The zenith that Greek sculpture achieved in antiquity lost ground with the coming of Christianity. Christianity rejected every feature that came from the idolatrous world, thus relegating sculpture to a secondary, decorative role. In post-Byzantine times and until the early 19th century, sculpture survived in folk art, woodcarving, metal work and stone carving.

Fanlights are a distinct category of stone carving and are encountered primarily in the Cycladic Islands. They are semicircular with perforations and relief designs, and are placed over windows and doors, covering the load-bearing triangular openings, and have multiple functions: practical, because they allow light into the interior; aesthetic, because they have ornamental images; and even magical, because the designs are frequently of a talismanic or apotropaic nature.

The imagery used to decorate fanlights includes religious and human figures, animals, birds and plant motifs, geometric shapes, buildings and ships. Stylistically, they are a combination of elements from the West, the East and folk tradition.

The zenith that Greek sculpture achieved in antiquity lost ground with the coming of Christianity. Christianity rejected every feature that came from the idolatrous world, thus relegating sculpture to a secondary, decorative role. In post-Byzantine times and until the early 19th century, sculpture survived in folk art, woodcarving, metal work and stone carving.

Fanlights are a distinct category of stone carving and are encountered primarily in the Cycladic Islands. They are semicircular with perforations and relief designs, and are placed over windows and doors, covering the load-bearing triangular openings, and have multiple functions: practical, because they allow light into the interior; aesthetic, because they have ornamental images; and even magical, because the designs are frequently of a talismanic or apotropaic nature.

The imagery used to decorate fanlights includes religious and human figures, animals, birds, plant motifs, geometric shapes, buildings and ships. Stylistically, they are a combination of elements from the West, the East and folk tradition.

The zenith that Greek sculpture achieved in antiquity lost ground with the coming of Christianity. Christianity rejected every feature that came from the idolatrous world, thus relegating sculpture to a secondary, decorative role. In post-Byzantine times and until the early 19th century, sculpture survived in folk art, woodcarving, metal work and stone carving.

Fanlights are a distinct category of stone carving and are encountered primarily in the Cycladic Islands. They are semicircular with perforations and relief designs, and are placed over windows and doors, covering the load-bearing triangular openings, and have multiple functions: practical, because they allow light into the interior; aesthetic, because they have ornamental images; and even magical, because the designs are frequently of a talismanic or apotropaic nature.

The imagery used to decorate fanlights includes religious and human figures, animals, birds, plant motifs, geometric shapes, buildings and ships. Stylistically, they are a combination of elements from the West, the East and folk tradition.

The zenith that Greek sculpture achieved in antiquity lost ground with the coming of Christianity. Christianity rejected every feature that came from the idolatrous world, thus relegating sculpture to a secondary, decorative role. In post-Byzantine times and until the early 19th century, sculpture survived in folk art, woodcarving, metal work and stone carving.

Fanlights are a distinct category of stone carving and are encountered primarily in the Cycladic Islands. They are semicircular with perforations and relief designs, and are placed over windows and doors, covering the load-bearing triangular openings, and have multiple functions: practical, because they allow light into the interior; aesthetic, because they have ornamental images; and even magical, because the designs are frequently of a talismanic or apotropaic nature.

The imagery used to decorate fanlights includes religious and human figures, animals, birds and plant motifs, geometric shapes, buildings and ships. Stylistically, they are a combination of elements from the West, the East and folk tradition.

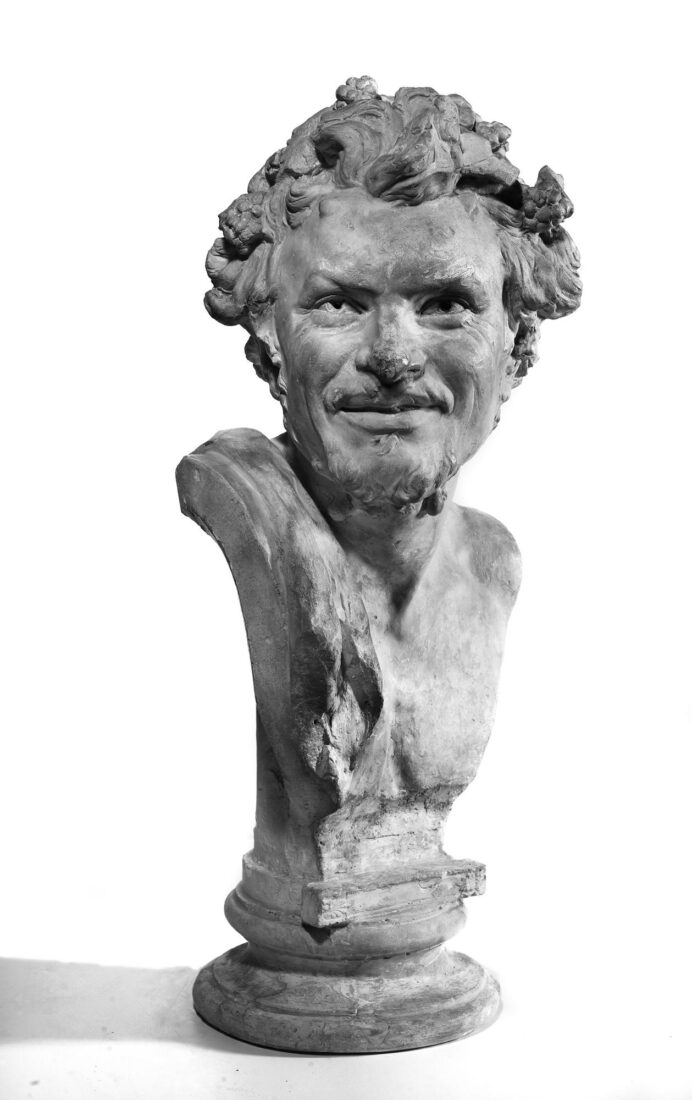

Yannoulis Chalepas was a uniquely gifted artist. But his life and artistic development were marked by the manifestation of mental illness that led to confinement in a psychiatric hospital on the island of Corfu and a forty-year hiatus in his artistic production. The first symptoms of aberrant behavior presented in 1878, the same year that he completed his first body of work, referred to by historians as the “first period.”

“Satyr’s Head” is among the last works of Yannoulis Chalepas’ first creative period. A realistic, highly modeled figure, it is a virtually psychographic, personal portrait of a mature man. The vivid, penetrating gaze and enigmatic smile establish the figure’s personality. The smile appears at once sarcastic or demonic and melancholy, depending on the angle from which it is regarded. In fact, this piece caused Chalepas such emotional distress that he tried to destroy it by scratching and throwing clay at it.

Michalis Tombros was a leader in disseminating avant-garde European currents in Greek art. He lived and worked in Paris from 1925 to 1928, yet he had visited the French capital three times already. This three-year stay in the French capital was decisive in shaping his enterprise. The influence of Rodin’s descendents is recognized in many female figures that were created during that period. The “Stout Seated Woman” is a characteristic example. A woman with ample curves does not represent the physical ideal, but adheres to the prototype of similar figures by Aristide Maillol. The views of the French artist on the modeling of the female nude were decisive for both Tombros and other Greek sculptors as well. Thus the figure, with an expression of anticipation and forbearance is conveyed in a closed, compact form with robust curves and a clean outline. Without becoming consumed in descriptive details, the artist shapes large, clear volumes with no voids, creating a solid piece that imposes itself on the space with its stillness and calm.

Michalis Tombros pioneered in the dissemination of avant-garde movements in Modern Greek art. From 1925 to 1928 he lived and worked in Paris, but had already visited the French capital three times. The last three years of his stay were a turning point in shaping his style, which is characterised by a prominent duality: on the one hand, figurative (female figures), clearly influenced by the sculpture of Aristide Maillol, and public monuments in the academic style, and, on the other hand, cubist or surrealistic compositions from the late 1920s on. He focused more consistently to surrealistic works, however, since around 1950. Thus, works such as “Elf”, revolve around, or combine, organic and vegetable motifs with geometric patterns and outlandish creatures, with references to the sculpture of Alexander Archipenko and Ossip Zadkine.

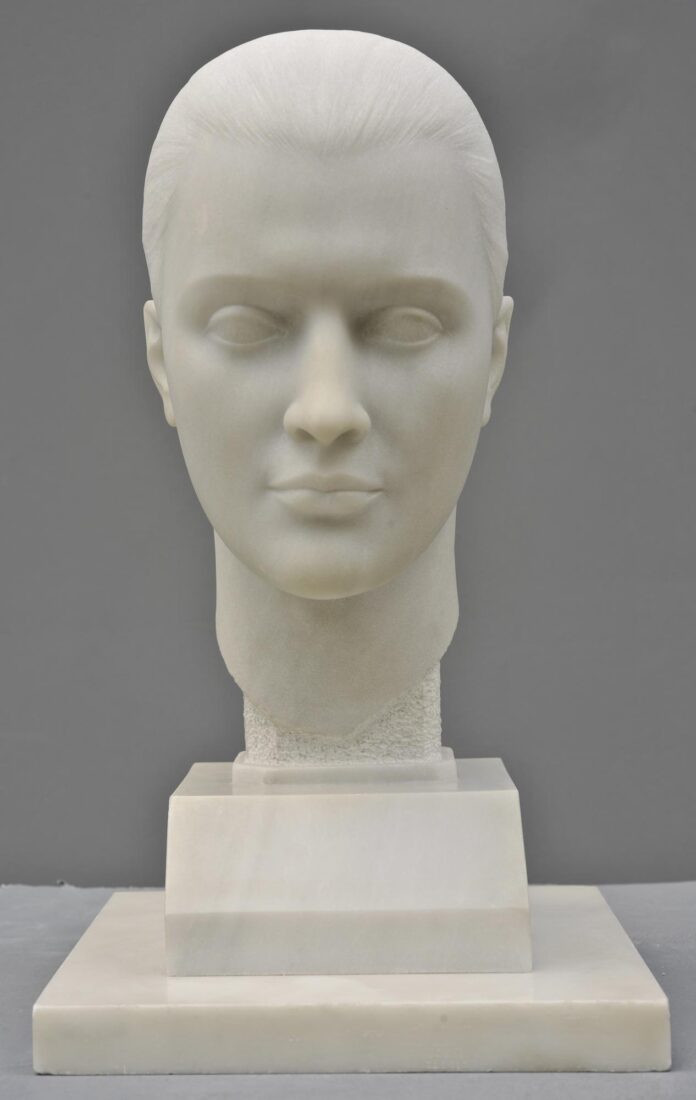

Antonios Sochos was one of the first sculptors to distance himself from neoclassicist doctrines and turn in a completely different direction. His study of archaic plastic art from the 7th and 6th century BC, of Cycladic figurines, as well as Gothic art, coupled with his initiation into the long tradition of folk sculpture on Tinos in combination with an acquaintance with the avant garde movements in Europe were the sources of his inspiration.

“Head of Kore”, carved directly into porous stone, with the beautiful features, the expressive face and the slight but thoughtful frown, makes it obvious that he drew his inspiration from the “Kores” on the Acropolis. The frontal rendering, the lips, the eyebrows and the pupils of the eye which are lightly made-up, the stylized hair-style which softly frames the face and even the material itself, connect this work to the figures of archaic plastic art, while the incorporated base, which creates a compact volume with the head and the neck, serves as a reference to ancient hermaic steles.

An autodidact by conviction, an innovator and an inventor, Takis combined through his personal idiom science and art in his works. The energy that exists in nature, light, as well as motion in all its forms are the elements which constituted the prime focus of his investigations as early as the beginning of the Fifties and which eventually led to series such as “Signals”, “Telemagnetics”, “Hydromagnetics”, “Musical” and “Photovoltaic Sculptures”.

The series “Interior Spaces” was started in 1957; it is based on nature’s energy and consists of spheres cast in bronze. Takis created these sculptures by exploiting the centrifugal force which is produced by inflating something. To achieve the desired result he filled ordinary balloons with air, and then carefully made a plaster cast before casting them in bronze. Some of these spheres bear the traces of the metal bands that were wrapped tightly around the balloons and thus record the pressure caused by their contact with the inflated surface. Moreover, some times this energy caused bumps which resemble strange heads.

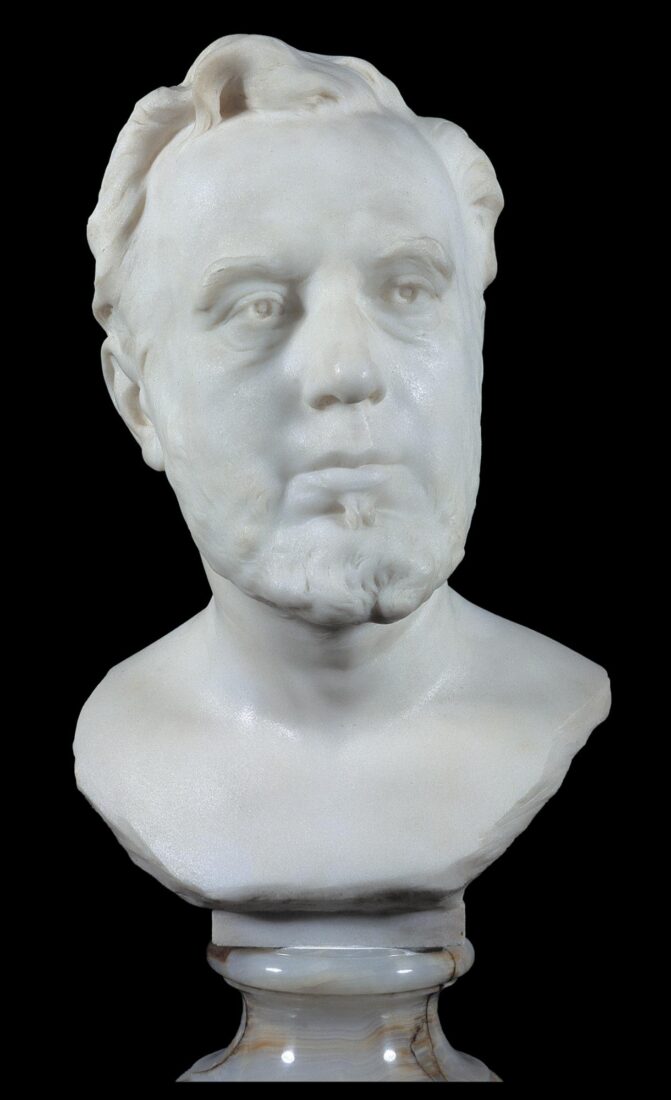

Lazaros Sochos, an artist with a neoclassicist education, was the first Greek sculptor to continue his studies in Paris rather than Munich or Italy. Living during a transitional period for modern Greek sculpture he did not completely reject neoclassicist influences, but rather combined them with realistic elements and his own personal idealistic perceptions which went hand in hand with the more general spirit of the times.

Busts, as a thematic entity, sparked his interest to a great degree. In contrast, however, to the customary sterile and lifeless style which was often encountered in such works, the busts done by Lazaros Sochos were exceptions to the rule in their endeavor to give a psychographic rendering of the person depicted. The bust of Dimitrios Vikelas, who played a leading role in the organization of the first Olympic Games in Athens in 1896 and the anastylosis of the Panathenaikon Stadium, and whom Sochos got to know during his residence in Paris, is rendered in a realistic manner, while a tendency to idealize the figure is expressed as well. The clear brow, the eyes, the cheeks, the beard, the hair and the chest are moulded with soft surfaces and fluid outlines, in keeping with Rodin’s style, who dominated the artistic forestage during the period Sochos was in Paris. The bareness of the chest, conversely, and the circular base are remnants of his neoclassicist education.

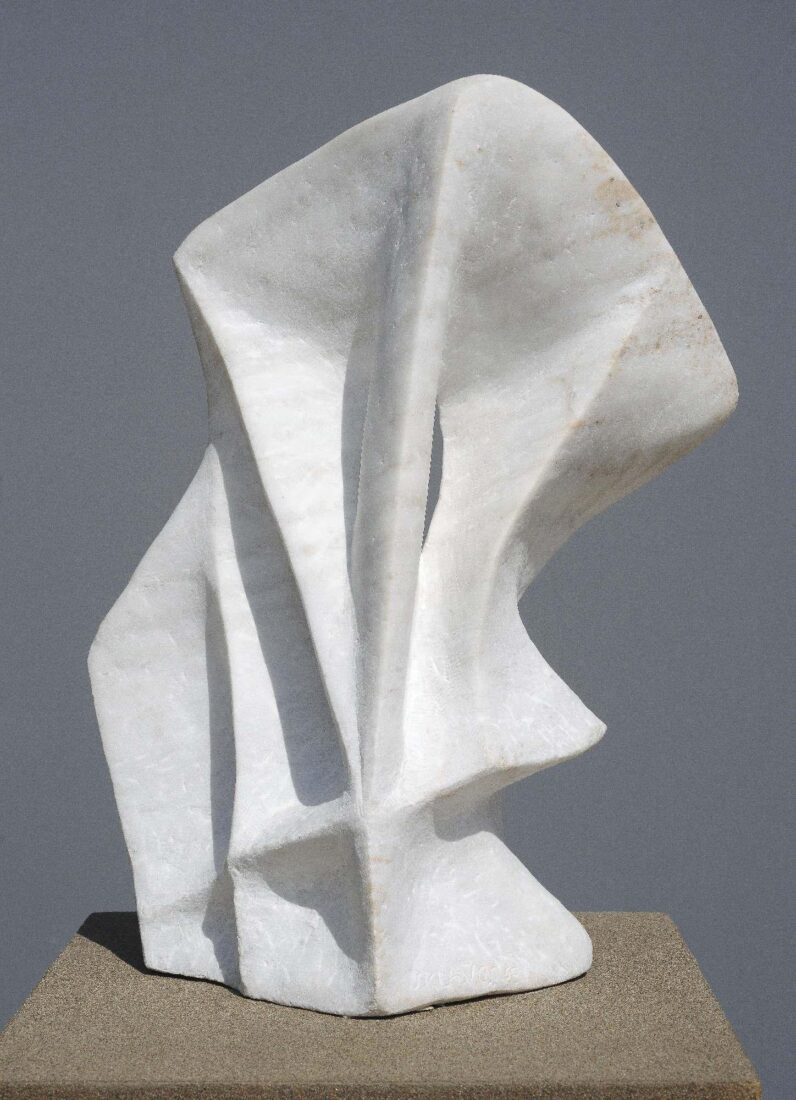

Yerassimos Sklavos, though he died barely forty years old, left behind a rich collection of completed works, based in large part on research and experiments concerned with how materials should be worked. Figurative rendering, with the human figure as the focus, occupied him for a brief period, until 1959, since his inclination to abstraction was innate and expression by means of non-figurative shapes just a matter of time. He preferred hard materials – marble, porphyrite, granite, quartzite and, more infrequently, iron and wood – and followed the traditional method of direct carving, while in 1960 he invented “telesculpture”, a personal technique by which he carved the materials more easily, using oxygen and acetylene flame. Thus, he excluded the random and exploited the possibilities of the light to the full, which he considered the beginning of the universe and the creation.

“Lightning” is fashioned from a compact volume of marble, with many angles to view it from, carved in such a way that the light traverses the surface, creating levels both illuminated and dark at opportune points. In this way it brings the material’s texture to prominence.

Gabriela Simossi worked in the framework of representational art, but in a manner which served to bring inspirations with a strong surrealistic and at the same time poetic character to fruition, based in large part on memories derived from ancient Greek sculpture. The mutilated statues for the most part became the motivation to produce her own fragmentary compositions, which have an enigmatic style and are emotionally charged, most likely as the result of her own personal experiences. The whiteness of plaster, furthermore, of a material she makes frequent use of, contributes to an impression of silence and confinement in her work, qualities that can be recognized in a considerable number of her works.

In “The Eraser” the dominant element is the feeling of non-existence. A female face, melancholic but at the same time resolved, a type repeated in rather a large number of her works, is projected in relief within an indeterminate environment and is seen disappearing slowly under the movement of an eraser which leaves its traces on the surface in a symbolic gesture of deleting the being.

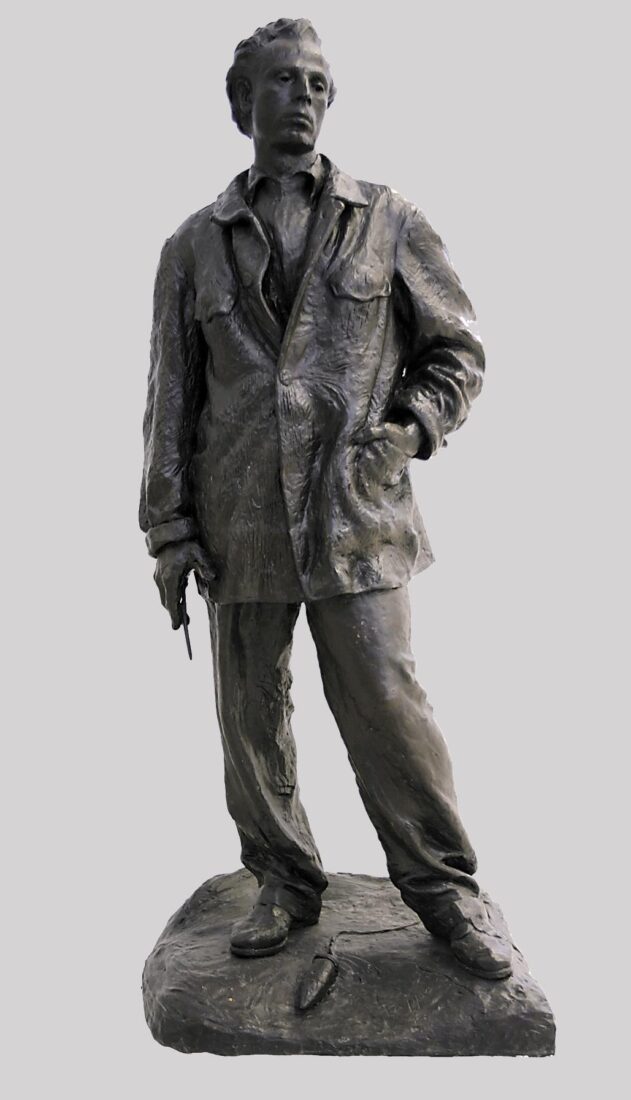

Yannis Pappas remained faithful to the figurative depiction focused on the human being throughout his entire artistic career. Guided by nature and tradition he moulded, drew and painted the human figure, initially placing his stress on a realistic and detailed rendering and eventually seeking to express the essence of the subject, using a simplified and more abstract manner, which echoes both archaic Greek and Egyptian sculpture, as well as the contemporary trends.

During his stay in Paris he made the sculptures of Christos Kapralos (1936) and Yannis Moralis (1937), two very characteristic early works. The differences in the rendering of these works indicate the style that he will adopt in his later compositions.

Making use of a completely realistic approach, Pappas moulded Christos Kapralos in an open and relaxed composition, in which the spontaneous and well-balanced pose, the placement of the hands, and the clothes, the head slightly turned, and the expression on the face, are all combined together in order to render this unsophisticated young artist who was in the French capital and, despite his hesitations and fears, had the hope of succeeding and the temperament to accomplish it.

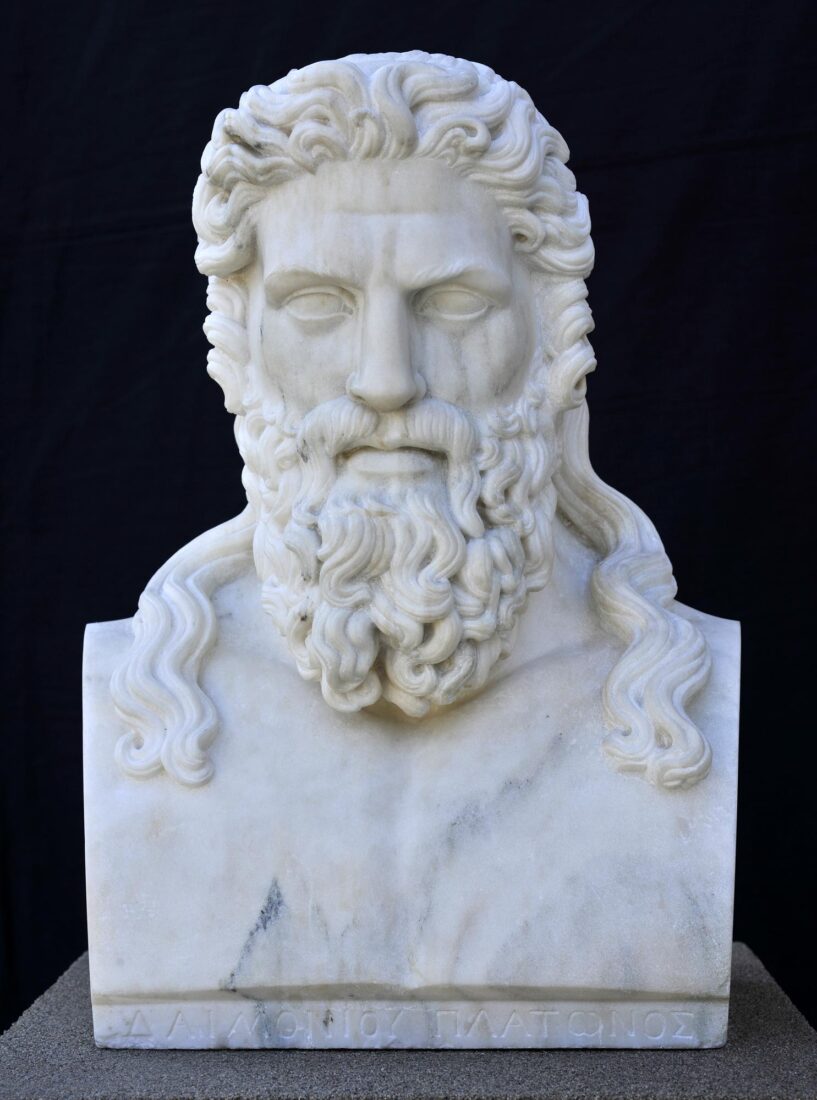

Sculpture appeared as an autonomous art form in Greece in the Ionian Islands at the beginning of the 19th century. Corfu native Pavlos Prosalent, the Elder the first Greek sculptor with academic training. He studied at St. Luke’s Academy in Rome and was responsible for bringing neoclassical teachings to the Ionian Islands.

His bust of Plato is one of the first works of his mature period. In fact, the sculptor has engraved an inscription on its side that proudly declares it to be the first bust in modern Greek art. The figure of the ancient philosopher is rendered with a serious, pensive gaze, a broad, clear forehead, strongly chiseled characteristics, a full, well-groomed beard, and long hair. Prosalentis has carved an idealized figure more divine than human, in keeping with neoclassical ideals. This divine aspect is accentuated by the ribbon tied around the head and by the inscription “Daimonios”, meaning divine.