Giorgos Chouliaras fashioned his own personal style through his studying under Yannis Pappas at the Athens School of Fine Arts, his close examination of ancient Greek art and the folk tradition, and the contact with contemporary trends. These elements have determined the use his materials are put to – porous stone, plain stone, granite and cement initially, and then later marble, bronze, aluminum, steel and iron.

The human figure was his main preoccupation in his earliest compositions, but rendered very schematically, containing elements borrowed from folk sculpture. His inclination toward abstraction had made itself obvious by the beginning of the Eighties, with works such as “Memory”, carved in granite, stone or marble. These compositions are the result of the plastic fashioning of a compact volume with ridges and depressions based on geometric or organic shapes, which allow the light to traverse the surface, thus projecting both the shapes and the texture of the material.

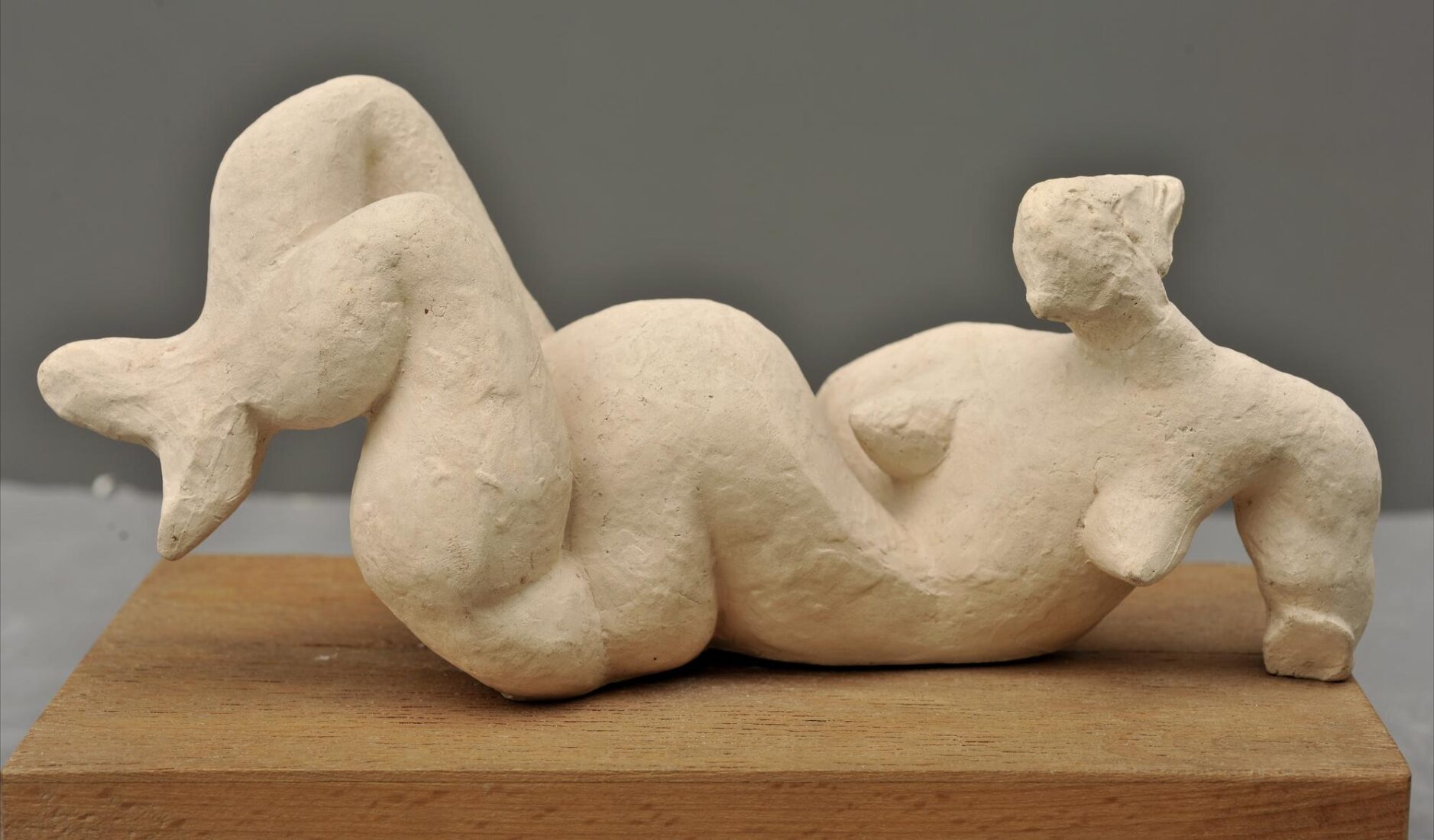

In 1918, 40 long years after the first manifestation of the symptoms of a deviating behaviour which led to the artist’s institutionalisation for 14 years, Yannoulis Chalepas’s second period as an artist began. During that time, Chalepas exhibited a totally different style: free and spontaneous, independent of academic training, guided by ancient Greek art. He now focused on the essence of each work, as he was not interested in detailed processing, refinement, or idealisation. His figures now became introverted (“St Barbara and Hermes“), solid and imposing (“Medea III“), almost hieratic at times (“Hermes, Pegasus and Aphrodite“). He gives, using spare means, the tone in the pose or facial expression and transforms his works into psychographic portraits (“St Barbara and Hermes“,“Resting female figure“,“Hermes, Pegasus and Aphrodite“). Moreover, several complementary elements, probably of an obscure symbolic meaning (“Medea III“), often add to the main theme and give a surreal tone to the work as a whole. The artist made clay models, not seeking a more finished version; he was engaged in several works at the same time. Not using an internal frame, he continued to make works inspired by the Greek antiquity and mythology (“St Barbara and Hermes“, “Hermes, Pegasus and Aphrodite“, “Medea III“), figures inspired by the urban environment, or his village (“Harvester“, “Hunter“), female nudes (“Reclining female figure“, “Small reclining female figure“), different-scale figures combined, as well as his characteristic as much as hard to interpret works (“The secret“,“ The thought“, “St Barbara and Hermes“), selecting themes suggestive of his personal experiences.

In 1918, 40 long years after the first manifestation of the symptoms of a deviating behaviour which led to the artist’s institutionalisation for 14 years, Yannoulis Chalepas’s second period as an artist began. During that time, Chalepas exhibited a totally different style: free and spontaneous, independent of academic training, guided by ancient Greek art. He now focused on the essence of each work, as he was not interested in detailed processing, refinement, or idealisation. His figures now became introverted (“St Barbara and Hermes“), solid and imposing (“Medea III“), almost hieratic at times (“Hermes, Pegasus and Aphrodite“). He gives, using spare means, the tone in the pose or facial expression and transforms his works into psychographic portraits (“St Barbara and Hermes“,“Resting female figure“,“Hermes, Pegasus and Aphrodite“). Moreover, several complementary elements, probably of an obscure symbolic meaning (“Medea III“), often add to the main theme and give a surreal tone to the work as a whole. The artist made clay models, not seeking a more finished version; he was engaged in several works at the same time. Not using an internal frame, he continued to make works inspired by the Greek antiquity and mythology (“St Barbara and Hermes“, “Hermes, Pegasus and Aphrodite“, “Medea III“), figures inspired by the urban environment, or his village (“Harvester“, “Hunter“), female nudes (“Reclining female figure“, “Small reclining female figure“), different-scale figures combined, as well as his characteristic as much as hard to interpret works (“The secret“,“ The thought“, “St Barbara and Hermes“), selecting themes suggestive of his personal experiences.

In 1918, 40 long years after the first manifestation of the symptoms of a deviating behaviour which led to the artist’s institutionalisation for 14 years, Yannoulis Chalepas’s second period as an artist began. During that time, Chalepas exhibited a totally different style: free and spontaneous, independent of academic training, guided by ancient Greek art. He now focused on the essence of each work, as he was not interested in detailed processing, refinement, or idealisation. His figures now became introverted (“St Barbara and Hermes“), solid and imposing (“Medea III“), almost hieratic at times (“Hermes, Pegasus and Aphrodite“). He gives, using spare means, the tone in the pose or facial expression and transforms his works into psychographic portraits (“St Barbara and Hermes“,“Resting female figure“,“Hermes, Pegasus and Aphrodite“). Moreover, several complementary elements, probably of an obscure symbolic meaning (“Medea III“), often add to the main theme and give a surreal tone to the work as a whole. The artist made clay models, not seeking a more finished version; he was engaged in several works at the same time. Not using an internal frame, he continued to make works inspired by the Greek antiquity and mythology (“St Barbara and Hermes“, “Hermes, Pegasus and Aphrodite“, “Medea III“), figures inspired by the urban environment, or his village (“Harvester“, “Hunter“), female nudes (“Reclining female figure“, “Small reclining female figure“), different-scale figures combined, as well as his characteristic as much as hard to interpret works (“The secret“,“ The thought“, “St Barbara and Hermes“), selecting themes suggestive of his personal experiences.

In 1918, 40 long years after the first manifestation of the symptoms of a deviating behaviour which led to the artist’s institutionalisation for 14 years, Yannoulis Chalepas’s second period as an artist began. During that time, Chalepas exhibited a totally different style: free and spontaneous, independent of academic training, guided by ancient Greek art. He now focused on the essence of each work, as he was not interested in detailed processing, refinement, or idealisation. His figures now became introverted (“St Barbara and Hermes“), solid and imposing (“Medea III“), almost hieratic at times (“Hermes, Pegasus and Aphrodite“). He gives, using spare means, the tone in the pose or facial expression and transforms his works into psychographic portraits (“St Barbara and Hermes“,“Resting female figure“,“Hermes, Pegasus and Aphrodite“). Moreover, several complementary elements, probably of an obscure symbolic meaning (“Medea III“), often add to the main theme and give a surreal tone to the work as a whole. The artist made clay models, not seeking a more finished version; he was engaged in several works at the same time. Not using an internal frame, he continued to make works inspired by the Greek antiquity and mythology (“St Barbara and Hermes“, “Hermes, Pegasus and Aphrodite“, “Medea III“), figures inspired by the urban environment, or his village (“Harvester“, “Hunter“), female nudes (“Reclining female figure“, “Small reclining female figure“), different-scale figures combined, as well as his characteristic as much as hard to interpret works (“The secret“,“ The thought“, “St Barbara and Hermes“), selecting themes suggestive of his personal experiences.

The subject of this piece is taken from the parable of the Prodigal Son as narrated in the Gospel according to Luke. The younger of two sons asked his father to divvy up his fortune and give him his share. The son then took the money, left home and squandered it in a foreign town, where he succumbed to hunger. Unable to sustain himself, he recalled that the slaves in his father’s household were living better that he was. So, repentant, he returned home, entreating his father to take him in as a slave, saying, “Father I have sinned against heaven and before you, and I no longer deserve to call myself your son.” His father, however, welcomed him with open arms and restored him to his rightful place in the home.

The moment of the Son-Man’s apology to the Father-God is depicted in a stance of intense supplication, with the figure’s torso straining backward and hands upraised towards heaven.

This piece synopsizes Rodin’s artistic ideals. Opposed to the imitation of reality pursued by the conservative academic artists of his day, he created powerfully expressive, deeply symbolic sculptural forms through the use of poses with excessive physical tension. The body here is muscular and sinewy, modeled with deep groves and incidents that heighten the sensation of agony, passion and desperation. Regarding this piece, Rodin confessed to Paul Gsell (Auguste Rodin on Art and Artists, p. 11) that he emphasized the muscle mass to express misery and in some places exaggerated the stretched tendons to make the outburst of remorse and entreaty more obvious.

Although this scene involves at least two persons, the son and the father, the presence of the latter is intangible, implied only by the movement of the son’s body and upraised hands.

This piece was shown for the first time in 1894 as The Boy of the Century at the Salon organized by the newspaper La Plume. However, it was exhibited with its current title at a pavilion of Rodin’s works at the 1900 Exposition Universelle in Paris.

The source of this figure is La Porte de l’Enfer (The Gates of Hell), from which Rodin isolated and developed a number of subsequent images. He frequently used variations of the same figure in different images, giving them different significance. The Prodigal Son comes from Fugit Amor, a group on the right section of the Gates. This monumental work was commissioned for the entrance of the future Musee des Arts Decoratif in Paris, but was never completed. Rodin nevertheless continued to work on it until his death, and its imagery resulted in a number of free-standing sculptures.

The zenith that Greek sculpture achieved in antiquity lost ground with the coming of Christianity. Christianity rejected every feature that came from the idolatrous world, thus relegating sculpture to a secondary, decorative role. In post-Byzantine times and until the early 19th century, sculpture survived in folk art, woodcarving, metal work and stone carving.

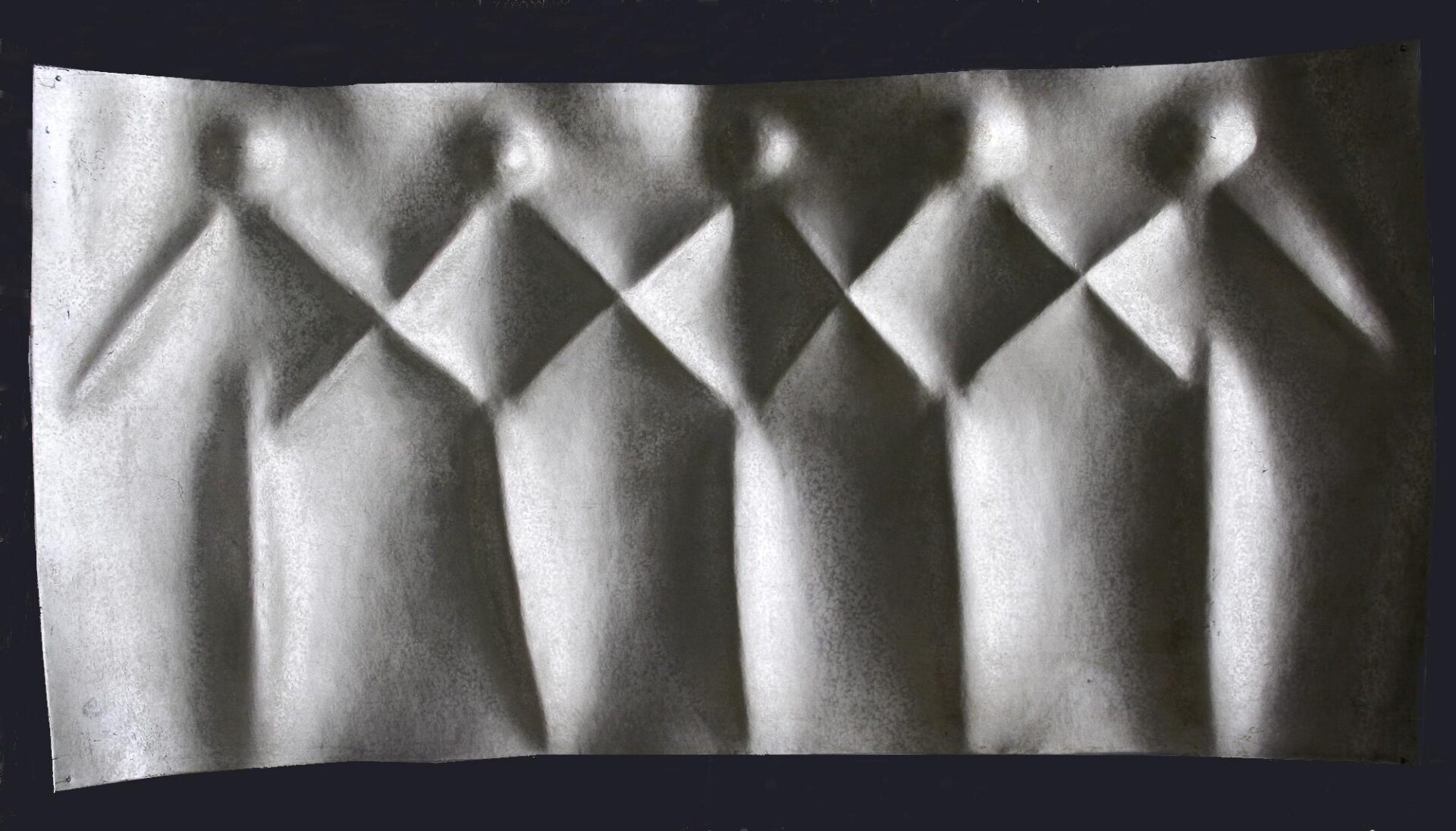

Fanlights are a distinct category of stone carving and are encountered primarily in the Cycladic Islands. They are semicircular with perforations and relief designs, and are placed over windows and doors, covering the load-bearing triangular openings, and have multiple functions: practical, because they allow light into the interior; aesthetic, because they have ornamental images; and even magical, because the designs are frequently of a talismanic or apotropaic nature.

The imagery used to decorate fanlights includes religious and human figures, animals, birds and plant motifs, geometric shapes, buildings and ships. Stylistically, they are a combination of elements from the West, the East and folk tradition.

The zenith that Greek sculpture achieved in antiquity lost ground with the coming of Christianity. Christianity rejected every feature that came from the idolatrous world, thus relegating sculpture to a secondary, decorative role. In post-Byzantine times and until the early 19th century, sculpture survived in folk art, woodcarving, metal work and stone carving.

Fanlights are a distinct category of stone carving and are encountered primarily in the Cycladic Islands. They are semicircular with perforations and relief designs, and are placed over windows and doors, covering the load-bearing triangular openings, and have multiple functions: practical, because they allow light into the interior; aesthetic, because they have ornamental images; and even magical, because the designs are frequently of a talismanic or apotropaic nature.

The imagery used to decorate fanlights includes religious and human figures, animals, birds and plant motifs, geometric shapes, buildings and ships. Stylistically, they are a combination of elements from the West, the East and folk tradition.

The zenith that Greek sculpture achieved in antiquity lost ground with the coming of Christianity. Christianity rejected every feature that came from the idolatrous world, thus relegating sculpture to a secondary, decorative role. In post-Byzantine times and until the early 19th century, sculpture survived in folk art, woodcarving, metal work and stone carving.

Fanlights are a distinct category of stone carving and are encountered primarily in the Cycladic Islands. They are semicircular with perforations and relief designs, and are placed over windows and doors, covering the load-bearing triangular openings, and have multiple functions: practical, because they allow light into the interior; aesthetic, because they have ornamental images; and even magical, because the designs are frequently of a talismanic or apotropaic nature.

The imagery used to decorate fanlights includes religious and human figures, animals, birds and plant motifs, geometric shapes, buildings and ships. Stylistically, they are a combination of elements from the West, the East and folk tradition.

The zenith that Greek sculpture achieved in antiquity lost ground with the coming of Christianity. Christianity rejected every feature that came from the idolatrous world, thus relegating sculpture to a secondary, decorative role. In post-Byzantine times and until the early 19th century, sculpture survived in folk art, woodcarving, metal work and stone carving.

Fanlights are a distinct category of stone carving and are encountered primarily in the Cycladic Islands. They are semicircular with perforations and relief designs, and are placed over windows and doors, covering the load-bearing triangular openings, and have multiple functions: practical, because they allow light into the interior; aesthetic, because they have ornamental images; and even magical, because the designs are frequently of a talismanic or apotropaic nature.

The imagery used to decorate fanlights includes religious and human figures, animals, birds and plant motifs, geometric shapes, buildings and ships. Stylistically, they are a combination of elements from the West, the East and folk tradition.

The zenith that Greek sculpture achieved in antiquity lost ground with the coming of Christianity. Christianity rejected every feature that came from the idolatrous world, thus relegating sculpture to a secondary, decorative role. In post-Byzantine times and until the early 19th century, sculpture survived in folk art, woodcarving, metal work and stone carving.

Fanlights are a distinct category of stone carving and are encountered primarily in the Cycladic Islands. They are semicircular with perforations and relief designs, and are placed over windows and doors, covering the load-bearing triangular openings, and have multiple functions: practical, because they allow light into the interior; aesthetic, because they have ornamental images; and even magical, because the designs are frequently of a talismanic or apotropaic nature.

The imagery used to decorate fanlights includes religious and human figures, animals, birds and plant motifs, geometric shapes, buildings and ships. Stylistically, they are a combination of elements from the West, the East and folk tradition.

The zenith that Greek sculpture achieved in antiquity lost ground with the coming of Christianity. Christianity rejected every feature that came from the idolatrous world, thus relegating sculpture to a secondary, decorative role. In post-Byzantine times and until the early 19th century, sculpture survived in folk art, woodcarving, metal work and stone carving.

Fanlights are a distinct category of stone carving and are encountered primarily in the Cycladic Islands. They are semicircular with perforations and relief designs, and are placed over windows and doors, covering the load-bearing triangular openings, and have multiple functions: practical, because they allow light into the interior; aesthetic, because they have ornamental images; and even magical, because the designs are frequently of a talismanic or apotropaic nature.

The imagery used to decorate fanlights includes religious and human figures, animals, birds and plant motifs, geometric shapes, buildings and ships. Stylistically, they are a combination of elements from the West, the East and folk tradition.

The zenith that Greek sculpture achieved in antiquity lost ground with the coming of Christianity. Christianity rejected every feature that came from the idolatrous world, thus relegating sculpture to a secondary, decorative role. In post-Byzantine times and until the early 19th century, sculpture survived in folk art, woodcarving, metal work and stone carving.

Fanlights are a distinct category of stone carving and are encountered primarily in the Cycladic Islands. They are semicircular with perforations and relief designs, and are placed over windows and doors, covering the load-bearing triangular openings, and have multiple functions: practical, because they allow light into the interior; aesthetic, because they have ornamental images; and even magical, because the designs are frequently of a talismanic or apotropaic nature.

The imagery used to decorate fanlights includes religious and human figures, animals, birds, plant motifs, geometric shapes, buildings and ships. Stylistically, they are a combination of elements from the West, the East and folk tradition.