“The First Steps” is one of Iakovidis’ best-known and loved works. The scene is set in a Bavarian village home interior, bathed in the light pouring through the open window. Dressed in dark cherry tones, the grandmother is holding the blond baby, full of courage and smiling, taking its first steps in the world, on top of a wooden table. The grandmother has left her red knitwear in a corner. Note this dash of red colour in Iakovidis’ works; we have also seen it in his teacher, Nikephoros Lytras’ paintings. The baby’s elder sister, seated with her back towards the foreground, is waiting to receive the baby with her arms open in a protective gesture. Note also the effect of the light on figures: All white and blond, the baby is dazzling. It thus becomes the symbol of emerging new life. The incoming light, on the contrary, illuminates the girl’s outline, lining it with a bright aura. The work exudes life and elan vital.

First shown at the Glaspalast exhibition in Munich in 1892, this painting marks a key change in Iakovidis’ work regarding his interpretation of light. The natural light floods the scene as it comes through the window, adding vibrancy and ambiance.

The “Children’s Concert” is one of Jakovides’ boldest works with respect to technique and lighting. The merry scene is set in the bright interior of a Bavarian village home, lit up by two windows, one on the left and one in the centre. These windows doubly illuminate the scene, and the light entering in two opposite directions poses a problem, which the artist resolves masterfully as we shall see. But let us first meet the characters: the four young musicians. The first one, seated, is playing the drum, the second is straining in order to blow into the trumpet, the third one, half-hidden, is probably playing the harmonica, and the fourth one, standing further on the side, in lack of a proper instrument, is blowing hard into a bright red watering bucket. All the children are barefoot. Which is the audience of this children’s concert? The mother, seated on the left, close to the window, but mainly the little sister, her arms extended towards the musicians. Another older sister is seated in front of the main window, full of flowers. The painter is “watching” the scene from above, which is why the floor boards have been drawn in perspective.

The protagonists in this musical, vibrant feast, are light and colour. The entire scene is bathed in orange hues, which become even bolder as the painter places their complementary colour, blue, adjacent to them. The light comes from two opposite directions, making the volumes of the children dark and heavy, whereas the outlines are intensely illuminated. Thus, the first boy’s shirt becomes almost transparent. The face of the elder girl has “melted” into the light. Here, Iakovidis pushes his art to the extreme, in other words, Impressionism.

This work has been painted in two versions. The earlier one was first shown in 1896, during the first Olympic Games in Athens. Its colours were on the cool, grey side, as Emmanouil Roidis remarked. Iakovidis repeated the painting in order to send it to the 1900 Paris World Fair, where it earned a prize. This brighter version is the one we are now able to enjoy at the National Gallery.

The dramatic scene depicted in this painting is set in front of the sanctuary gate in the interior of an Orthodox church. The church has suffered great vandalism and sacrilege by the Turks; it has been robbed of its sacred utensils, seen piled up on the floor. Yet, the protagonist is the beautiful, almost naked Greek girl tied on the church bench. Her face conveys pain, outrage, anger.

The scene has been painted with the characteristic accuracy and mastery of French academic painting, seriously influenced by photography. The red belt is the only bold colour in this painting, in which brown tones are dominant.

Despite the fact the artist was then unknown and the work in poor condition, this painting was purchased by the National Gallery in 1952 for the aesthetic value with which it is so fully imbued. In 1978 Cesare Brandi, in an article he wrote for The Burlington Magazine, attributed this work to Gentile da Fabriano and dated it to around 1418. Then Roberto Longhi and Federico Zeri attributed it to Zanino di Pietro while Keith Christiansen, who agreed with their attribution, dated it to around 1405-1410.

Many of his works, such as the one at the National Gallery, have been attributed to Gentile da Fabriano, which points to the influence these two painters had on each other, while the influence of Michelino da Besozzo, who worked in Venice until 1410, is also obvious. The Virgin Mary with Divine Infant and Angels (a subject often found in the works attributed to this painter) is characterized by the elegance and charm of its late-Gothic style. Following an iconographical method very widespread at the end of the 15th and the beginning of the 16th century, Madonna dell’Umilta, in which the Virgin Mary is depicted sitting on the ground, the Virgin Mary in this rendition is painted in a flowering field and holding the Divine Infant on her knees. On their artistically rendered halos can be very easily read the inscriptions: Santa Maria Mater Dei for the Virgin Mary, and Jesus Nacarenum rex Judeorum for Christ. On the left their hands are joined in a complex unity with the stem of a flower (today destroyed) which must have been a rose, symbol of both the Virgin Mary and the Divine Passion. Surrounded by five angels, done on a smaller scale, we see the two on the right in an attitude of prayer, a third stretching his arms in praise to the heavens, while the other two, at the bottom of the painting, are gathering flowers.

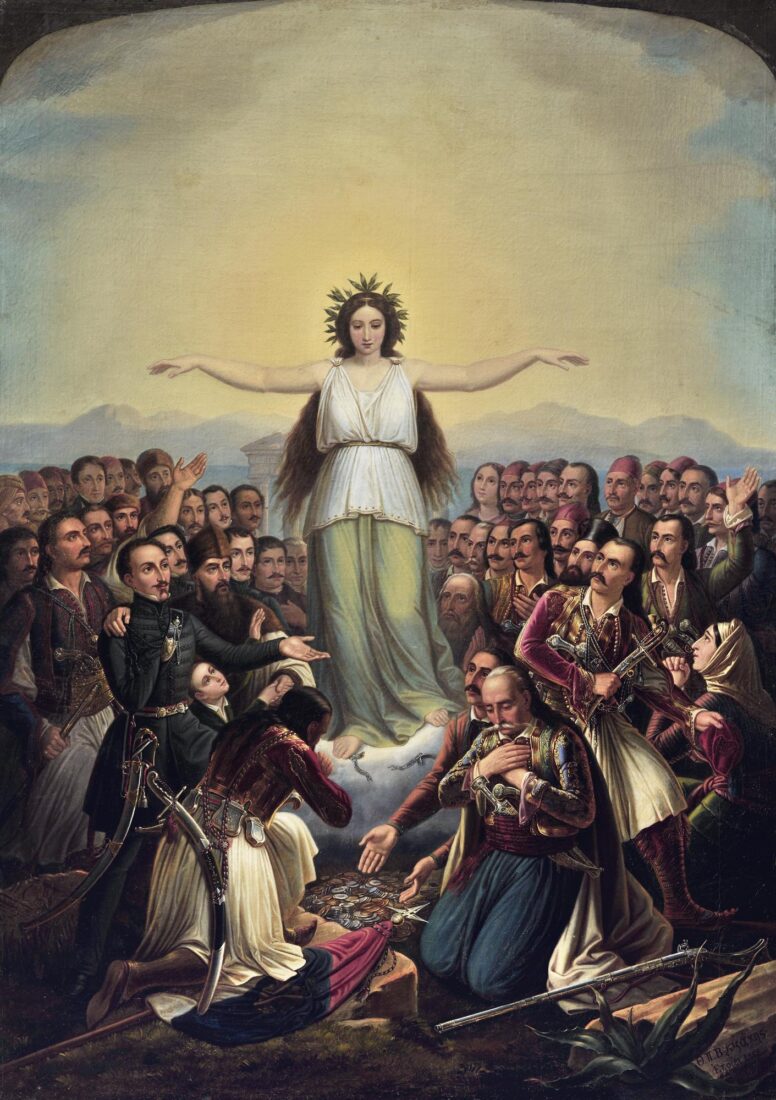

This painting depicts the army camp of General Karaiskakis at Phaliron during Greek preparations to capture the Acropolis, besieged by the Turks, in April 1827. Greeks and philhellenes are arranged along a section in the foreground, while in the mid-ground on the right, the eye is guided towards the hill from which the leading officers of the army survey the battle field. In the background on the left can be seen the Acropolis. Almost in the centre, a Greek is leaning against an ancient marble in an allusion to the heritage of classical Greece. On the right, a priest is blessing the fighters. The officer in the blue uniform on the left is Bavarian philhellene Krazeisen, to whom the Greeks are grateful. He captured for posterity the figures of the 1821 freedom fighters as we know them today. It is from these drawings that Vryzakis sourced the portraits of the fighters on the hill: Karaiskakis, Makrygiannis, Tzavelas, Notaras, the Scot named Gordon, Englishman Hastings and Karl von Heideck, looking towards the Acropolis through a telescope. Heideck, who had first-hand experience of these events, painted the same subject, and Vryzakis quoted his painting much later, in 1855. The Greek flag sways on the top right. The gold-red and brown colours characteristic of Vryzakis’ work are also pre-eminent in this painting. The description blends tension and suspense with release provided by charming genre interludes.

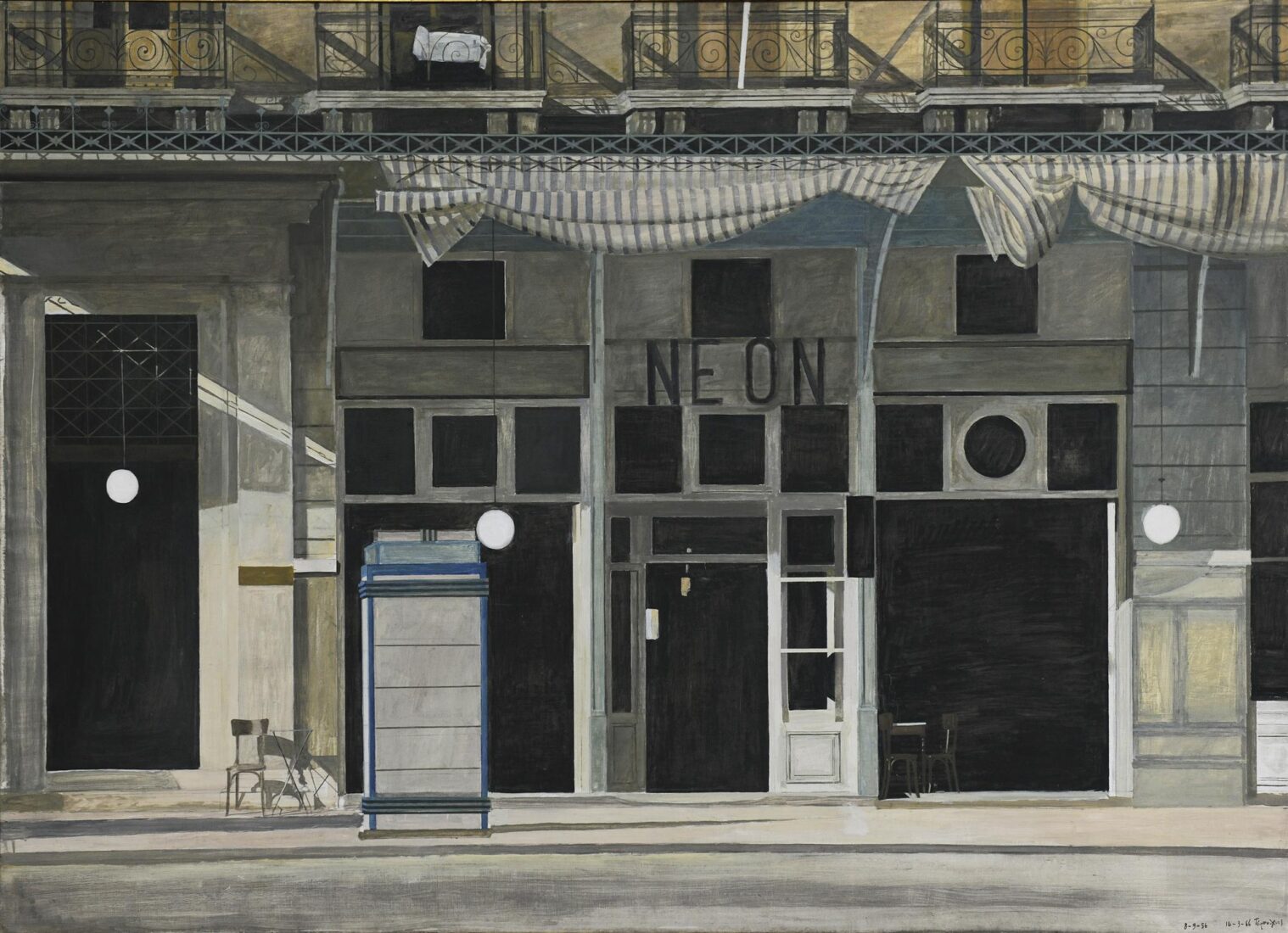

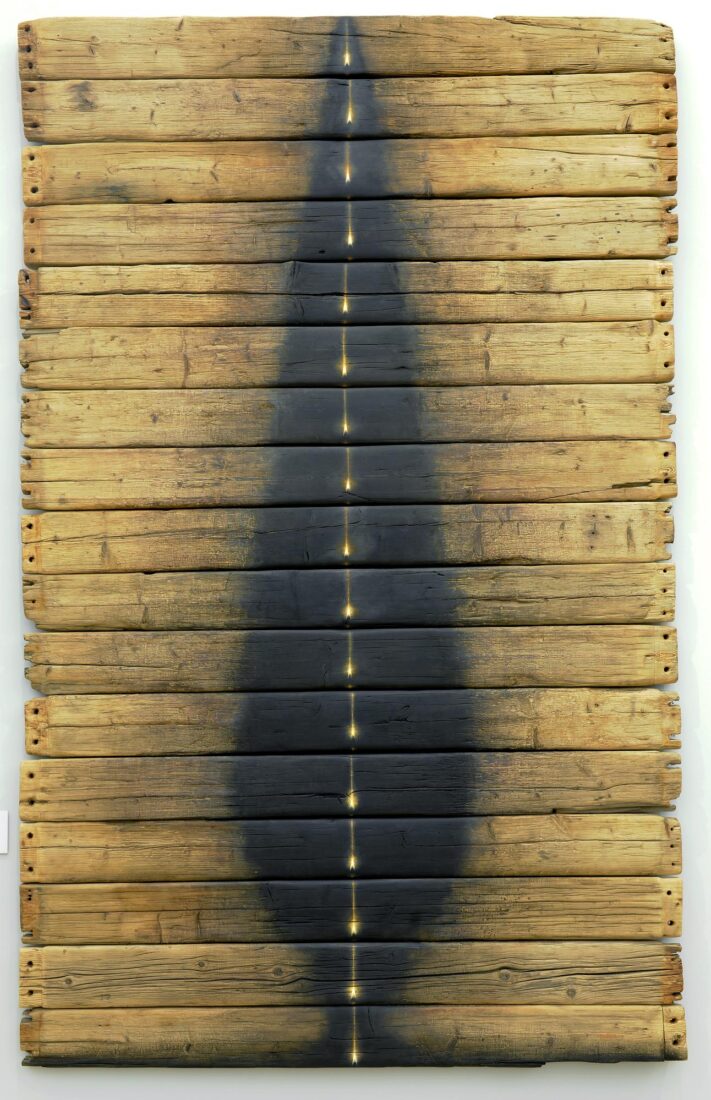

Christos Bokoros is one of a group of younger artists who returned to figurative painting, but with a renewed eye, in pursuit of a new meaning in the image. Bokoros is an explorer of memory. He is excited and moved by the traces that human life leaves behind – its labors, its pain, its joy and its hope. The life that has departed leaves behind anonymous imprints that the artist extracts from obscurity and silence to gives them new meaning. The materials he uses in his work bear the obvious signs of use and age: wood recovered from submerged slips, old boats, tables, rusted remains of vessels hallowed in human hands. On these materials, as on an altar, Bokoros reverently deposits his image. It is telling that the flame is the iconic image of his practice: a flame of a candle, a flame of a lamp, a humble flame symbolizing memory. It is the perpetual flame that burns before icons, the candle lit on Greek Orthodox Easter, the promise of eternity that exorcizes corruption.

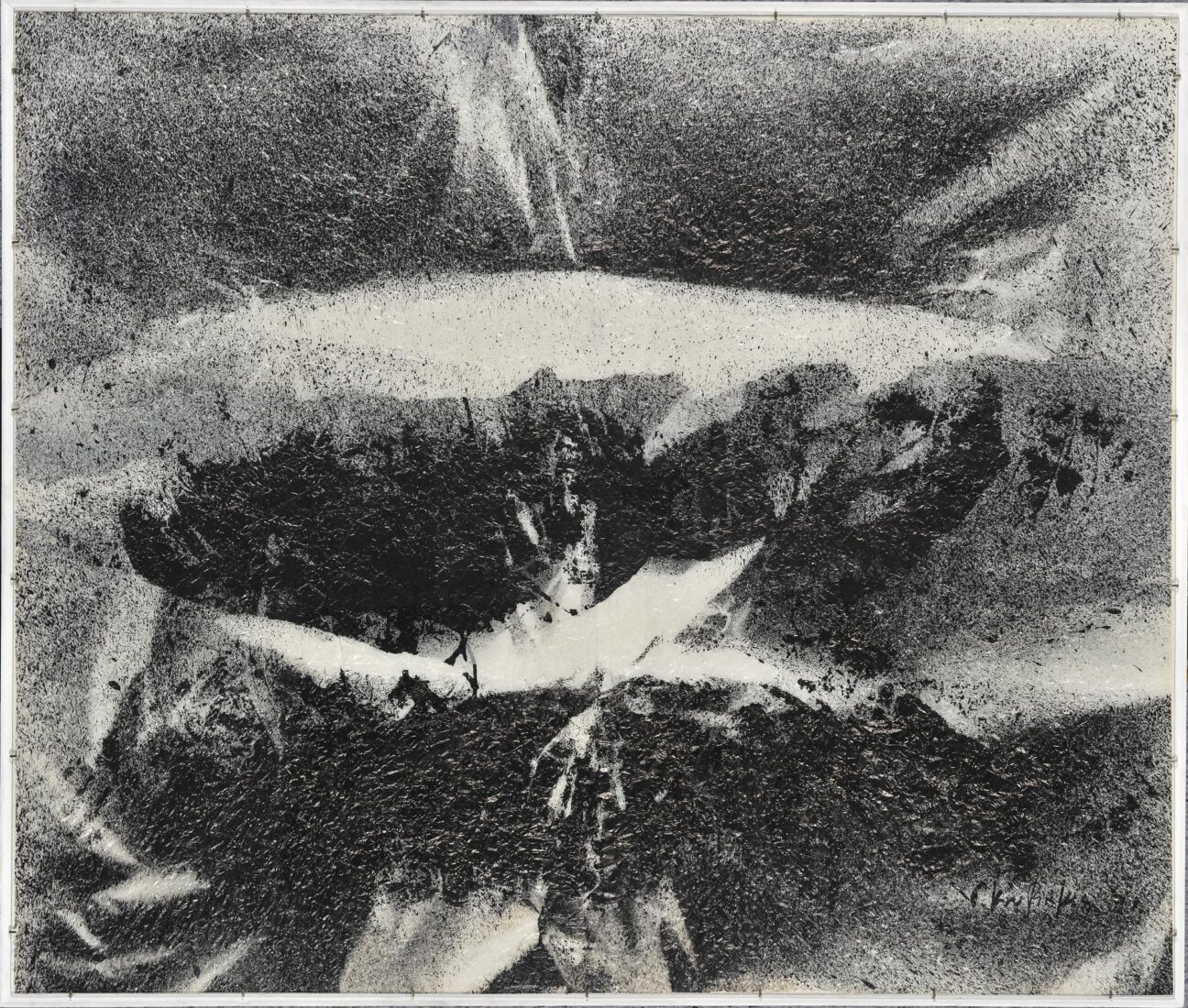

The Enigma of Parrhasius is an allegory. It narrates a story of painting, the adventure of form from Antiquity to contemporary art: the stormy seas it has weathered, the questioning it has undergone, and the painter’s faith in is endurance and survival.

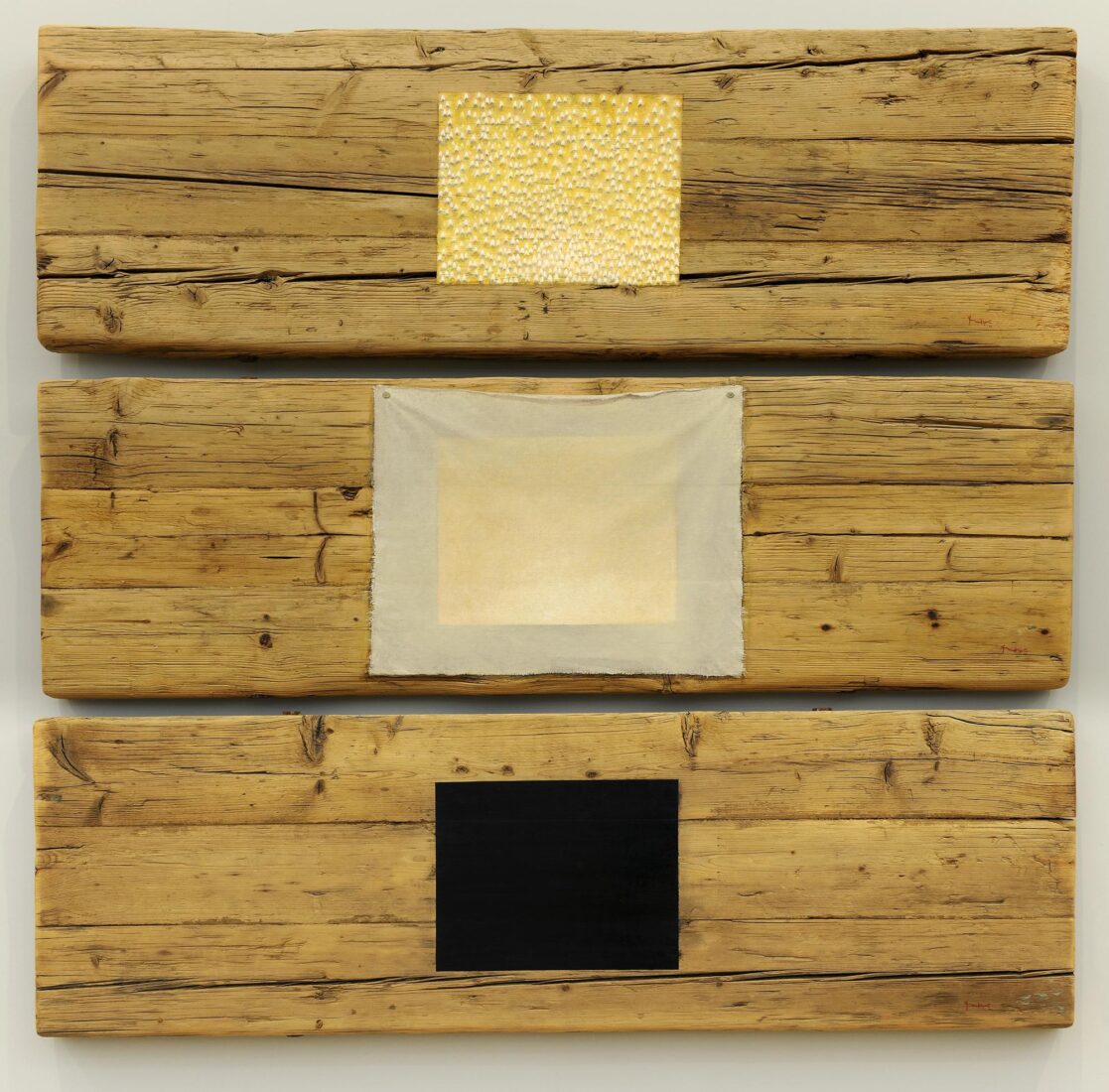

The narrative unfolds in a triptych. Three horizontal weathered wooden boards, salvaged from an old bridge, are placed parallel to each other, ready, after suitable preparation, to receive the painted image. The first panel depicts a black square: a reference to the famous painting by Russian artist Casimir Malevich. At the time when this, the quintessential minimalist work of Suprematism was made in 1915, philosophers and critics rushed to pronounce the death of painting. The second panel leads us to a well-known incident told by Pliny the Younger (1st century AD), recounting two famous painters of classical antiquity who lived in the time of Socrates. Zeuxis and Parrhasius were competing, as was the custom in those days, for the honor of most perfect painter. This was the age dominated by the notion that imitation and perfection equaled verisimilitude. Zeuxis painted a basket of grapes so vivid that the birds were fooled and began pecking at it. Parrhasius chose to paint in a very illusionary manner a drape that supposedly covered his painting. When Zeuxis ordered him to remove the drape to unveil what he’d painted, Parrhasius replied triumphantly, “You succeeded in fooling the birds, but I have tricked the great painter Zeuxis. Therefore I deserve the title of victor.

In the second panel of the triptych, Bokoros has painted a piece of cloth on the square with such skill that it appears real. But behind in glimmers an imperceptible light. In the third panel the cloth has been removed to reveal a square field flowering with little flames. The message of the piece is clear: painting as it travels through time it can weather storms and be questioned, but in the end it always emerges the victor.