This painting, originally entered in the archives of the National Gallery as a work by Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, was later attributed to Cecco del Caravaggio by Roberto Longhi. The identity of the painter called Cecco del Caravaggio was unknown. He was believed to be alternately French, Spanish, even Dutch, whereas Gianni Papi identified him as the Italian Francesco Boneri (G. Papi, “Cecco del Caravaggio,” Nuova Memoria, Florence, 1992).

Cecco del Caravaggio (Cecco is short for Francesco) worked in Italy during the first half of the 17th century. Mancini, in “Considerazioni sulla Pittura”, c. 1620, refers to a Francesco, called del Caravaggio, as an admirer and imitator of Caravaggio. It seems that the high regard Francesco had for the Lombardian painter, and his ability to imitate the master, gave him the pseudonym del Caravaggio.

This painting has generated much debate over its content. Roberto Longhi chose the title “Musical Instrument Maker” on the basis of the round object that the young man holds in his hand, which he seems about to place on the tambourine. Besides the violin – and it’s unclear whether this has been constructed or simply repaired – there is nothing else to indicate an association with this occupation. Furthermore, the array of objects in the foreground, which, aside from the violin, have nothing to do with music, heightens the mystery surrounding its theme. The painting’s enigmatic and allegorical character allows us to speculate that it was directed towards connoisseurs – a reason why A. Cottino chose the title “Allegorical Portrait of a Youth with Musical Instruments” (A. Cottino, “La natura morta caravaggesca” in “La natura morta in Italia”, vol. II, p. 726).

On the occasion of the publication of the work in the 2018 Calendar, in the introductory text, the director of the Athens National Gallery, Marina Lambraki Plaka, commenting on the painting, proposes the title Young Musician in a Workshop of Musical Instruments or Allegory of the Five Senses”: “The work was originally, and for many decades, known under the title given by the eminent Italian art historian Roberto Longhi: Musical Instrument Maker. Under this title, it was featured in many international exhibitions. The young man’s sumptuous dress, however, the feathered hat, and the carnation behind the ear, his noble features, as well as his placement in the composition, preclude this identification. Craftsmen are commonly seen in contemporary paintings and accounts of the time to wear casual, worn-out clothes, leather aprons, and their rough figure often betrayed their low-class origin.

The young nobleman is seated on a luxurious chair, with a high backrest, behind a bench or table, with open drawers that face the viewer. This was a common artists’ device aimed at making the viewer identify with the invisible interlocutor of the depicted figure. But what is the identity of the figure that does not appear in the painting? A musical instrument dealer? In this case, his young patron is offering him a coin in his left hand as payment for the tambourine in his right. A musical dilettante who was also a musical instrument collector? We may never know. What about the objects scattered on the bench, masterfully painted in illusionistic verisimilitude? A violin, a small telescope, hastily folded document scrolls, empty round boxes, and a wine carafe. Let’s attempt a new interpretation here: Whatever the thematic pretext, this enigmatic scene may be an allegory of the five senses: the musical instruments, the inaudible sound of the tambourine and of the song suggested by the boy’s half-open mouth all evoke the sense of hearing; his left hand, holding the coin, denotes touch – as does the feather that adorns the young man’s hat; the small telescope and the painting as a whole are a celebration of sight; smell is suggested by the carnation – that explains why the fragrant flower was introduced, placed behind the young man’s ear. The wine carafe, finally, is a tribute to the fifth sense, taste. This is how the mystery of the juxtaposition of such disparate objects in this captivating painting can be solved.”

Gianni Papi dated this painting to the mid-1620s. A second version of the picture with some variations mostly in the garments, the facial expression and the position of the musical instrument held by the youth, is in the Wellington Museum in London.

This painting is attributed to the school of Bernard van Orley and in particular to the studio of his student and partner Pieter Coecke van Aelst. Coecke had a very active studio in Antwerp with many commissions for paintings and for designing tapestries. The great demand for paintings by the church and the nobility, a result of the Catholic Church Counter-Reformation efforts to prevail against Protestantism, led to an increased production, focusing mainly on the subject matter of the Madonna, the Holy Family and the Adoration of the Magi.

The National Gallery work perhaps follows the original composition of Bernard van Orley, which was reproduced in several versions (at least 11 are mentioned), with differences by Coecke’s studio mainly in the background. The composition is quite compact and comprehensive in its organisation and incorporates in a relatively small area the figures of the Madonna, the Holy Child, Joseph and an angel, who hovers above and crowns the Madonna.

The Virgin Mary, holding an apple, is presented as an alternative Eve, a saviour of the world from the original sin through the baby she holds on her lap, while Joseph offers Jesus a pear, a symbol of the divine incarnation. The composition includes a still life in the bottom-right foreground with apples and pears and their corresponding symbolism, walnuts representing the flesh of Jesus Christ and grapes referring to his Sacrifice.

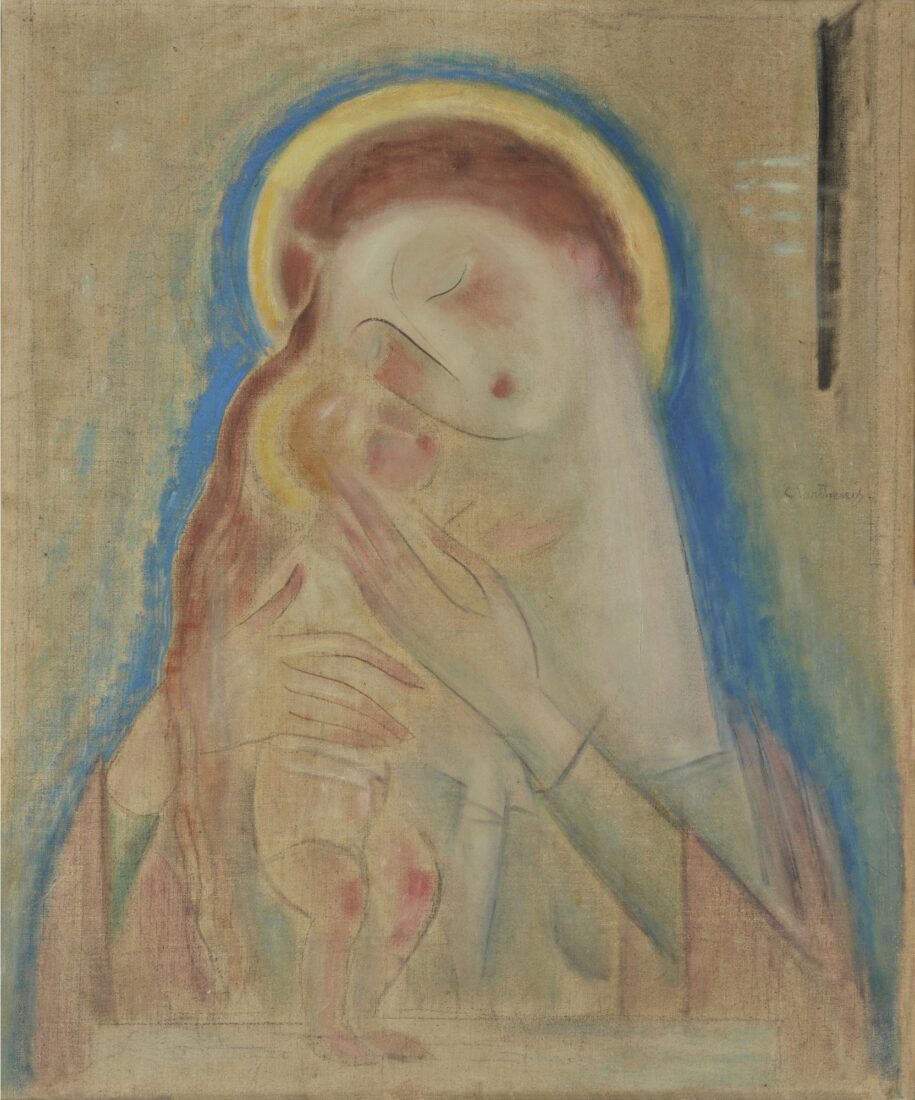

The Madonna, and all she symbolises, was a prominent figure in the oeuvre of Konstantinos Parthenis throughout his career. This work, which has a particular significance, may be placed somewhere between the beginning of 1930 and early May 1935, and it carries the painter’s own touching dedication to his daughter for her birthday on 9 May on the back of the canvas: My dear Sophia,/ for your 21st birthday please accept and keep safe for ever/ this Madonna who with her immense / affection will also always keep you safe/ your father/ K. Parthenis. The back of the canvas displays further information about the work and its story. The labels on the frame, for example, attest that the painting left the house of the Parthenis family to be exhibited at the XXI Venice Biennale in 1938 (cat. no. 373).

The “Madonna and Child” also demonstrates the progression of Parthenis’ painting. From the beginning of the 1930s, he had already reversed the canvas, painting not on the side covered by white-toned primer but on the bare side of the linen fabric, thus conveying the sense of an immaterial, active ‘space’, inhabited by pencil lines, infinitesimal stripes, faint brushstrokes of varying lengths and delicate tones. This is how Parthenis’ impressive wealth of distinctively fine colours emerges. He played with ochre, thick red and blue, creating something of a musical composition that defines what is sky or celestial presence, whilst bringing to the forefront the tender relationship between mother and Holy Child, father and daughter, the capacity of painting to infuse the divine into the human.

This painting is a variation of a work by Paolo Caliari (better known as Paolo Veronese), which is in the library of the Ateneo Veneto (Istituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti in Venice). The Ateneo Veneto is a non-profit institution that was founded in 1812 and is housed in the building of the Scuola Grande di San Fantin, also known as the Scuola di Santa Maria e di San Girolamo. In 1562 a number of great architects, painters and sculptors, amongst them Veronese, embarked upon a major reconstruction and decoration scheme for the Scuola, which had been destroyed in a fire. This date also defines the period during which this composition was created, that is to say, after 1562 or possibly in 1563, a time when religious painting followed the edicts of the Council of Trent (1545- 1563), which issued condemnations of what was judged as heresy committed by Reformation Protestants. In its final session, in 1563, the Council delineated the rules for religious images: they were to undertake the role of the ‘book for the illiterate’ and had to be comprehensible to the faithful and approved by the bishop.

“The Adoration of the Magi” is an image that is readily understandable. The Holy Family is placed off-centre, on the left side of the composition. The Virgin Mary, with the Christ Child in her arms, is sitting on the steps of a magnificent building and extends Jesus’ tiny foot to the first magus to kiss. Joseph, on the very left, with his side and back to the viewer, is helping and at the same time protecting them. Behind the kneeling magus follows a second, while the third is not completely visible. The protagonists are surrounded by horses and soldiers, while two servants in the foreground hold the gifts.

In comparison to the Ateneo Veneto work, the National Gallery painting is different in several ways, mainly in size. Although the National Gallery work is larger, a substantial part from the right side of the composition is missing, as well as a part from the left. In addition, the many over-paintings prove that it has suffered damage in the past. In the recent attempt to conserve it, the removal of a large part of the over-paintings, mainly from the cape of the magus, revealed a refined, albeit chromatically dull brushstroke. The painting’s quality, however, leads to the conclusion – with all due reservations – that this is a version of the Ateneo Veneto work created if not by someone from the studio of Veronese, then by someone close to his time who followed his example.

The story of Susanna and the two old men who watched her while taking her bath, her trial, based on the false accusations by the old men for adultery, because she had rejected their advances, and her acquittal with the help of the prophet Daniel, were all very popular depictions of the triumph of purity. Becoming a symbol of spousal fidelity from the 16th century on, this was yet another pretext for depicting the female body in a nude, yet decent pose. Susanna and the Elders, donated to the National Gallery by Georgios Averoff, is an example of this iconographic theme, credit for which is hesitantly attributed by Marilena Cassimatis and Angela Tamvaki to the Dutch artist Adriaan van der Werff (Kralingen, 1659 – Rotterdam, 1722).