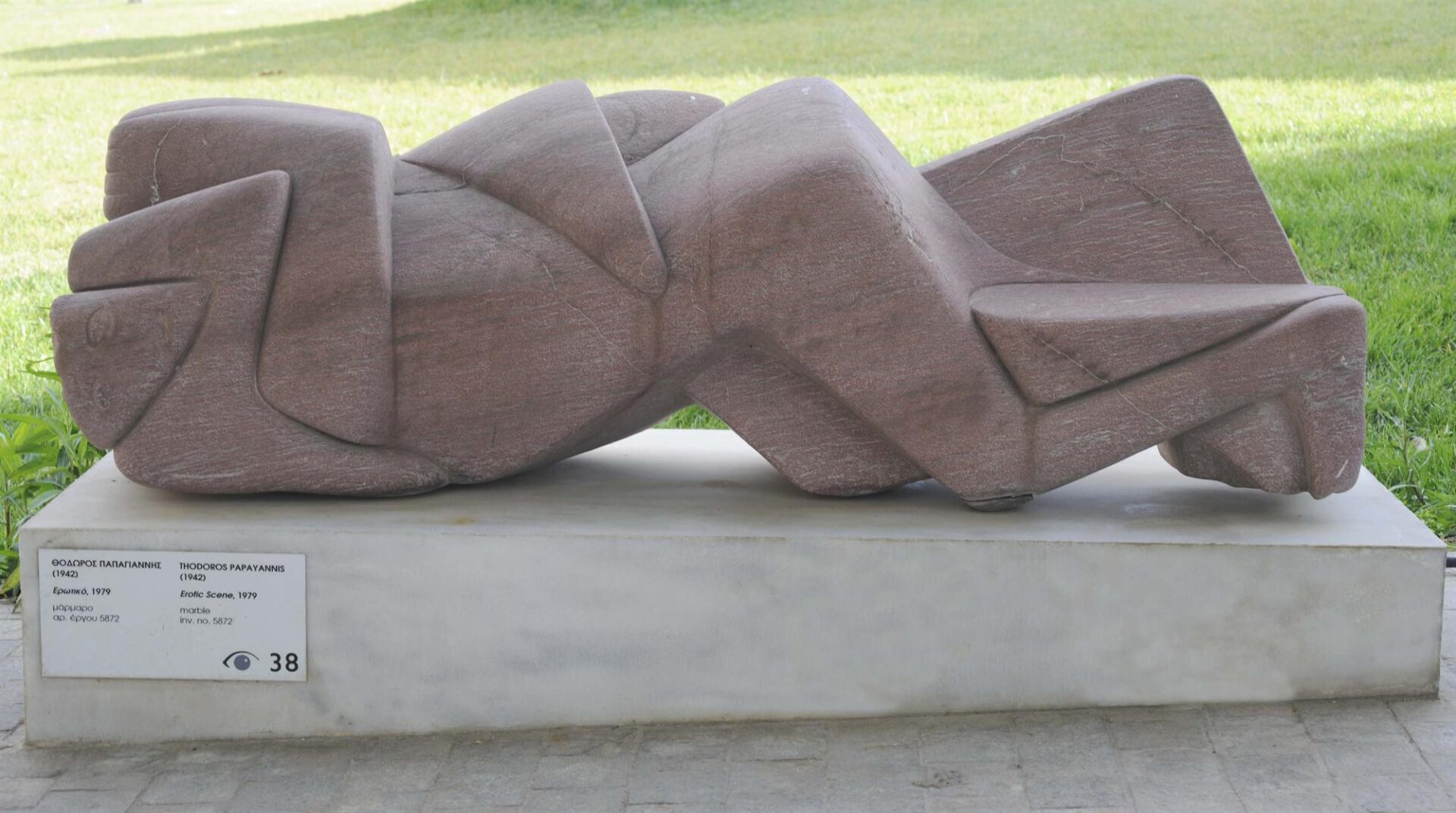

Thodoros Papayannis made the human figure practically his exclusive subject, but liberated from any trite naturalistic stylization. His knowledge of ancient Greek civilization and the broader Mediterranean region, Greek folk tradition and his post-graduate studies in Paris later on, nourished, by the stimuli they offered him, the formation of his style.

The image of the couple, in a standing or seated pose, but locked in an erotic embrace as well, was from early on one of his particularly favored subjects for sculpture. The erotic embrace was the spark for the creation of a series of compositions such as “Erotic Scene”, where the figures of the couple are entangled and thus tectonic compositions are created, formed of geometric volumes. These compositions echo the cubist sculpture of Henri Laurens, Ossip Zadkine and Jacques Lipschitz while at the same time borrowing elements from images of nature taken from old memories: “…I often recognize in my erotic compositions specific landscapes from the volumes of the mountains I drew at one time…I see the female body being transformed into an adventure, beckoning collection of hills and valleys…” he characteristically writes, describing his work.

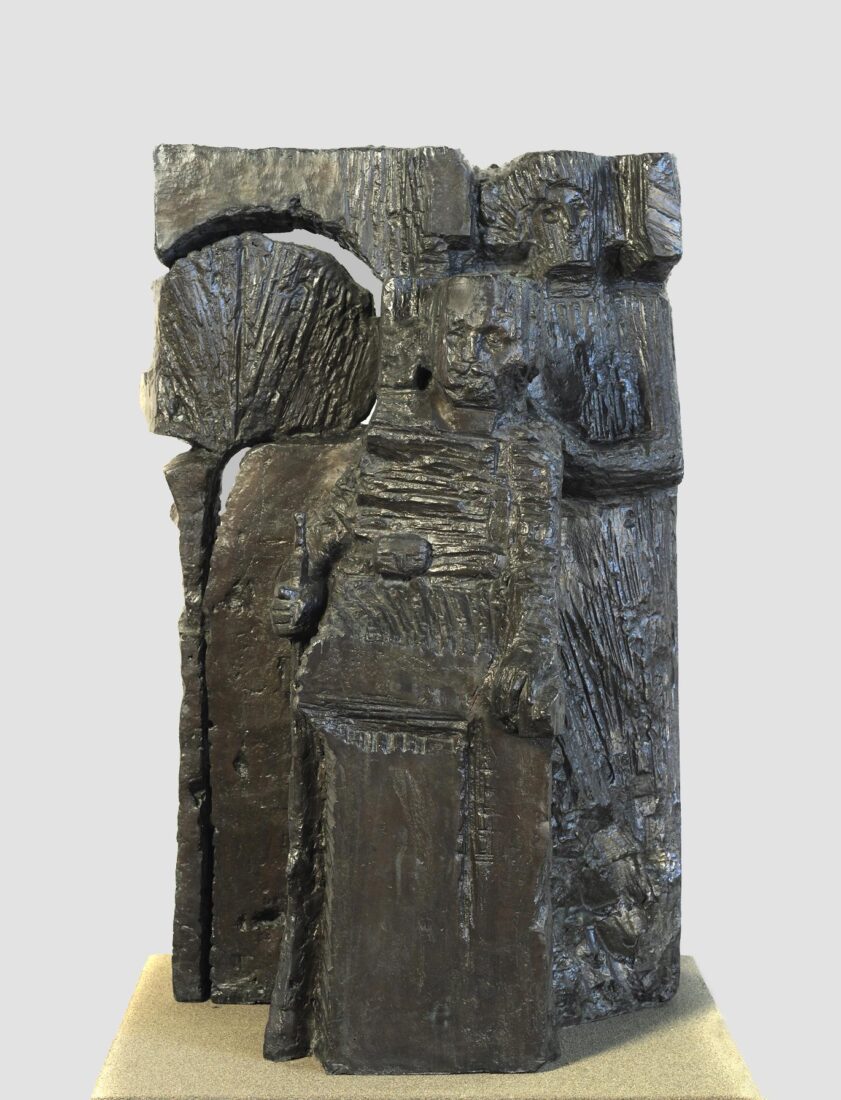

The work of Thymios Panourgias revolves around the human figure, sometimes left free in space and other times incorporated into a schematic background which suggests a natural landscape. Conversant with the traditional manner of depiction, but also contemporary trends, he works with stone, marble and metal and creates, among others, abstract compositions made of compact and heavy geometric volumes with a roughly worked surface.

The “Composition” is a characteristic work in which the seated man and the standing woman project outward in a high relief from the compact rectangular volume which surrounds them and constitutes the background of the composition. This background, which makes up a schematic suggestion of a landscape with a tree, sets off the space and creates a specific environment, in which the two figures are incorporated.

The human being – as form or idea – is the focus of Vangelis Moustakas’ sculpture. His subjects, inspired by Greek mythology, Greek or ecumenical reality, as well as his own personal experiences, is a protest against pain, violence and oppression. Ancient Greek models are combined with the trends found in modern art – fragmentation, non-figurative rendition, surrealistic atmosphere – while the light traverses the surfaces by means of alternations of the empty and full spaces of the composition.

The subject of “Nike” (“Victory”) has repeatedly occupied him, as a triumphal response of the human being to pain and death. The “Victory” exhibited at the National Glyptotheque is a composition with five fragmentary figures, with the figure of Nike commanding the right side. Freely exploiting the ancient prototype of the “Nike of Paionios”, it was made in 1967 in recollection of a specific historical event: the victory of the Israelis in the Six Day War of June 1967. For Vangelis Moustakas this event had a particular resonance, as he considers the Jewish people to embody par excellence the pain and tribulation suffered by all humankind. So this Victory expresses the end of centuries of terror.

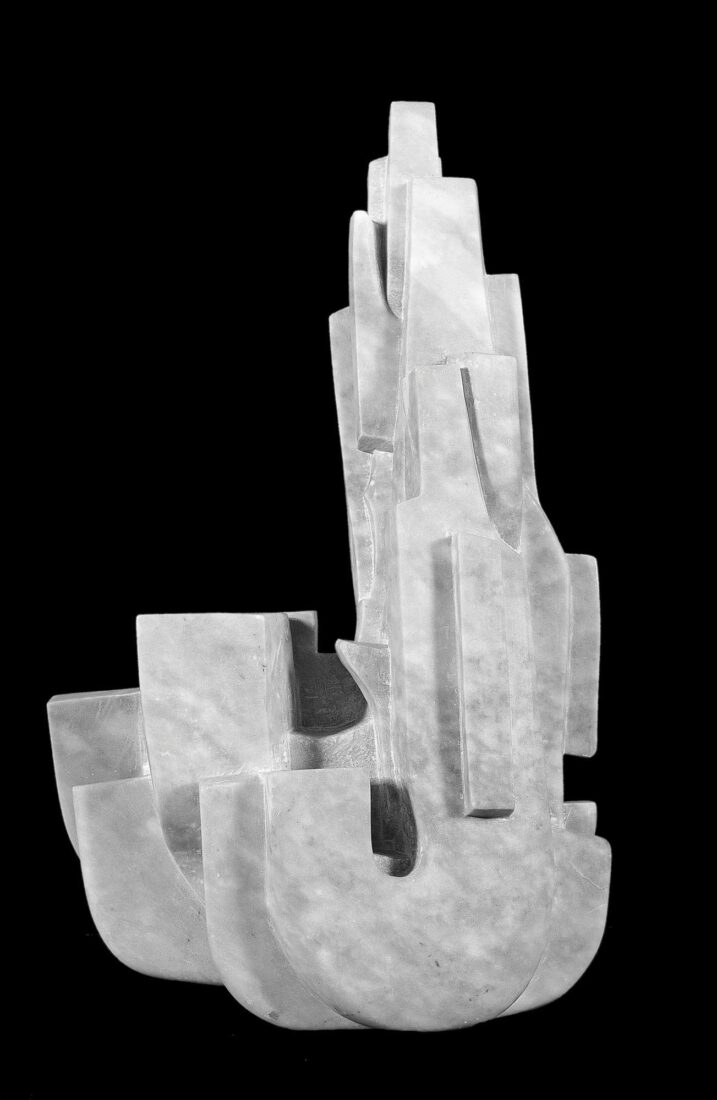

The sculpture of Giorgos Megoulas contains compositions both from the field of figurative art, mainly commissions, and abstraction, the outcome of free inspiration and personal quests. These quests are particularly concerned with time, space, light and the possibilities offered for the projection of compositions, as well as the recording of movement.

In “Saxophone” the fragmented volumes of marble, which form successive levels, render schematically but clearly the musical instrument, calling on the viewer to watch the imaginary execution of a musical composition and the alternation of movement in the flow of time, while at the same time permitting the light to traverse the surfaces creating shadows and illuminations which put the materials’ texture forward.

Klearchos Loukopoulos was one of the most important representatives of non-figurative sculpture in Greece. He started with realistic depiction, during the years between the wars, but soon turned toward more abstract forms, guided by archaic sculpture. 1955-1960 was a transitional period for him since he abandoned the use of stone and marble and turned to iron, making compositions on the border between the figurative and the abstract, inspired by Mycenean art. His steady course toward complete abstraction reached its peak at the beginning of the Sixties when he abandoned representational work once and for all. The artist’s constant quest for new expressive methods led him to compositions based on assemblage of chance materials made of iron, while after 1970 his works acquired a constructivist character. “Superimposition” comes from that period and is the continuation of a series of compositions based on polyhedric volumes scattered in space, or assembled rhythmically in constructivist constructions, with a strong sense of balance and a latent motion which arises from the assemblage of the separate elements.

Alex Mylona’s tendency toward an abstract rendering and her acquaintance with important artists from the European avant-garde played a decisive role in the formation of her personal style. The preoccupation with volume and the contribution of space to sculptural depiction led her at the end of the Fifties to the formulation of a series of works rendered with the greatest possible schematization, in which the third dimension is abolished. Her perceptions regarding the function of sculpture in relationship to the human being and the everyday environment, led her in the middle of the Seventies to the creation of non-figurative compositions made with sheets of zinc or stainless steel, based on rounded shapes. Some of these compositions, which in reality are maquettes for architectural constructions, can at the same time constitute objects of everyday use.

The maquette for “Development of the Circle”, a composition which combines intersecting, horizontal and vertically placed sections of circles and broad two-dimensional surfaces, belongs to this series and constitutes the sculptor’s proposal for a seat in a museum, which was transferred into large dimensions in iron and is exhibited at the National Glyptotheque.

Father of the painter Nikephoros Lytras, Chatziantonis Lytras was a folk marble-cutter.

In the relief depiction shown here, a scene from the everyday life of the Greek countryside is illustrated. The windmill occupies nearly the entire center of the depiction and is framed by a schematically rendered palm tree and a young island woman, who is drawing near the stairs, laden with a sack of wheat. The folk elements are expressed through a flat perspectiveless rendering, a lack of proportions, and the rendering of the young woman, her face shown in three-quarters profile while the rest of her body is in full profile, just as one finds in folk painting. A cross placed high up, in the center of the marble frame, symbolizes divine assistance.

The work, direct, simple and spontaneous, constitutes a characteristic example of folk technique in marble-carving, done just before the appearance of official sculpture in the New Greek state.

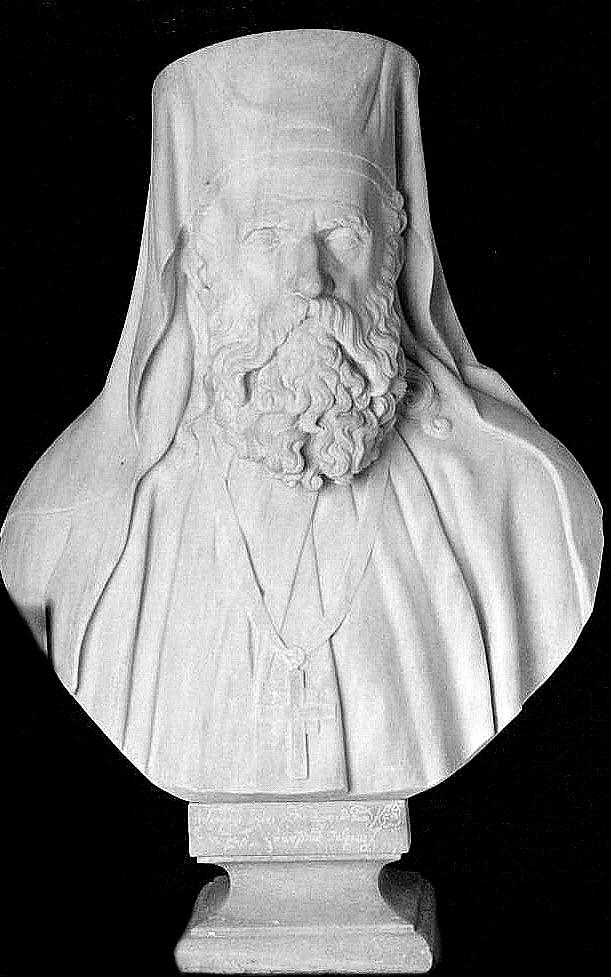

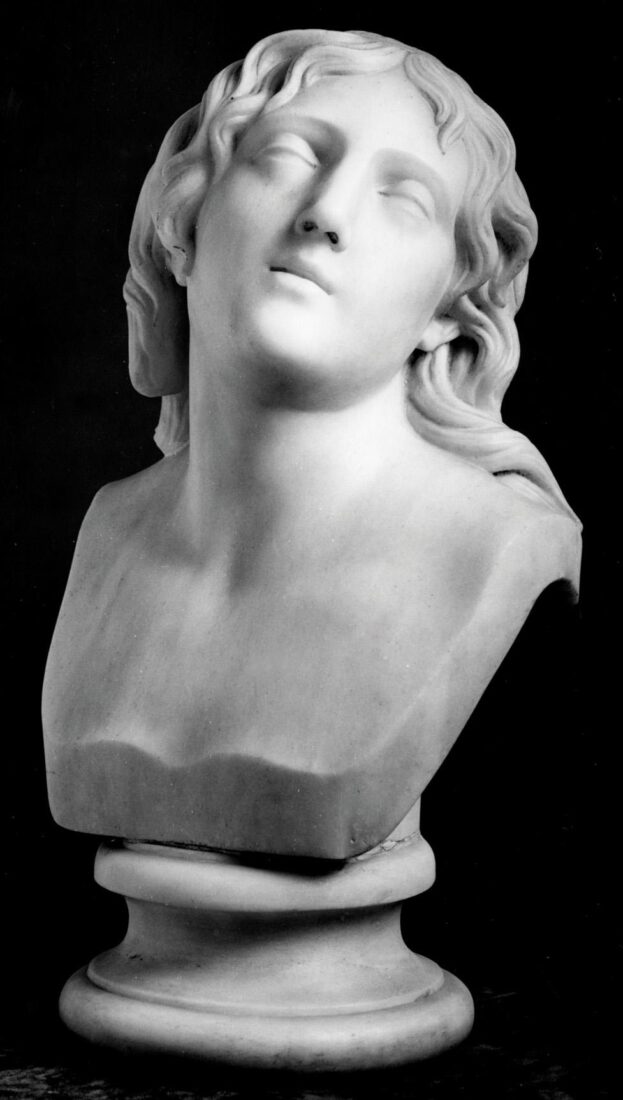

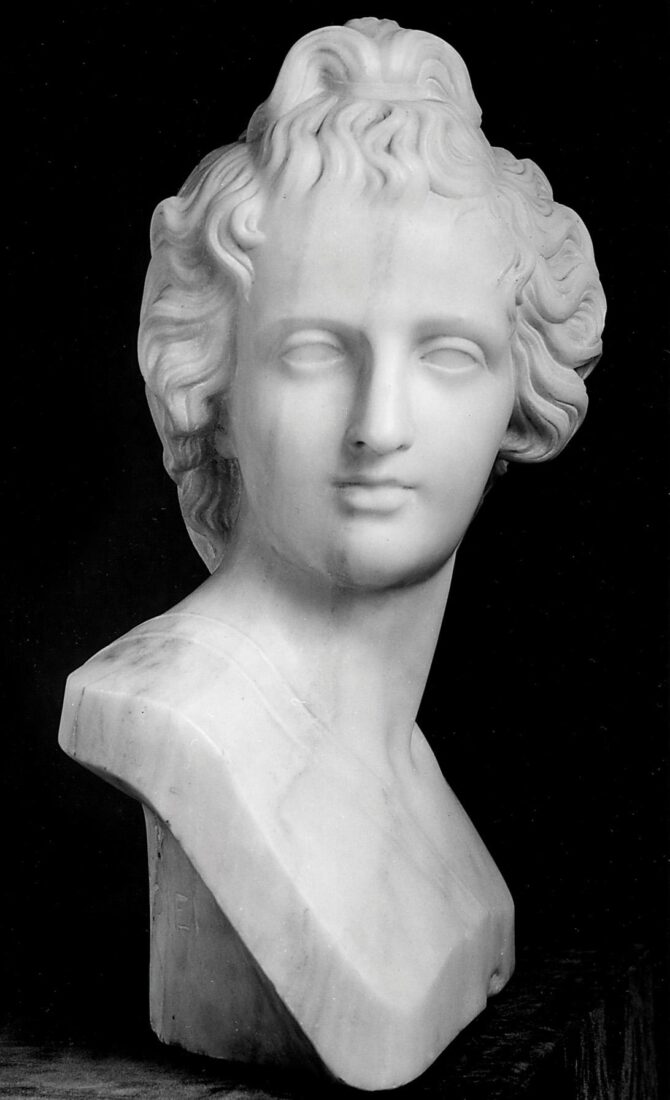

Ioannis Kossos was one of the first modern Greek sculptors to graduate from the Athens School of Arts and fashioned his style in the neoclassicist spirit that the German sculptor Christian Siegel brought to Greece. His subject matter included busts, statues, funerary monuments and allegorical compositions, or inspired by antiquity. To this last category belong the two youthful figures that symbolize Eros and Psyche, carrying on the tradition that started in antiquity and reappeared in European neoclassicist sculpture.

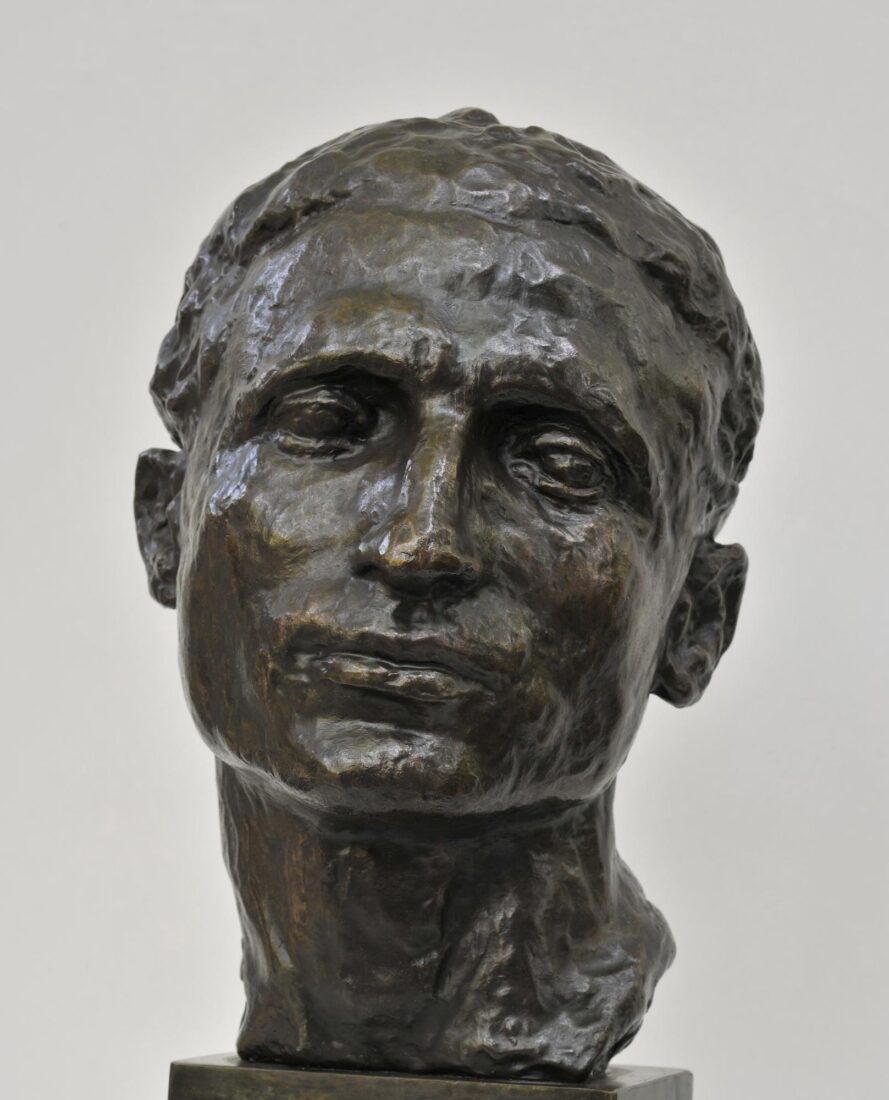

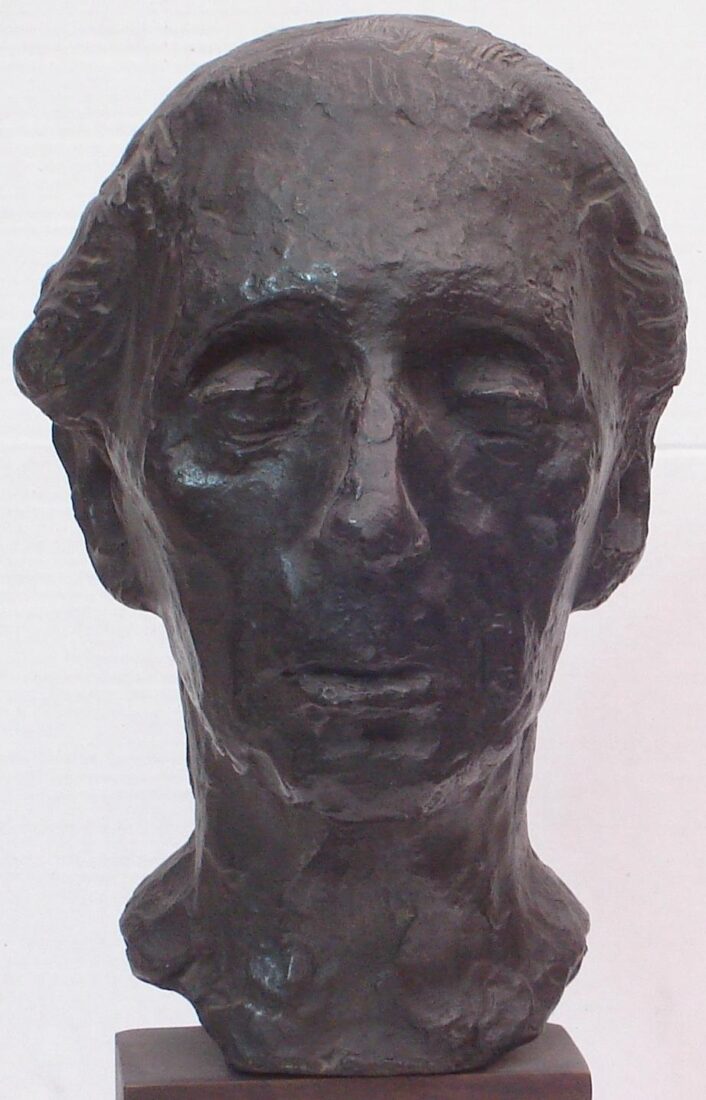

For the rendering of this subject, Kossos elected to carve two separate heads which could stand on their own as autonomous works, while at the same time they had a direct connection to each other and where the one supplemented the other. “Eros” is presented as being somewhere between an adolescent and a man, with an expression proud and self-confident, his lips half-open and his head turned to the left, toward “Psyche”. “Psyche” is presented in the form of a young woman, her head pulled back voluptuously, surrendering to the charms of Eros.

The rendering of these two figures is done according to the neoclassicist tradition, with the consequent affectation in pose and expression, the nudity of the bodies and the soft and smooth framing of the surfaces, without fluctuations, and emphasis on details.

Ioannis Kossos was one of the first modern Greek sculptors to graduate from the Athens School of Arts and fashioned his style in the neoclassicist spirit that the German sculptor Christian Siegel brought to Greece. His subject matter included busts, statues, funerary monuments and allegorical compositions, or inspired by antiquity. To this last category belong the two youthful figures that symbolize Eros and Psyche, carrying on the tradition that started in antiquity and reappeared in European neoclassicist sculpture.

For the rendering of this subject, Kossos elected to carve two separate heads which could stand on their own as autonomous works, while at the same time they had a direct connection to each other and where the one supplemented the other. “Eros” is presented as being somewhere between an adolescent and a man, with an expression proud and self-confident, his lips half-open and his head turned to the left, toward “Psyche”. “Psyche” is presented in the form of a young woman, her head pulled back voluptuously, surrendering to the charms of Eros.

The rendering of these two figures is done according to the neoclassicist tradition, with the consequent affectation in pose and expression, the nudity of the bodies and the soft and smooth framing of the surfaces, without fluctuations, and emphasis on details.