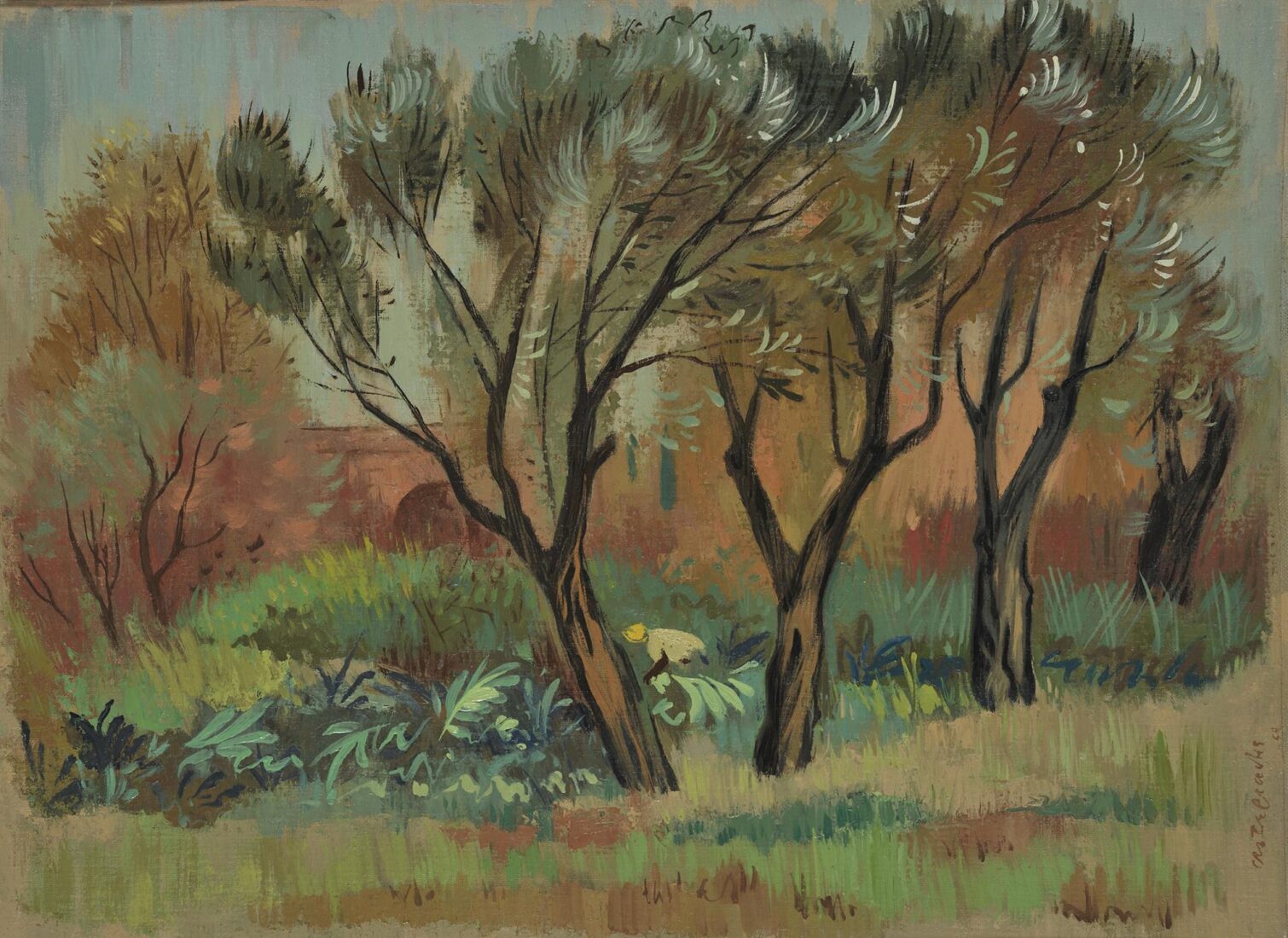

The nostalgia for a vanishing Athens, for an everyday familiarity rapidly disappearing in the anonymous mass of an impersonal megalopolis was an inexhaustible mine of inspiration for Uncle Spyros, as he was affectionately called by his many admirers. The folk roots of his painting, which combine tradition with modernism, establish him among the authentic representatives of the Thirties Generation, to which he also belonged chronologically.

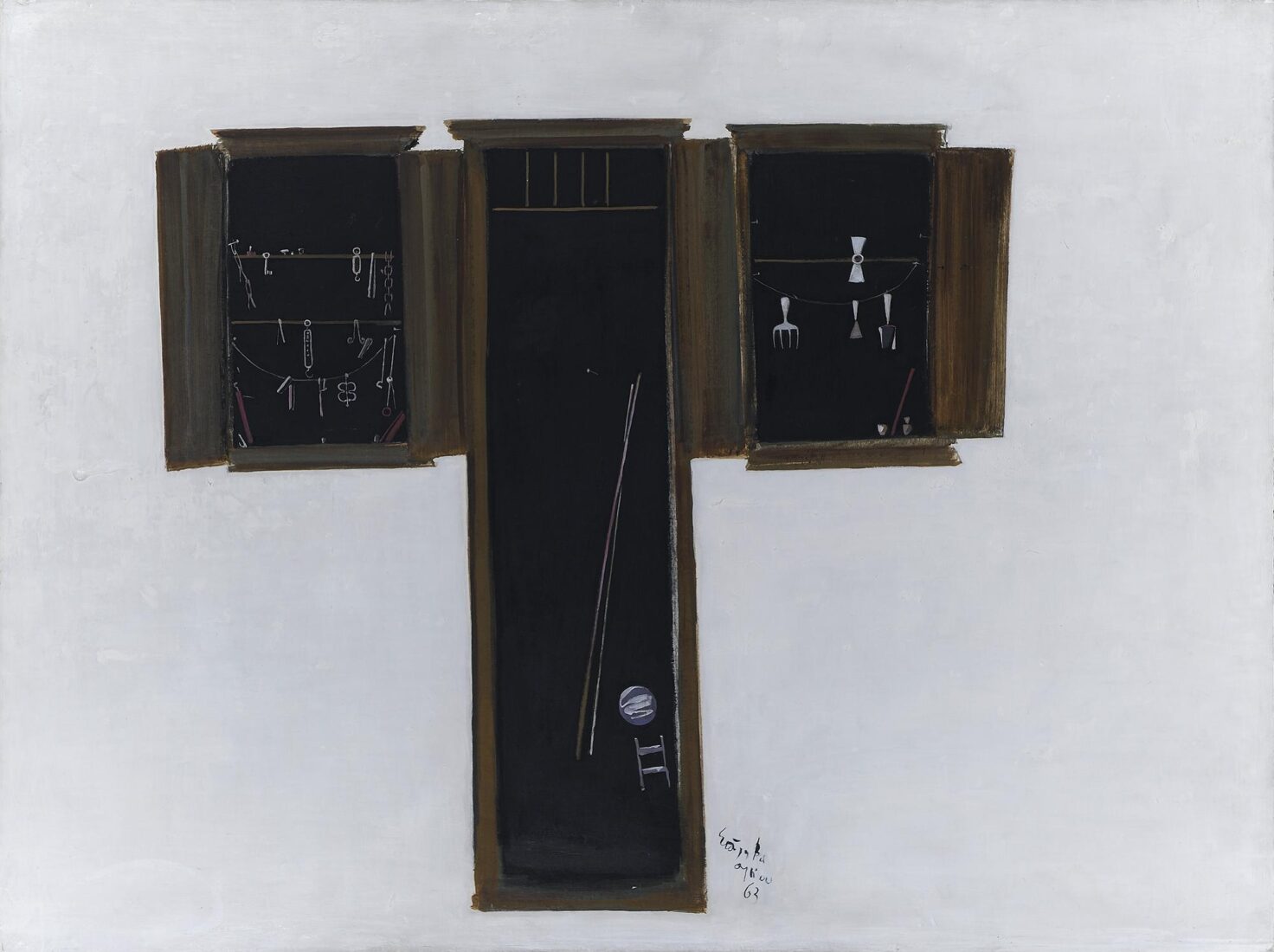

The Microcosm of Webster Street, which depicts a corner of his studio near the Acropolis, is an intimate representation of the painter’s world. An old mirror on a wall between two openings gives us the reflection of a half-finished painting of a solitary chair on the sand near the sea. This is one of the subjects Vassileiou enjoyed painting at his country home in Eretria.

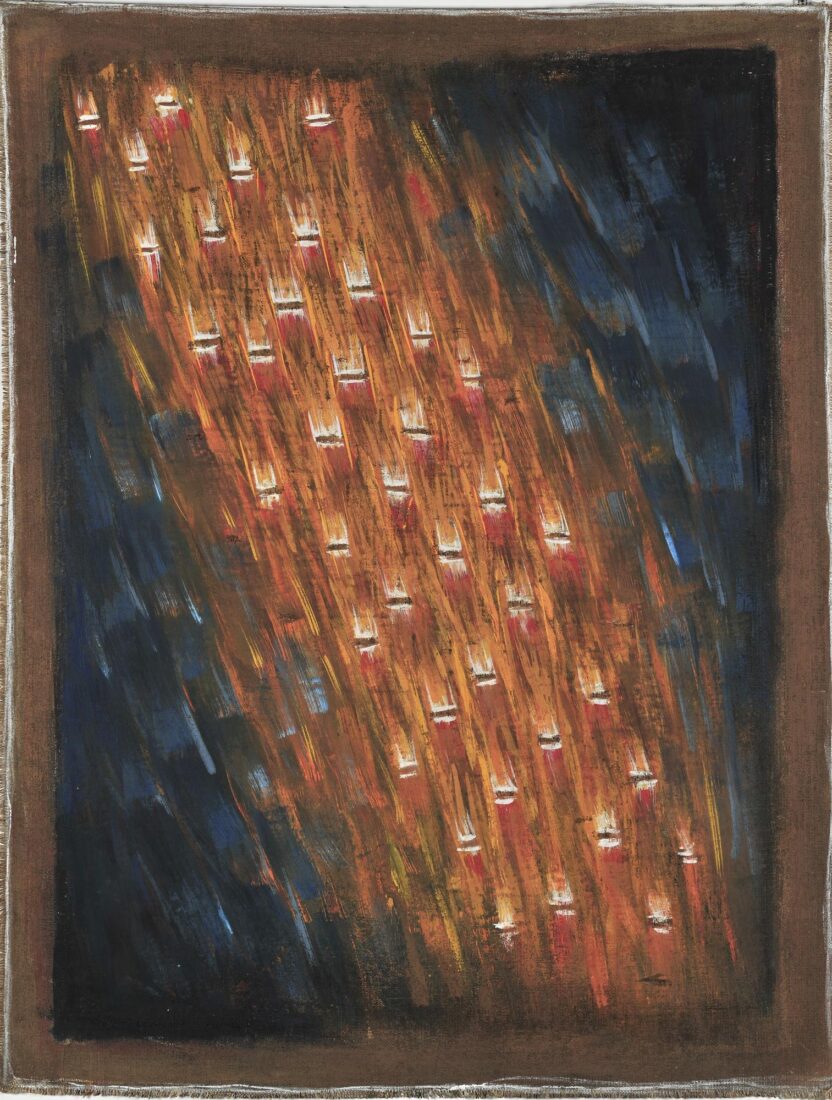

Another painting depicts the view of the Acropolis from his house, with all the newer buildings in the foreground. The juxtaposition of the ancient structures and the beautiful neoclassical ones with the tasteless, mass-produced new apartment buildings that had begun overwhelming Athens was one of Vassileiou’s favorite themes. The “actual” view of the Theater of Herodes Atticus and the Acropolis is revealed through two balcony doors to the left and right of the wall. The sky is covered with gold leaf. The multiple paintings captured within the painting, the reflections of paintings in the mirror, create an exciting picture of the type that long always enchanted painters, especially 16th century Mannerists. Vassileiou combines accurate drawing with the light, atmospheric colors that convey the ethereal quality of the Attic light. The golden ochre hues dialogue with complementary blues alongside the silence of the white wall.

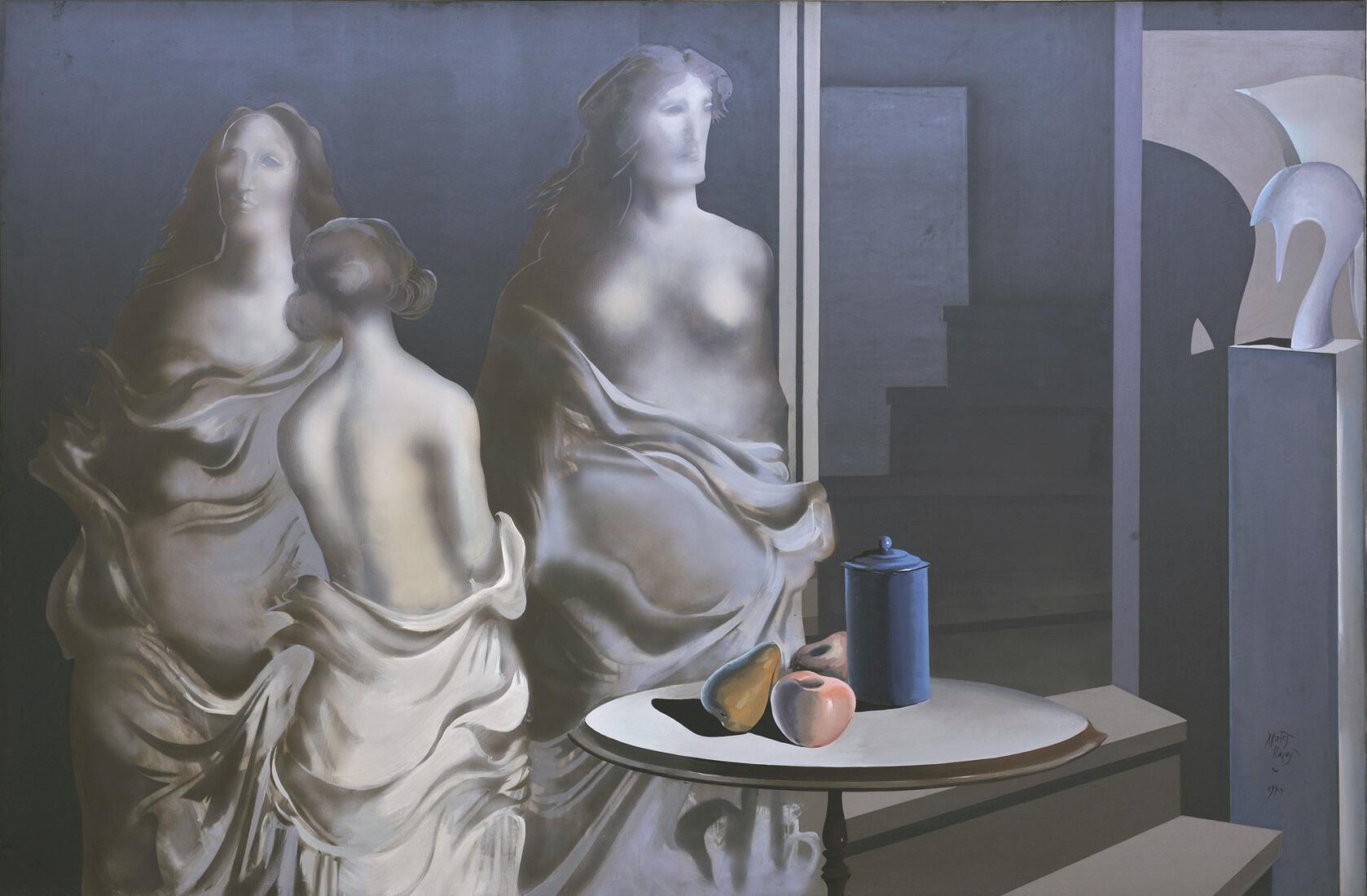

Christos Karas is a member of the dynamic Sixties generation that produced important painters and revitalized easel painting. His painting is anthropocentric. In the 1970s, impressed by Pop Art and American Hyperrealism, Karas invented a personal style in which human figures, flowers, fruits and objects are depicted in a manner influenced by graphic arts. In The Three Graces, the semi-nude female figures covered by billowing white mantles, atmospherically drawn with skillful chiaroscuro, stand out like spectral presences against a dark ground. In the foreground, a still life with fruit is depicted in the same manner. Through a half-open door we can make out an ancient-style white helmet placed on a tall rectangular plinth, which casts its dark shadow on the wall. With its spectral female figures and heteroclectic objects, the picture has an enigmatic and magical atmosphere. The composition, with its vertical elements that bisect the space according to the golden mean, is well-balanced. Except for the color in the still life, the painting is virtually monochromatic.

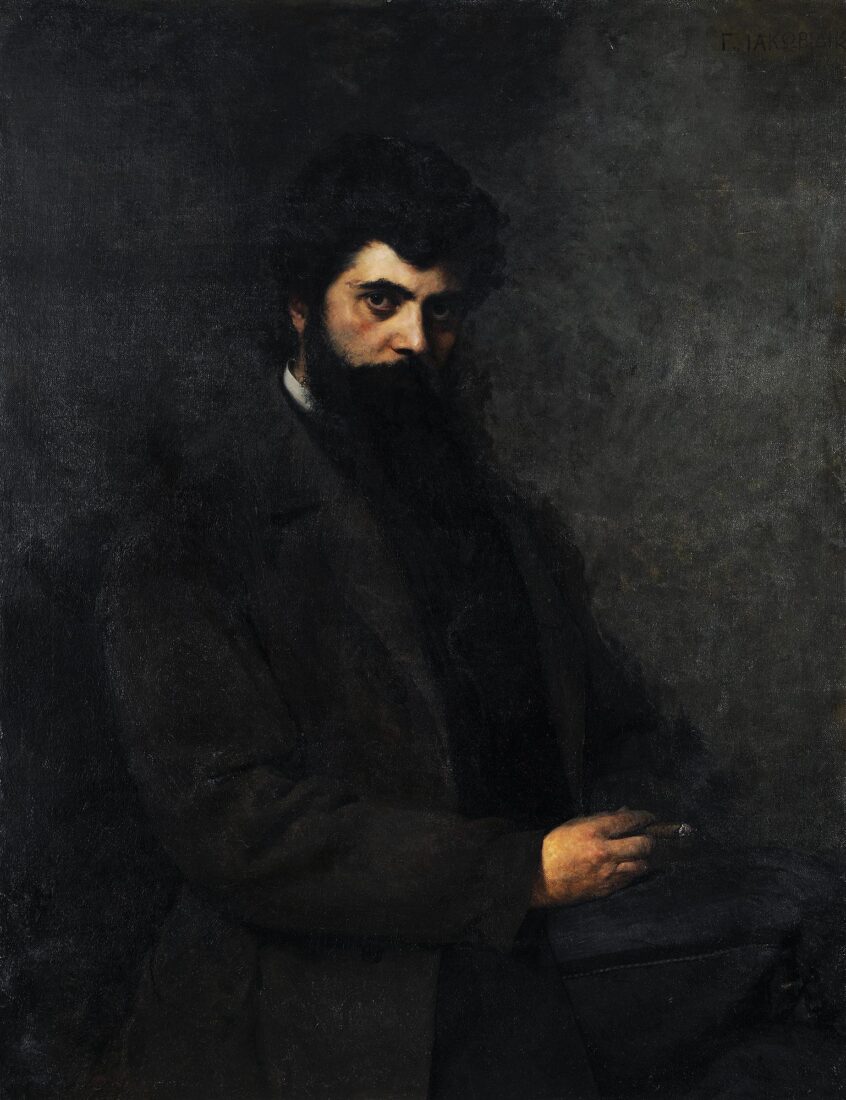

A Tyrolean painter working in Greece, Francesco Pige left us the most magnificent gallery of the Greek society in the early years of Independence. The frontal or three-quarter figures are portrayed looking towards the viewer, clad in traditional ethnic costumes and surrounded by elements either decorative or emblematic of their professions and social positions.

Kyriakoula Voulgari was the wife of Antonios Kriezis, who rose to political offices of the highest rank. She was member of Queen Amalia’s entourage. One of her jewels, carrying the royal emblems, reminds us of the fact.

Pige’s style is distinguished by his accurate depiction of faces and hands. An accuracy and clarity reminiscent of 15th century Flemish portraits, or those of the great French neoclassical painter Ingres. In capturing decorative details, though, such as embroidery, jewellery, in all their detail, Pige reminds us of naive, non-academic painters. He often forgets volume and perspective. Note how the flowers on Kyriakoula Voulgari’s scarf are rendered.

Another of Pige’s characteristic traits is that he does not use the brown colour, contrary to academic painters. To this he owes his clear and lucid colours.