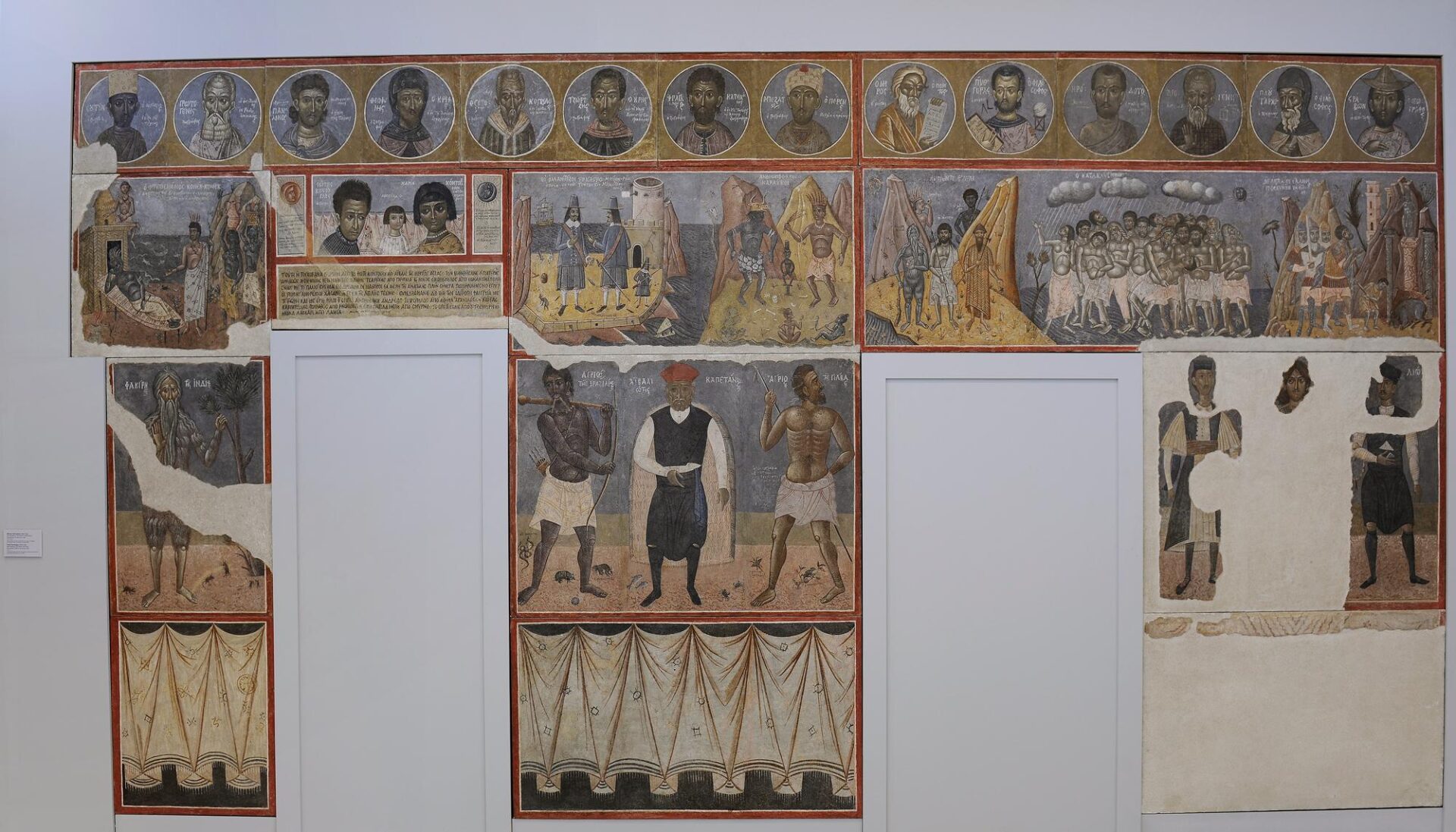

Lining the artist’s house, this monumental complex was detached from the wall thanks to a grant by brothers Vassilis and Nikos Goulandris in memory of their brother, Konstantinos. Kontoglou’s pupils Yannis Tsarouchis and Nikos Engonopoulos also contributed to the realisation of this imposing complex. The fact that the artist made this work for himself is important, as it means that there were no external specifications. He did what he liked, and this work indeed amounts to a confession, a personal testimony.

The wall is divided by red bands into architecturally organised sections of illustrated bands and paintings. There is a different scene in each room. The artist had studied this type of arrangement in post-Byzantine church decoration. Moreover, Kontoglou was a great church painter. At the bottom, he painted a folding white partition curtain, the common Byzantine church practice.

At the top section, within circular medals, he placed his pantheon, that is, every writer and painter he admired, from Homer, Pythagoras, Herodotus, Plutarch through the Byzantine iconographers Panselinos and Theofanis to Domenicos Theotocopoulos. They are all shown in the guise of ascetic Byzantine saints. There are 14 medals. The captions accompanying the figures are worth reading, as they reveal the literary and artistic models Kontoglou admired. On the lintel, always in the Byzantine manner, he depicted his family. Himself, his wife, Maria, and his only daughter, Despoula. On the left and right, he had painted the sun and the moon, according to the Byzantine iconographic practice. In the other images, Kontoglou imaginatively, almost with surrealist freedom, depicted the scenes which haunted his imagination, narrated in his wonderful tales. “”The Happy Konek-Konek,”” “”The Dutch”” seafarers, adjacent to the “”Man Eaters”” of the Caribbean; in the next scene, the ingenious artist depicted the “”Flood,”” inspired by the iconographic type of the SS Saranta Church. On the left of the door, the “”Indian fakir”” is depicted in the guise of an ascetic saint, while in the large painting between the two doors the artist placed side by side – in defiance of the laws of space and time – a “”Captain from Aivali”” in Asia Minor and a “”Savage from Java.”” Note the exotic animals and insects on the ground, accompanied by their name. Kontoglou was modern and surreal in his own way. The Byzantine technique, the codified drawing in the depiction of the body, the modelling in multiple layers — from the foundation through the skin tone to highlights — the Byzantine colours, ochre, sienna, brown, white, cinnabar for red, all unify these paradoxical alien creatures that co-inhabit his “”imaginary museum”” on the walls of his home. A fascinating world — at once familiar and outlandish. The lost paradise of the Orient of Fotis Kontoglou.

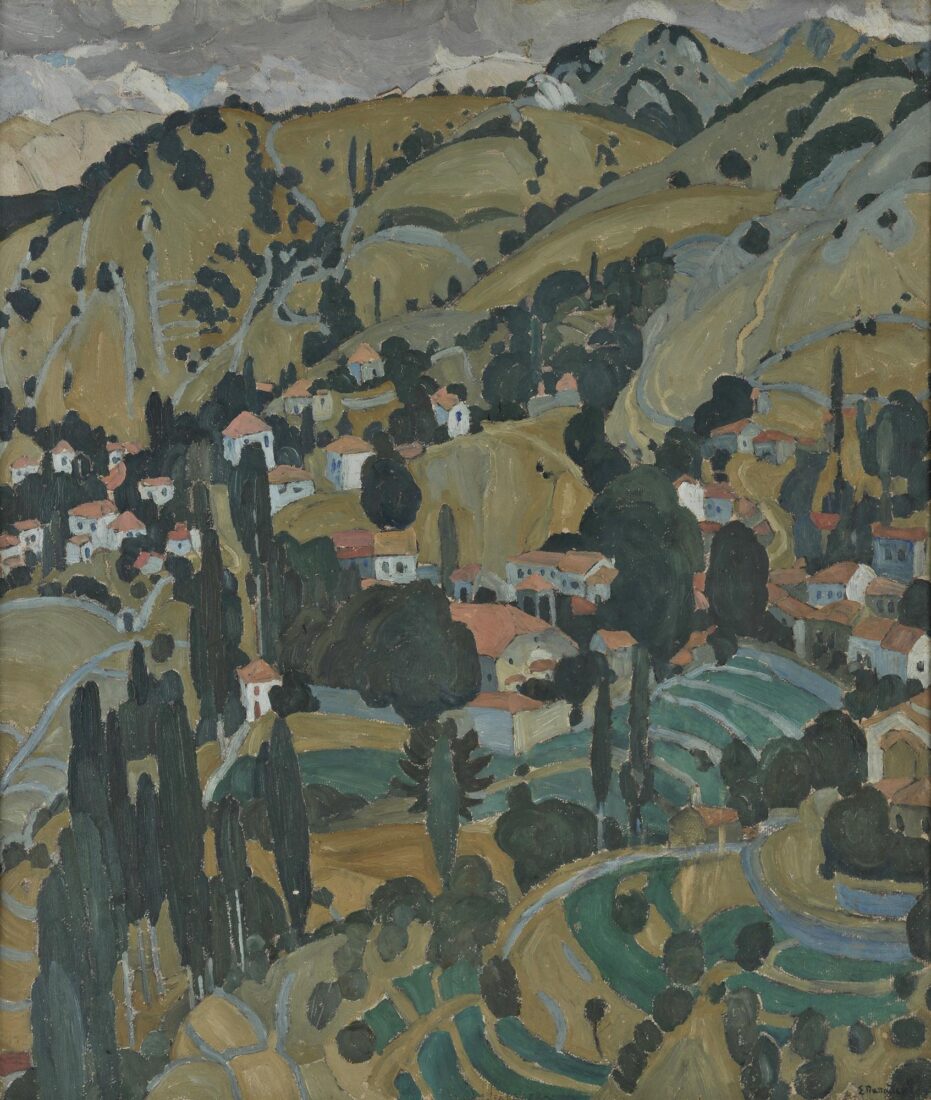

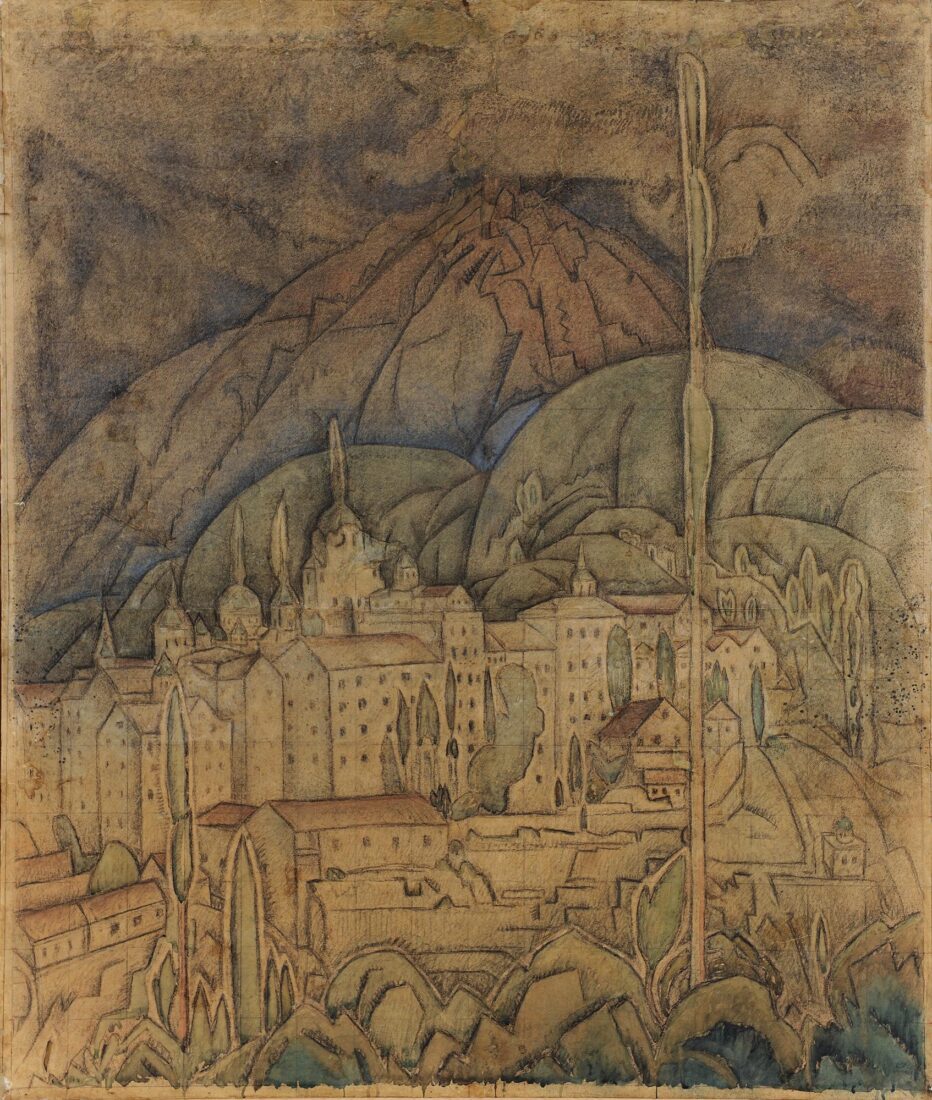

Fotis Kontoglou’s wall on display at the National Gallery introduces us to the room consigned to the generation of the Thirties. Before that, even in the Twenties, Greek painters employed vivid and natural colours — red, green, yellow, blue. Artists of the generation of the Thirties, even Parthenis, seem to have been influenced by Kontoglou’s Byzantine palette. This indicates how deeply Kontoglou influenced his contemporary painters, even those who were not members of his own circle. It must also be noted, though, that another influence, this time from Paris, also contributed to this shift towards more “”cerebral”” colours: This was the influence by Andre Derain (1880-1954), friend of the engraver and painter Dimitrios Galanis (1879-1966), who had also adopted the same dark palette, inspiring many Greek painters of the generation of the Thirties.

The “Boy with Suspenders” was painted in Mytilene but takes into consideration the lesson in Byzantine iconography that Papaloukas received during his visit to Mount Athos. Here, Papaloukas confirms the axiom that one must approach tradition through the precepts of modern art. The painter builds the boy’s portrait in clear shapes, painting each form in the appropriate colour in order to achieve an effect of volume. In this painting, Byzantine iconography and mosaic meet Cezanne’s teaching (1839-1906). Face and skin colours are part of the Byzantine palette: ochre, raw and burnt sienna. It is in a similar palette that Papaloukas paints the boy’s exquisite striped shirt. The striped cloth on the table in the background is in cooler tones. The “Boy with Suspenders” reveals a great artist of assured technique, luscious colour and great sensitivity. The boy, looking at us with a puzzled look, his grey eyes and his red mouth half-open, is a psychological portrait of a village boy about to enter the trial of adolescence.