Tranquillity defines “Young Bull” by Nikolas Dogoulis, while the form is stylised and simplified in a way that evokes archaic art – an influence from the years (1963-1967) the artist spent working at the National Archaeological Museum in Athens. Born in Florina and based in northern Greece, Dogoulis drew inspiration from his immediate surroundings, capturing the life and cultural traditions of Macedonia.

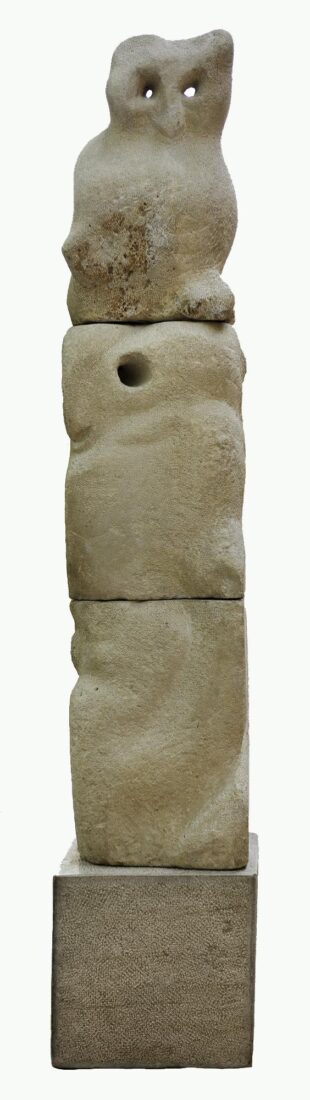

Initially committed to realistic depictions of the human figure since the 1930s – sculpting in plaster and bronze, or carving directly into stone – Bella Raftopoulou gradually moved towards stylisation and simplification, a shift that peaked in the mid-1950s. Her “Owls”, created as she began incorporating animal motifs into her work in the 1950s and carved directly into stone, is the largest and most striking of her animal-themed works. Comprising three separately oriented blocks from which roughly carved owl heads emerge, the sculpture radiates a sense of calm and stillness, as if the birds were roosting in a tree under cover of night.

Yiannis Antoniadis, having studied sculpture at the School of Fine Arts in Athens and architecture in Florence, created works in collaboration with architects, designed public monuments and worked with freely inspired compositions, adapting his style according to the destination and requirements of his works.

In “My Dog”, working in a realistic vein, he depicts his own pet, adopting a naturalistic style with minimal stylisation. Poised and still, with its head extended forward, the dog seems to be alert to something unseen – perhaps awaiting its master, in a moment the artist was eager to immortalise.

Efthymiadi’s engagement with bird forms spanned her entire career, resulting in series of stylised owls, roosters, and eagles in various sizes. Her dedication sprang from a belief that sculpture should be ‘an art that accompanies people in their everyday lives.’ However, in contrast to other thematic units, in which, until the early 1950s, she followed realistic rendering, the birds are characterized from the outset by an abstract mood and stylizations based on a variety of patterns. These characteristics were strengthened after the mid-1950s. From 1955 onwards, she began crafting solid forms from hammered metal, capturing moments of stillness and harmony in works such as “Birds”, where static poise becomes a source of quiet power.

Among Greek sculptors, Frosso Efthymiadi stands alone in her sustained focus on animal subjects. Her dedication sprang from a belief that sculpture should be ‘an art that accompanies people in their everyday lives.’ Small works were intended for interior decoration; larger ones for private gardens or public spaces. ‘I truly love pieces that adorn the garden, and I believe animals are ideal for this,’ she remarked in a 1954 radio interview.

This perception is particularly reflected in the works she created until the mid-1950s in terracotta, following realistic rendering. Thereafter, she turned to metal, forging brass or iron sheets and rods herself. This shift in material accompanied a striking move towards abstraction.

In 1955 she created “Ibex”, her final work in the animal series, which is strongly stylised and decorative. Originally also made in terracotta, the wild goat – of a species native to the mountainous regions of Crete – appears poised on a rocky outcrop, evoking its natural agility on steep slopes.

Efthymiadi’s engagement with bird forms spanned her entire career, resulting in series of stylised owls, roosters, and eagles in various sizes. Her dedication sprang from a belief that sculpture should be ‘an art that accompanies people in their everyday lives.’ However, in contrast to other thematic units, in which, until the early 1950s, she followed realistic rendering, the birds are characterized from the outset by an abstract mood and stylizations based on a variety of patterns.

These characteristics were strengthened after the mid-1950s. From 1960 onwards, inspired by Pre-Columbian metalworking techniques – characterised by the dense soldering of fine gold rods or wires – which she studied during a 1959 journey to Peru and Colombia, she began using hammered brass rods, welded together. In works such as “The Winged Chief”, her largest and one of the most iconic pieces in this style, she seeks to express energy and grandeur through the sudden flare of outstretched wings.

.

Among Greek sculptors, Frosso Efthymiadi stands alone in her sustained focus on animal subjects. Her dedication sprang from a belief that sculpture should be ‘an art that accompanies people in their everyday lives.’ Small works were intended for interior decoration; larger ones for private gardens or public spaces. ‘I truly love pieces that adorn the garden, and I believe animals are ideal for this,’ she remarked in a 1954 radio interview.

This perception is particularly reflected in the works she created until the mid-1950s in terracotta, following realistic rendering. Thereafter, she turned to metal, forging brass or iron sheets and rods herself. This shift in material accompanied a striking move towards abstraction. In this context, the “Animals of the Andes” are stylised depictions of llamas she observed during travels to Bolivia and Peru in 1948, which stand motionless, as though on the high plateaus of their native South American habitat.

Efthymiadi’s engagement with bird forms spanned her entire career, resulting in series of stylised owls, roosters, and eagles in various sizes. Her dedication sprang from a belief that sculpture should be ‘an art that accompanies people in their everyday lives.’ However, in contrast to other thematic units, in which, until the early 1950s, she followed realistic rendering, the birds are characterized from the outset by an abstract mood and stylizations based on a variety of patterns. These characteristics were strengthened after the mid-1950s. From 1955 onwards, she began crafting solid forms from hammered metal, such as “Eagle”, where she seeks to express energy and grandeur through the sudden flare of outstretched wings.

Among Greek sculptors, Frosso Efthymiadi stands alone in her sustained focus on animal subjects. Her dedication sprang from a belief that sculpture should be ‘an art that accompanies people in their everyday lives.’ Small works were intended for interior decoration; larger ones for private gardens or public spaces. ‘I truly love pieces that adorn the garden, and I believe animals are ideal for this,’ she remarked in a 1954 radio interview. ‘You’ll see that all my animals – the little goat, the donkey, the calf, the deer, the foal – are modelled with a realistic spirit, dictated by their intended setting. I sought to capture each animal’s characteristic movement and expression. Every time, I had to bring the live model into my studio. I’d let it roam freely about my garden […].’

Originally modelled in terracotta, her “Calf” embodιεσ this vision. In 1939, Kostas Kotzias, minister for the Greater Metropolitan Area of Athens, commissioned Efthymiadi to decorate the city’s public gardens with terracotta animal sculptures, including “Calf”, destined for Pangrati grove. The project was ultimately halted by the outbreak of war.

In the mid-Thirties, Apartis turned his interest to the making of animal sculpture, studying at the Paris Zoological Garden. Occupied since then, from time to time, with the same subject, in 1955 he made “Female Dog”, using “Duchess”, the dog of a neighbor in Paris, as his model.

The animal, despite the fact it’s motionless, gives the impression of being in a state of complete preparedness, with its pricked ears and muzzle jutting. Guided by ancient art, but having a living model before him as well, Apartis did not expend himself in descriptive details, but moulded a sturdy body with smooth surfaces, under which is outlined the powerful skeleton. The animal’s pose, with its legs parallel to each other, the slight turn of the head to the right and the tail touching the legs, as well as the moulding of the sturdy body itself, bring to mind one of the most important works of ancient art, namely the Etruscan “She-Wolf” in the Capitoline Museum (500-480 BC), while the jutting head had its, albeit distant, model of a dog from the Sanctuary of Artemis in Vravrona (530-520 BC), now in the Acropolis Museum, which, with its body tensed and its legs spread, is ready to attack.

Yannoulis Chalepas was an extraordinarily gifted artist. Yet, his life and career as an artist were branded by the outbreak of a mental illness, which led to his institutionalisation at the mental hospital on Corfu and to a 40-year hiatus in his work. The first symptoms of a deviating behaviour became manifest in 1878, at which time the first period of his creative production came to an end.

During that period, Chalepas was thematically inspired by the Greek Antiquity and mythology, in accordance with the neoclassical spirit which prevailed in 19th-century Greek sculpture. “Satyr Playing with Eros” is a characteristic work in this respect. It is, moreover, the first of 12 related works made by the sculptor.

In this first variation, Chalepas created an open, multi-axial composition of vivid motion, reminiscent of Hellenistic art, able to be viewed from multiple points, characteristic of his work in general. Neoclassical elements can be identified in the nudity of the figures, the rendering of the eyes without pupils and irises, as well as in the soft, almost impeccably polished surface of the marble, which enables the light to glide smoothly. The tender body of Eros is projected upon the shadow of the Satyr’s breast. Contrary to many images depicting satyrs as repugnant old men, Chalepas chiselled the figure of an adolescent, whose dual nature is only evoked by a short tail at the base of the spine, the pointed ears and the two small horns, which can barely be seen high on the forehead.

The first effect created by the work is of a joyful scene, full of innocence and insouciance. Yet, upon a closer look, it becomes apparent that the Satyr’s grin is a mocking one, and his expression is cruel and disparaging. It is in vain that little Eros is trying to reach for the grapes.

What is evoked here for the first time is the sculptor’s relationship with his father. Chalepas’s father had been opposed to his son’s artistic vocation right from the start. From 1918 until 1936, Chalepas made 11 more works on the theme of Satyr and Eros in clay or plaster. These works reflect Chalepas’s gradual liberation from the tyrannical figure of the father.

The work is inspired by C.P. Cavafy’s poem “Artificial Bloom”

C.P. CAVAFY

Artificial Bloom

I do not want real narcissi – neither lilies

Nor real roses appeal to me

They only adorn platitudinous and common gardens

Their flesh inculcates bitterness, weariness and grief to me

Their perishable beauty bores me

Give me artificial blooms – glories of porcelain and metal –

That do not wither and rot, with images that do not age

Blooms of the marvelous gardens of another land,

Where Theories, Rhythms and Knowledge reside

I love blooms made of glass or gold,

True gifts of faithful Art

Painted with colours more lovely than the natural,

Elaborate with nacre and enamel,

With ideal leaves and branches

Their grace taken from wise and purest Elegance

They did not grow dirty in dust and mud

If they have no scent, we shall pour fragrance

(And) We shall burn sentimental scents before them

Translated by Yannis Kaloudis

from the exhibition catalogue

C.P.Cavafy “Pictured”. 40 Contemporary Greek Creators

Yannoulis Chalepas was a uniquely gifted artist. But his life and artistic development were marked by the manifestation of mental illness that led to confinement in a psychiatric hospital on the island of Corfu and a forty-year hiatus in his artistic production. The first symptoms of aberrant behavior presented in 1878, the same year that he completed his first body of work, referred to by historians as the “first period.”

The “Sleeping Female Figure” is Chalepas’ most widely known sculpture. The original composition was created in marble for the grave of eighteen-year-old Sofia Afentaki in the 1st Cemetery of Athens.

Chalepas based his depiction of the dead girl on the convention of the supine or reclining figure on a sarcophagus or bed. This image originated in ancient Etruria and was particularly popular in European sculpture. Chalepas, however, eschewed total rigidity by flexing the figure’s leg and slightly turning her head. The plasticity of the flesh and the different fabric textures render the work especially lifelike. The girl has a tranquil expression on her face. With her closed eyes and parted lips, she appears to be in a state of abandoned, peaceful sleep. Her pose is completely natural and the drapery folds are executed with exceptional skill. The sole feature evoking the world of the dead is the cross she holds at her breast. This feature connects the work to Greek antiquity as well as to classicistic notions. In ancient Greece, Hypnos (Sleep) and Thanatos (Death) were twin brothers. Neoclassicists saw death as an eternal dreamless sleep.

This cast of the sculpture was made in 1980 in the workshop of the National Archeological Museum. It was an initiative of the then director of the National Gallery Dimitris Papastamos and the mayor of Athens Dimitris Beis in an effort to save certain important neo-Hellenic sculptures from deterioration due to extended environmental exposure.

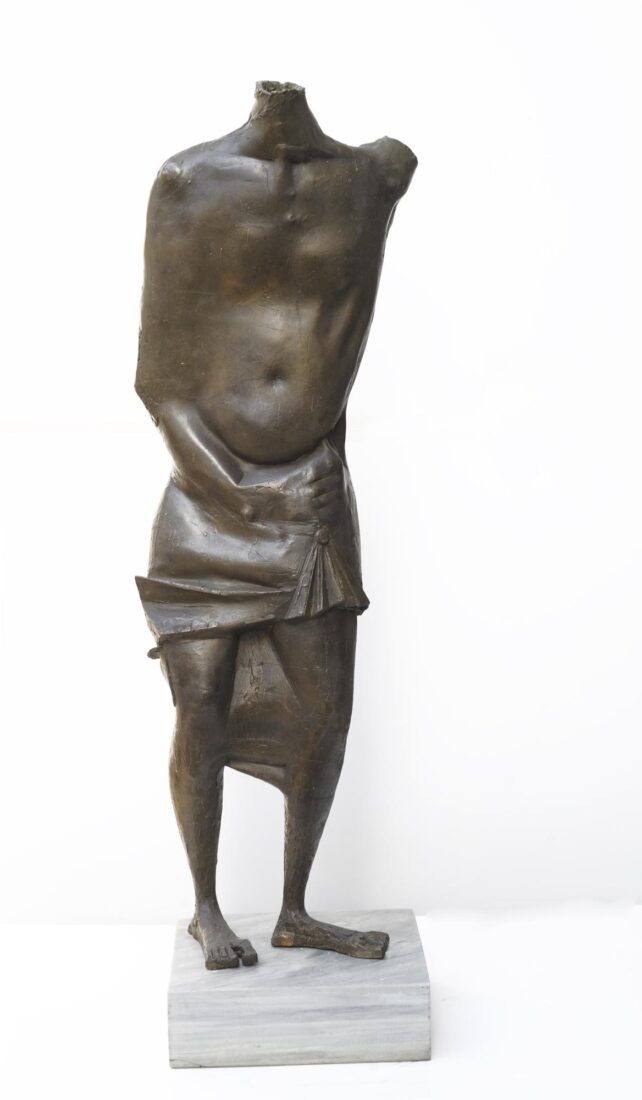

Apartis made this relief stele in response to a commission for a monument to the Boy Scouts of Smyrna, who had been tortured during the Asia Minor Disaster. But in the end the memorial was not approved by the commissioners because it depicted a naked male figure. In 1983 the relief, incorporated into the copy of the iron door of a cell, was used for the composition of a monument in honor of the patriots who were tortured during the German Occupation, in the holding cells of the Gestapo. The composition also bears the titles “The Prisoner”, “The Martyr”, “The Victim”, “On Execution” and “So the Land You Walk upon Will be Free”.

Apartis, wanting to make a work that would symbolize all the young men who sacrificed themselves for an ideal, combines elements from Maillol’s “Bicyclist”, from ancient funerary steles, as well as the inclination of the head which, in works by Michelangelo, Rodin and Bourdelle expresses inner anguish and death.

“The Healer” is one of the eight pictorial images that surrealist painter Rene Magritte “translated” into three-dimensional form.

Magritte had a precise idea of what he wanted to achieve and went about finding the ideal means to execute these sculptures. For “The Healer” he made a plaster cast from the feet of a live model, and did the same for the bird cage.

“The Healer” has a number of features characteristic to Magritte’s enterprise, including the element of the unexpected, the extraordinary within the ordinary, and the mysterious. This sculpture, variations of which can be found in at least four of his paintings, came from a photograph that Magritte took in 1937, titled “God on the Eight Day”.

Although he was a painter, by translating eight paintings into sculptures, Magritte provided a different perspective on the function of objects and forms. Detached from the confines of the picture plane, they are placed in the space as autonomous presences and, through the change in scale, become different entities.

The full-length male figure, heir to the ancient Kouros, dominates Joannis Avramidis’ oeuvre. However, his is a figure that is stripped of every descriptive detail. Schematized, it stands upright, self-contained, imposing and static, like an ancient column.

The solitary figure-standard, as of 1959, constituted the core of his group compositions. The figures create a unit and frequently result from the revolving of the ancient figure around its axis. In this manner, Avramidis conveyed the idea of the ancient Greek “Polis” (City-State) in his sculpture of the same title. The repetition of the ancient figure nine times creates a compact group of identically-sized figures with like features. The piece thus personifies the idea of a community in which all its citizens are equal.

Dionyssis Gerolymatos is one of the few sculptors still working in the traditional sense, that is, he works with hard materials – stone, marble, cement. His thematic field includes works taken on commission as well as compositions of free inspiration, small or large. Since his student years, he has made use of extreme schematization, which, in his later works, is sometimes transformed into abstraction. Employing an expressionistic or surrealistic style, he gives form to thoughts, feelings, and impressions, while frequently poetry is also a motivation behind compositions through which he illustrates verses.

The “Stone of Patience” is a characteristic example, where a line from George Seferis is taken as the title of a work, while other of the poet’s verses are engraved on the side. Using stone, a hard material, Gerolymatos combines the external volume, left deliberately rough, with a piece ground smooth which then takes on the schematic form of a bird with open wings – symbol of freedom and hope – and thus creates his own image, an optimistic one, for the poetic words.