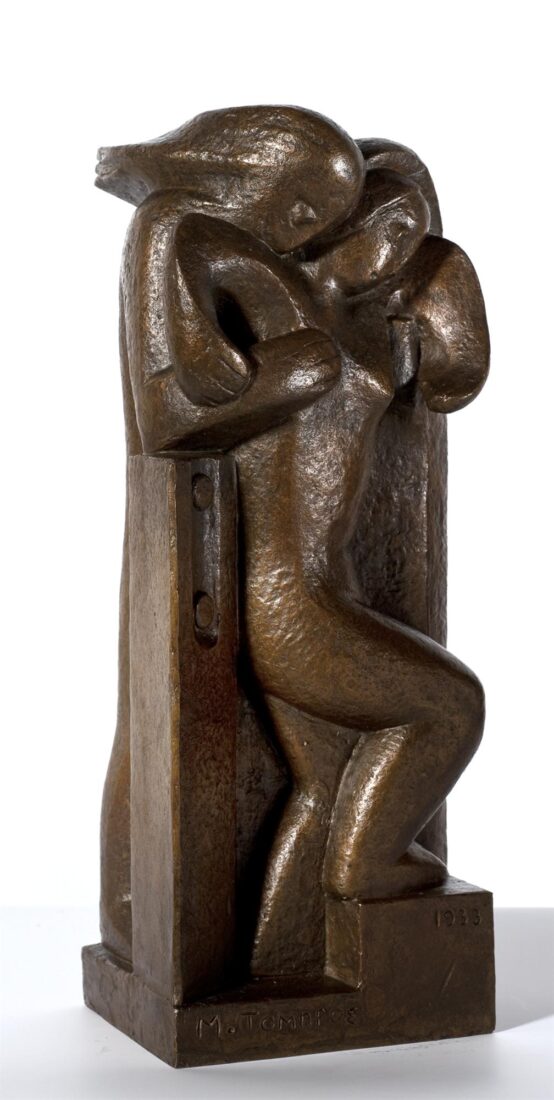

In 1918, 40 long years after the first manifestation of the symptoms of a deviating behaviour which led to the artist’s institutionalisation for 14 years, Yannoulis Chalepas’s second period as an artist began. During that time, Chalepas exhibited a totally different style: free and spontaneous, independent of academic training, guided by ancient Greek art. He now focused on the essence of each work, as he was not interested in detailed processing, refinement, or idealisation. His figures now became introverted (“St Barbara and Hermes“), solid and imposing (“Medea III“), almost hieratic at times (“Hermes, Pegasus and Aphrodite“). He gives, using spare means, the tone in the pose or facial expression and transforms his works into psychographic portraits (“St Barbara and Hermes“,“Resting female figure“,“Hermes, Pegasus and Aphrodite“). Moreover, several complementary elements, probably of an obscure symbolic meaning (“Medea III“), often add to the main theme and give a surreal tone to the work as a whole. The artist made clay models, not seeking a more finished version; he was engaged in several works at the same time. Not using an internal frame, he continued to make works inspired by the Greek antiquity and mythology (“St Barbara and Hermes“, “Hermes, Pegasus and Aphrodite“, “Medea III“), figures inspired by the urban environment, or his village (“Harvester“, “Hunter“), female nudes (“Reclining female figure“, “Small reclining female figure“), different-scale figures combined, as well as his characteristic as much as hard to interpret works (“The secret“,“ The thought“, “St Barbara and Hermes“), selecting themes suggestive of his personal experiences.

In 1918, 40 long years after the first manifestation of the symptoms of a deviating behaviour which led to the artist’s institutionalisation for 14 years, Yannoulis Chalepas’s second period as an artist began. During that time, Chalepas exhibited a totally different style: free and spontaneous, independent of academic training, guided by ancient Greek art. He now focused on the essence of each work, as he was not interested in detailed processing, refinement, or idealisation. His figures now became introverted (“St Barbara and Hermes“), solid and imposing (“Medea III“), almost hieratic at times (“Hermes, Pegasus and Aphrodite“). He gives, using spare means, the tone in the pose or facial expression and transforms his works into psychographic portraits (“St Barbara and Hermes“,“Resting female figure“,“Hermes, Pegasus and Aphrodite“). Moreover, several complementary elements, probably of an obscure symbolic meaning (“Medea III“), often add to the main theme and give a surreal tone to the work as a whole. The artist made clay models, not seeking a more finished version; he was engaged in several works at the same time. Not using an internal frame, he continued to make works inspired by the Greek antiquity and mythology (“St Barbara and Hermes“, “Hermes, Pegasus and Aphrodite“, “Medea III“), figures inspired by the urban environment, or his village (“Harvester“, “Hunter“), female nudes (“Reclining female figure“, “Small reclining female figure“), different-scale figures combined, as well as his characteristic as much as hard to interpret works (“The secret“,“ The thought“, “St Barbara and Hermes“), selecting themes suggestive of his personal experiences.

In 1918, 40 long years after the first manifestation of the symptoms of a deviating behaviour which led to the artist’s institutionalisation for 14 years, Yannoulis Chalepas’s second period as an artist began. During that time, Chalepas exhibited a totally different style: free and spontaneous, independent of academic training, guided by ancient Greek art. He now focused on the essence of each work, as he was not interested in detailed processing, refinement, or idealisation. His figures now became introverted (“St Barbara and Hermes“), solid and imposing (“Medea III“), almost hieratic at times (“Hermes, Pegasus and Aphrodite“). He gives, using spare means, the tone in the pose or facial expression and transforms his works into psychographic portraits (“St Barbara and Hermes“,“Resting female figure“,“Hermes, Pegasus and Aphrodite“). Moreover, several complementary elements, probably of an obscure symbolic meaning (“Medea III“), often add to the main theme and give a surreal tone to the work as a whole. The artist made clay models, not seeking a more finished version; he was engaged in several works at the same time. Not using an internal frame, he continued to make works inspired by the Greek antiquity and mythology (“St Barbara and Hermes“, “Hermes, Pegasus and Aphrodite“, “Medea III“), figures inspired by the urban environment, or his village (“Harvester“, “Hunter“), female nudes (“Reclining female figure“, “Small reclining female figure“), different-scale figures combined, as well as his characteristic as much as hard to interpret works (“The secret“,“ The thought“, “St Barbara and Hermes“), selecting themes suggestive of his personal experiences.

In 1918, 40 long years after the first manifestation of the symptoms of a deviating behaviour which led to the artist’s institutionalisation for 14 years, Yannoulis Chalepas’s second period as an artist began. During that time, Chalepas exhibited a totally different style: free and spontaneous, independent of academic training, guided by ancient Greek art. He now focused on the essence of each work, as he was not interested in detailed processing, refinement, or idealisation. His figures now became introverted (“St Barbara and Hermes“), solid and imposing (“Medea III“), almost hieratic at times (“Hermes, Pegasus and Aphrodite“). He gives, using spare means, the tone in the pose or facial expression and transforms his works into psychographic portraits (“St Barbara and Hermes“,“Resting female figure“,“Hermes, Pegasus and Aphrodite“). Moreover, several complementary elements, probably of an obscure symbolic meaning (“Medea III“), often add to the main theme and give a surreal tone to the work as a whole. The artist made clay models, not seeking a more finished version; he was engaged in several works at the same time. Not using an internal frame, he continued to make works inspired by the Greek antiquity and mythology (“St Barbara and Hermes“, “Hermes, Pegasus and Aphrodite“, “Medea III“), figures inspired by the urban environment, or his village (“Harvester“, “Hunter“), female nudes (“Reclining female figure“, “Small reclining female figure“), different-scale figures combined, as well as his characteristic as much as hard to interpret works (“The secret“,“ The thought“, “St Barbara and Hermes“), selecting themes suggestive of his personal experiences.

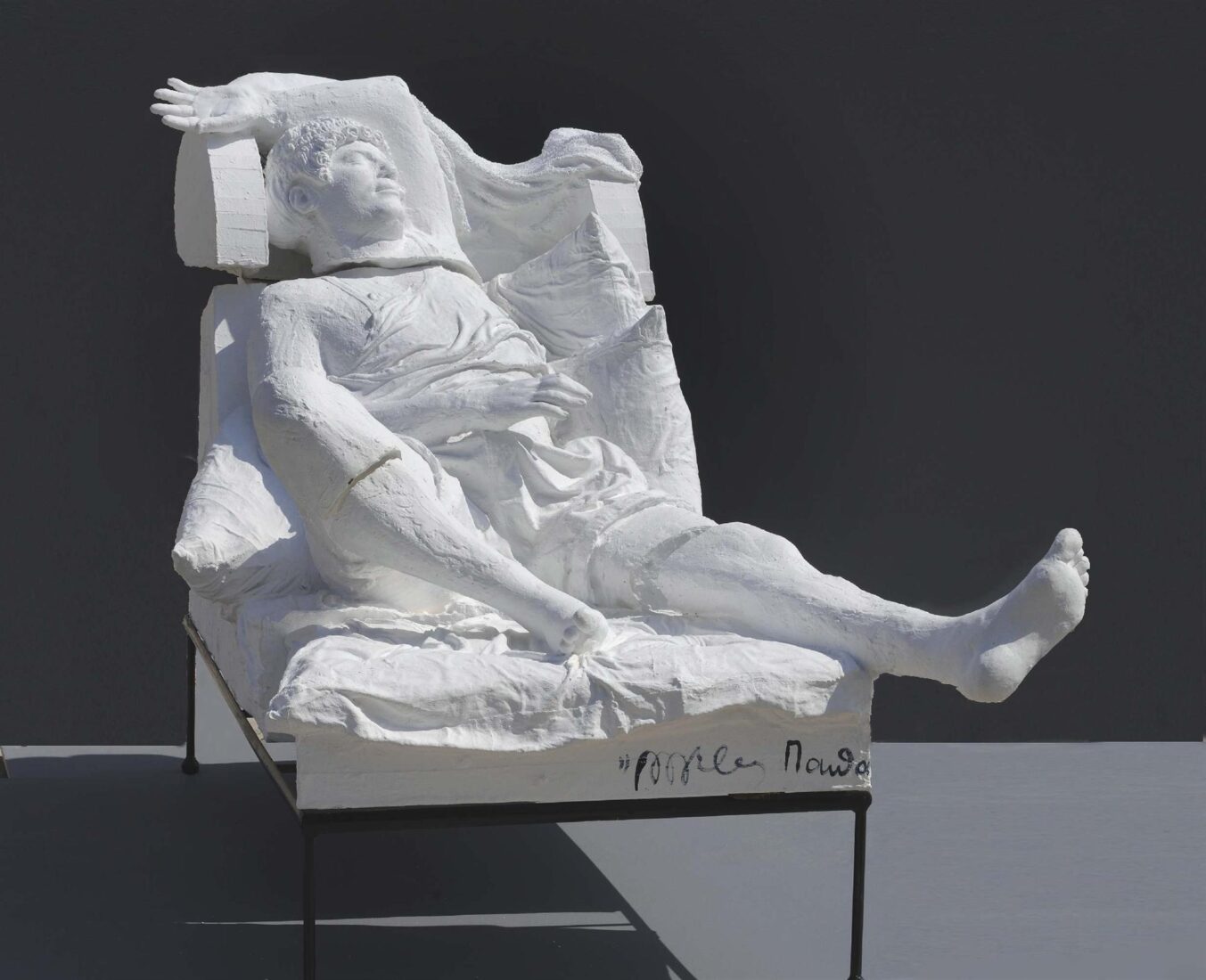

Yannis Pappas remained faithful to the figurative depiction focused on the human being throughout his entire artistic career. Guided by nature and tradition he moulded, drew and painted the human figure, initially placing his stress on a realistic and detailed rendering and eventually seeking to express the essence of the subject, using a simplified and more abstract manner. His style echoes both archaic Greek and Egyptian sculpture, as well as the contemporary trends.

During his stay in Paris he made the sculptures of Christos Kapralos (1936) and Yannis Moralis (1937), two very characteristic early works. The differences in the rendering of these works indicate the style that he will adopt in his later compositions. While Kapralos is characterized by intense realism, Yannis Moralis’s sculpture is characterized by the essential and the details are stressed in a discreet and selective manner in specific parts of the face and the body. Thus they forewarn the more abstract style which will characterize his later works.

Since the 1980s, certain artists began to use unprocessed natural materials, sometimes combining them with traditional and modern materials and sometimes with industrial ones, depending on the content and effect sought in their works.

In 1987, Pantelis Chandris began to depict natural elements in sculptures, mountains on the wall and an assortment of trees. In the early 1990s, he introduced natural materials in his work, such as grass, wood and soil. Combining these materials with ready-made industrial materials, such as plaster and iron, he produced “Trophies”, a series of sculptural incarnations of trees, which combine to form a nest. Shelters, or places where new life begins, these nests are sculptural evocations of the natural landscape, reminding us of the primary needs and yearnings of humans.

Pantelis Chandris studied graphic arts and painting, but his enterprise has a clear conceptual direction that is expressed primarily through constructions and manipulations of the space. These constructions and spatial manipulations draw either on nature or on human needs and pursuits connected to the conscious and unconscious. They are fashioned with the help of a visual reality that nonetheless has a symbolic character.

The male figure in an overcoat appeared for the first time in the trilogy “Conversations with a Wintry Figure”. It then became the basic figure in a series of pieces bearing the general title “States of Being”. “Hunter” comes from this series.

According to Chandris, the hunter-predator is identified with the Ego, the dog, the essential hunter, with the Superego, and the bird with the Id. Thus he gives form to a psychoanalytical structure as Freud analyzed it. The symbolic combination of these three figures enables Chandris to express a variety of conscious and unconscious states of being while allowing the viewer to interpret the work from a personal perspective.

Frosso Michalea chose to express herself through abstraction since, even during her brief stint doing figurative depictions of the human figure, she used strong schematization. She made use of different materials, such as marble, wood, and stone in order to realize series of works such as “Dialogues”, “Landmarks” and “Transformations”. During the Eighties she turned to metal, giving form in 1985 to the series “Movement in Space and Time”, using steel as her material and at the same time introducing color into her works. Furthermore, while her forms until then had been closed and the compositions static, with this series she introduced the feeling of latent motion that was constantly developing. The steel sheets she made use of were constructed on the basis of careful calculations, measurements and plans and assembled with bolts thus giving form to compositions which unwind rhythmically in various directions, with either a horizontal or vertical development, and created the impression of eternal movement.

Until practically the end of the Fifties, Natalia Mela made works primarily on commission, as well as a series of busts that faithfully reproduced her lessons at the Athens School of Fine Arts. In 1960 she abandoned the use of marble and stone and turned to metal, adopting at the same time a style freer and more abstract. Animals and birds, as well as mythological figures in dynamic poses, rendered schematically, but done with a roughly-worked surface with the later addition of pieces of metal to form linear constructions in space, were thus transformed into symbols of a natural demonic power. In her most recent work her interest has remained focused on figures from the animal kingdom, but her materials have been enriched. “Owl” is a characteristic example of her work these past few years and her turn to compact figures with the use of new materials. Static, with an intense look to them, eyes stressed and formed of two inset marbles and using angular contours, she brings to realization, exercising a contemporary eye, the ancient symbol of wisdom.

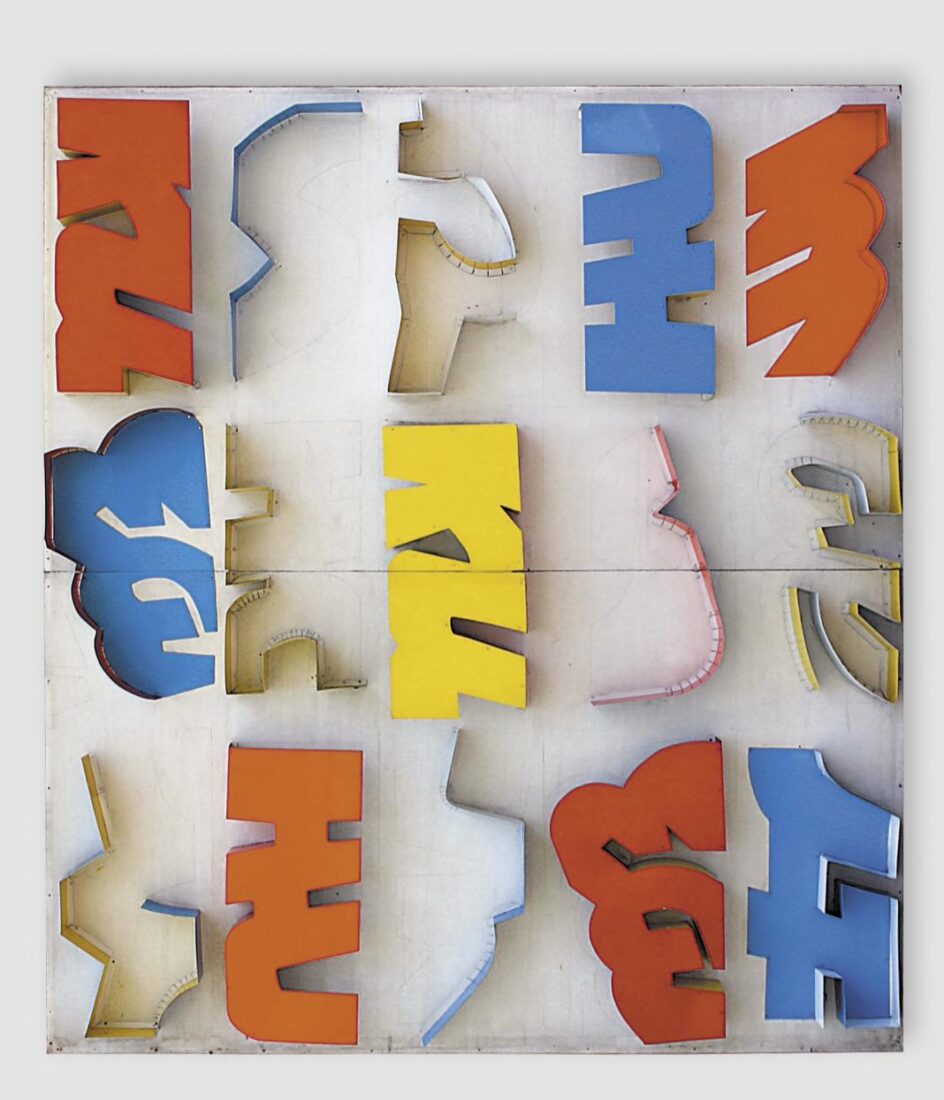

A Greek of the diaspora, Chryssa settled permanently in New York in 1955. There she soon came into contact with avant garde currents. This fact unquestionably contributed to the focus of her interest right from the beginning of her career on non-traditional ways of expression, ones not connected to figurative depiction. Thus her first works in the mid-Fifties, called “Studies of Static Light”, consisted of large plaster or metal reliefs based on asymmetrically placed arrows and letters which were transformed by the play of light. The series “Cycladic Books” were derived from the prints made by cardboard boxes on randomly poured plaster. Subsequently she began to make repeated use of various communication motifs on a variety of combinations making repeated use of the elements, and the antitheses of light and shadow, thereby creating a plastic language of signs. The result is similar works which arise from an original idea and finally come to form entities, using materials that are used in contemporary technology, such as neon tubes, aluminum and plastic.

“Gates of Times Square” is a colossal allegorical composition which arose from the assemblage of various elements and materials used in communication. This work was the motivating force for an entity of works based on elements of the initial composition, such as the relief construction with the ideogrammatic rendering of the motifs in plastic exhibited at the National Glyptotheque, which renders with a different look the polychromy and phantasmagoria of Times Square.

Frosso Michalea chose to express herself through abstraction since, even during her brief stint doing figurative depictions of the human figure, she used strong schematization. She made use of different materials, such as marble, wood, and stone in order to realize series of works such as “Dialogues”, “Landmarks” and “Transformations”. During the Eighties she turned to metal, giving form in 1985 to the series “Movement in Space and Time”, using steel as her material and at the same time introducing color into her works. Furthermore, while her forms until then had been closed and the compositions static, with this series she introduced the feeling of latent motion that was constantly developing. The steel sheets she made use of were constructed on the basis of careful calculations, measurements and plans and assembled with bolts thus giving form to compositions which unwind rhythmically in various directions, with either a horizontal or vertical development, and created the impression of eternal movement.

George Zongolopoulos started out by reproducing the human figure, but turned to abstraction in the early 60s. His earliest works were solid, tectonic sculptures. These were followed by optical-kinetic constructions assembled from nickel, glass and Plexiglas. Then, stainless metal, lenses, springs, umbrellas, rods, and nails became the fundamental elements of his creations. Water and sound and the exploitation of light contributed to the final impression.

A significant portion of Zongolopoulos’ oeuvre is made up of his constructivist compositions that incorporate the void, elevating it to an important factor in the presentation of the piece. “Composition of Circles” is one of his pieces that is based on the combination and repetition of a geometric shape – in this case the circle. Zongolopoulos used six equal-sized circles that penetrate one-another perpendicularly and diagonally. The planes of empty space that their perimeters produce intersect one-another, while simultaneously creating the impression of perpetual circular motion. Five circles are suspended nearly on top of two straight bands that form a right angle. The sixth, placed perpendicularly, balances the support of the construction.

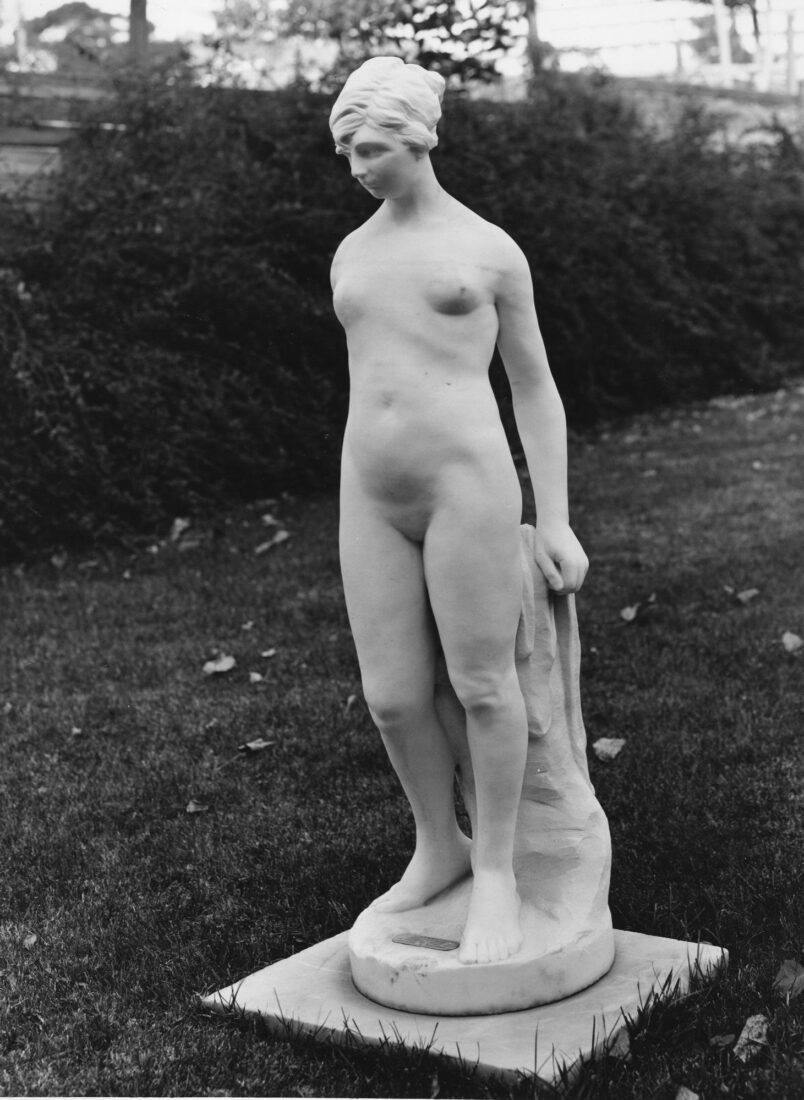

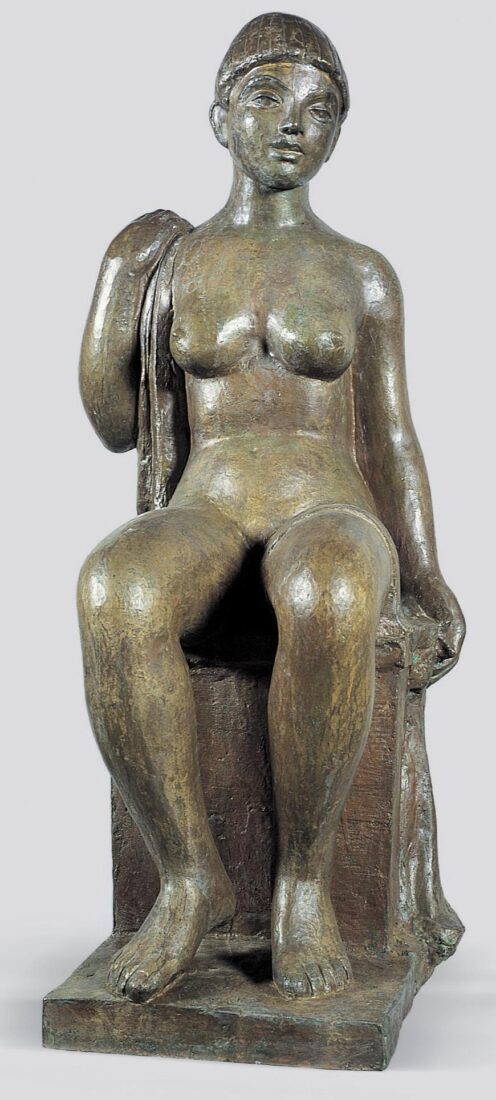

Titsa Chryssochoidi, a student of Thomas Thomopoulos, Thanassis Apartis and the French sculptor Robert Wlerick, belongs among those Greek sculptors who served as conduits par excellence for the style of Aristide Maillol. The female figures, the dominant theme of her work, are usually rendered nude, reclining, seated or half-reclining, with lavish and gentle curves, stable and assured outlines, simple arrangements, a tranquil even languid pose and an otherworldly expression. All these reflect the style of the French artist which Chrysochoidi adopted and adapted to her own perceptions.

The seated “Nude” is an early variation in a smaller scale of a “Nude” which, with a few differentiations, she worked again in 1970 and is on exhibit at the National Glyptotheque.

Titsa Chryssochoidi, a student of Thomas Thomopoulos, Thanassis Apartis and the French sculptor Robert Wlerick, belongs among those Greek sculptors who served as conduits par excellence for the style of Aristide Maillol. The female figures, the dominant theme of her work, are usually rendered nude, reclining, seated or half-reclining, with lavish and gentle curves, stable and assured outlines, simple arrangements, a tranquil even languid pose and an otherworldly expression. All these reflect the style of the French artist which Chrysochoidi adopted and adapted to her own perceptions.

The seated “Nude” at the National Gallery is a characteristic example of her personal style which not infrequently reveals a romantic temperament.