The painting illustrates an excerpt from Virgil’s Idylls (X. 69) which lauds the invincible power of Love (Eros): “Amor vincit omnia et nos cedamus amori”. The painter had recourse to the figure of a winged youth, holding a bow in his hand, the characteristic symbol of Eros (Cupid). The apparent indigence of the young man, who is presented naked and who is turned facing the viewer with his melancholic and, at the same time, sarcastic gaze, is in stark contrast to the wealth of objects that surround him: an enormous harp, the carved suit of armor, the books and musical instruments, the astrolabe, the sculpted head and a painter’s palette; all objects which signify worldly satisfaction and human knowledge which Eros disdains and enslaves with his passion. This type of allegorical presentation, the ambiguity of which is one of its most charming features, was in great demand by aristocrats and the more exalted prelates of the Roman Catholic Church at the beginning of the 17th century. Eros Triumphant, done by Caravaggio for the Marquis Vincenzo Giustiniani in Rome in 1601-1602 (Berlin, Germaldegalerie), not only made an enormous impression of the art lovers of the time but also gave rise to a frenetic competition between the imitators and the adversaries of the Lombard painter Giovanni Baglione who, in 1603, took Caravaggio to court and several of his friends, and who painted for Cardinal Benedetto Guistiniani, brother of Vincenzo, two versions, moralistic in character, of the same subject, Eros Triumphant, incorporating the figures of Celestial and Terrestrial Eros (1602, Berlin, Germaldegalerie and Galerie Nationale di Palazzo Barberini, Rome).

Several years later depictions of Eros triumphant made their way to the forefront again as they were sought after by Tuscan collectors. The composition of the work at the National Gallery has many points in common with the Caravaggian model, the main difference being that the youth is staring straight ahead and the rendering is more restrained. The stylistic perception governing the work is related to that of Florentine painting from 1620-1630.

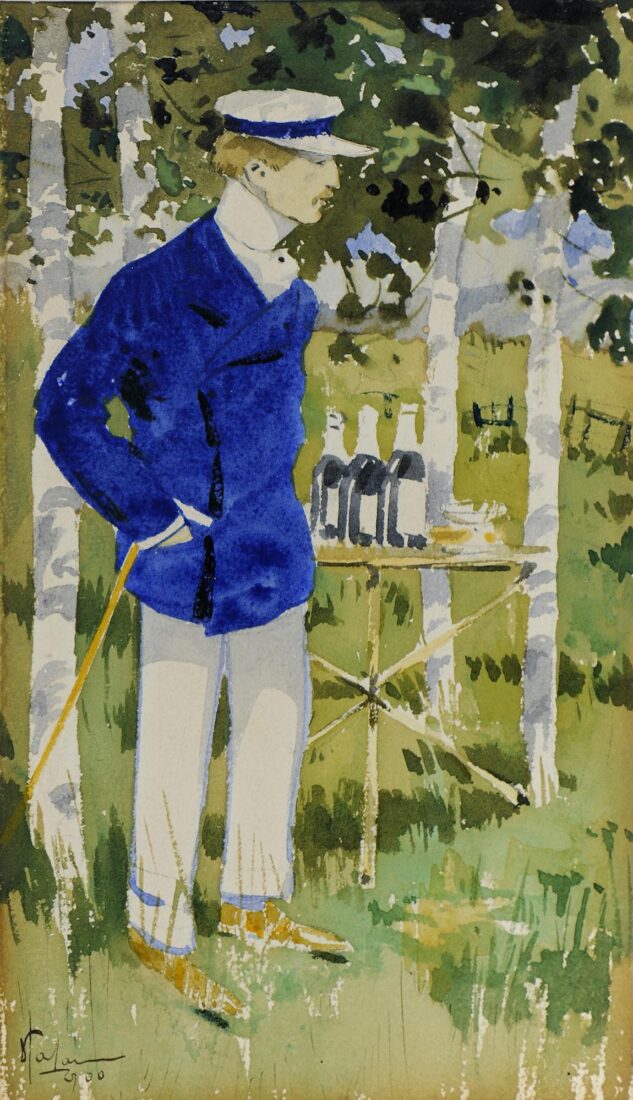

Iakovidis is the last great exponent of the Munich School. Although he distinguished himself in many genres (genre painting, portraiture, still life), he was mainly known and loved by the people as a painter of childhood. Most of his works on this theme were painted in Munich, where he lived from 1877 to 1900, when he was invited to return to Greece and become the director of the National Gallery, which had only recently been established. Iakovidis inimitably captured the relation of the elderly, grandfathers and mothers, with their grandchildren.

This work features a dark-clad goodly grandmother, holding a cute blonde little girl in her lap; the child is wearing a white flowery apron and red socks. The bronze fruit plate has captured her attention — a great opportunity for the artist to create a wonderful still life. The scene unfolds against a white wall, contrasting sharply to the dark-coloured main subject. Everything has been painted with an extraordinary knowledge of drawing, colour, light as well as profound insight into the psychology of the relation between the two ages.

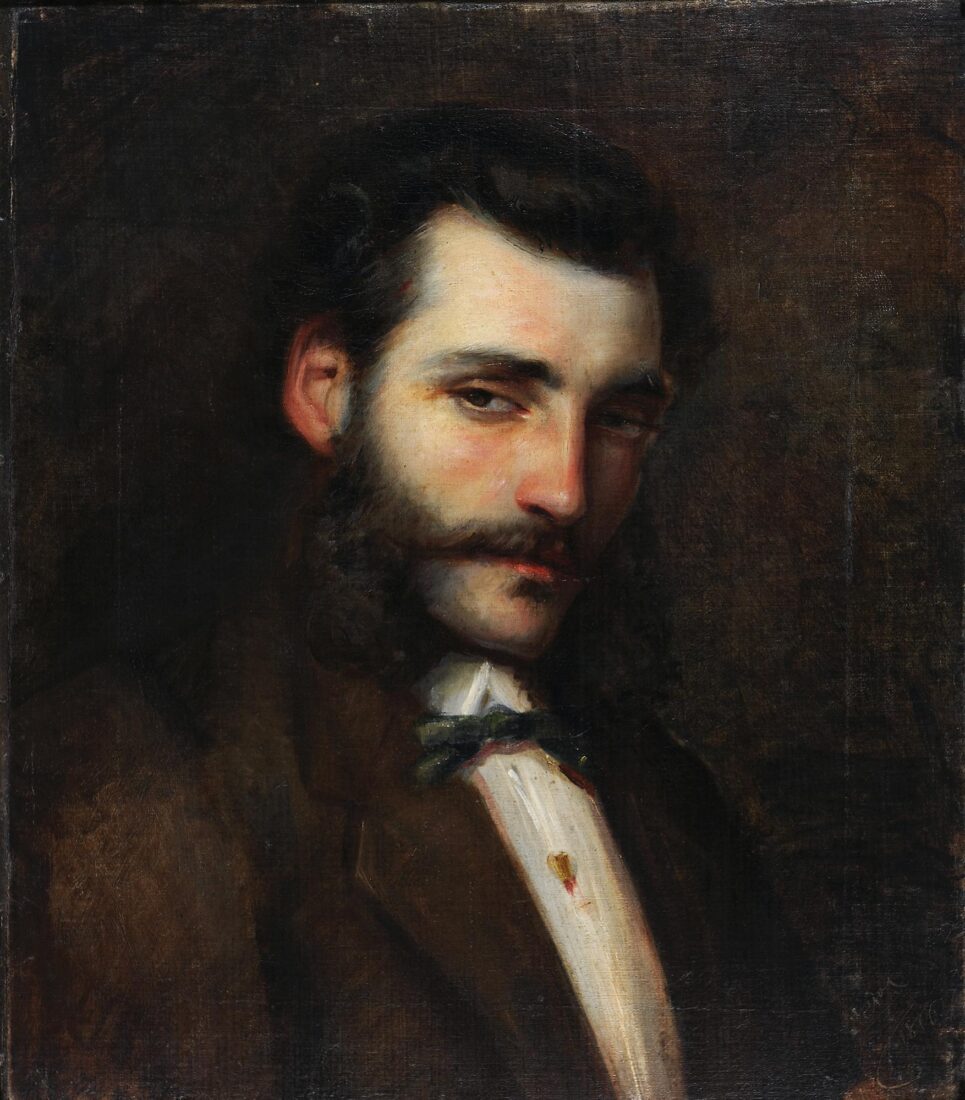

When this work was made part of the collection at the National Gallery, it was at first attributed to Jusepe de Ribera (1591-1652) who settled in Naples where he became acquainted with Caravaggio and fell under his influence. Professor Gerhard Ewald, however, attributed the work, in his book Johann Carl Loth (1632-1698), Amsterdam 1965, to the German painter Johann Carl Loth.

In the work at the National Gallery one sees, in all likelihood, a depiction of Plutarch’s version of how Archimedes died. This occurred during the conquest of the Syracusans by the Roman legions under Marcellus. “As fate would have it he was alone, intent on working out a problem by means of a diagram. And as both his mind and his eyes were absorbed with these speculations, he remained completely unaware of the Roman incursion, not even realizing the city had been taken. Suddenly, he found himself face to face with a soldier who commanded him to follow him to Marcellus. But Archimedes refused to budge until he had solved the problem to his satisfaction and demonstrated it. This infuriated the soldier who drew his sword and ran him through…” (translation of the relevant section on Marcellus of the Greek edition of “Plutarch’s Lives”, edit. Philologiki, vol. II, Athens, n.d., p. 212). In the painting, the soldier, holding his sword in one hand, has lifted it with a violent movement and is holding Archimedes by the throat; he appears quite unfazed, with an absorbed look and making an emphatic gesture which shows his determination to not go with him until he has solved the problem he is involved with.

The composition is faithful to all the elements characteristic of Loth’s works. The soldier and Archimedes create, with their bodies, the sphere and the account books, a compact group that occupies nearly the entire surface of the painting. The soldier, tall and well-built, is in almost complete shadow, standing behind Archimedes’ uplifted arm while the light falling on the primary plane in practically the center of the composition, creates contrasts between the light and dark planes, revealing the elderly body of Archimedes, still strong despite his great age, as well as his strong-willed personality. The dark brown colors in combination with the intense lighting serve to stress the dramatic character of the scene.