Yannoulis Chalepas was an extraordinarily gifted artist. Yet, his life and career as an artist were branded by the outbreak of a mental illness, which led to his institutionalisation at the mental hospital on Corfu and to a 40-year hiatus in his work. The first symptoms of a deviating behaviour became manifest in 1878, at which time the first period of his creative production came to an end.

During that period, Chalepas was thematically inspired by the Greek Antiquity and mythology, in accordance with the neoclassical spirit which prevailed in 19th-century Greek sculpture. “Satyr Playing with Eros” is a characteristic work in this respect. It is, moreover, the first of 12 related works made by the sculptor.

In this first variation, Chalepas created an open, multi-axial composition of vivid motion, reminiscent of Hellenistic art, able to be viewed from multiple points, characteristic of his work in general. Neoclassical elements can be identified in the nudity of the figures, the rendering of the eyes without pupils and irises, as well as in the soft, almost impeccably polished surface of the marble, which enables the light to glide smoothly. The tender body of Eros is projected upon the shadow of the Satyr’s breast. Contrary to many images depicting satyrs as repugnant old men, Chalepas chiselled the figure of an adolescent, whose dual nature is only evoked by a short tail at the base of the spine, the pointed ears and the two small horns, which can barely be seen high on the forehead.

The first effect created by the work is of a joyful scene, full of innocence and insouciance. Yet, upon a closer look, it becomes apparent that the Satyr’s grin is a mocking one, and his expression is cruel and disparaging. It is in vain that little Eros is trying to reach for the grapes.

What is evoked here for the first time is the sculptor’s relationship with his father. Chalepas’s father had been opposed to his son’s artistic vocation right from the start. From 1918 until 1936, Chalepas made 11 more works on the theme of Satyr and Eros in clay or plaster. These works reflect Chalepas’s gradual liberation from the tyrannical figure of the father.

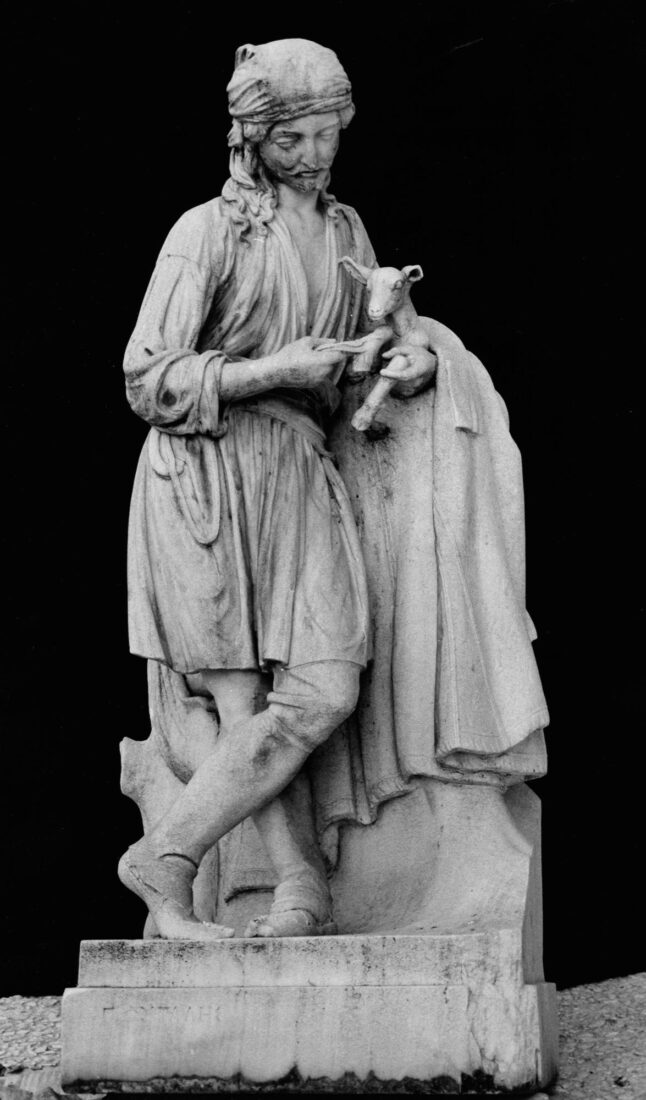

A work that came into the National Gallery collection in 1949, with the bequest of Nicholaos I. Iliopoulos, “Shepherd with Baby Goat” is a characteristic piece by Georgios Fytalis, dating from his period of study at the Athens School of Fine Arts. The work had been submitted at the Kontostavleios competition, in 1856. Both the Fytalis brothers entered the competition, in which their works received an equal number of votes and they shared the first prize. Only Georgios’s work was cast in marble, though.

“Shepherd with Baby Goat” combines the typology of ancient Greek sculpture with neoclassical idealisation, and the meticulous rendition of individual elements with the realistic qualities of an early, for Modern Greek sculpture, genre approach.

Yannoulis Chalepas was a uniquely gifted artist. But his life and artistic development were marked by the manifestation of mental illness that led to confinement in a psychiatric hospital on the island of Corfu and a forty-year hiatus in his artistic production. The first symptoms of aberrant behavior presented in 1878, the same year that he completed his first body of work, referred to by historians as the “first period.”

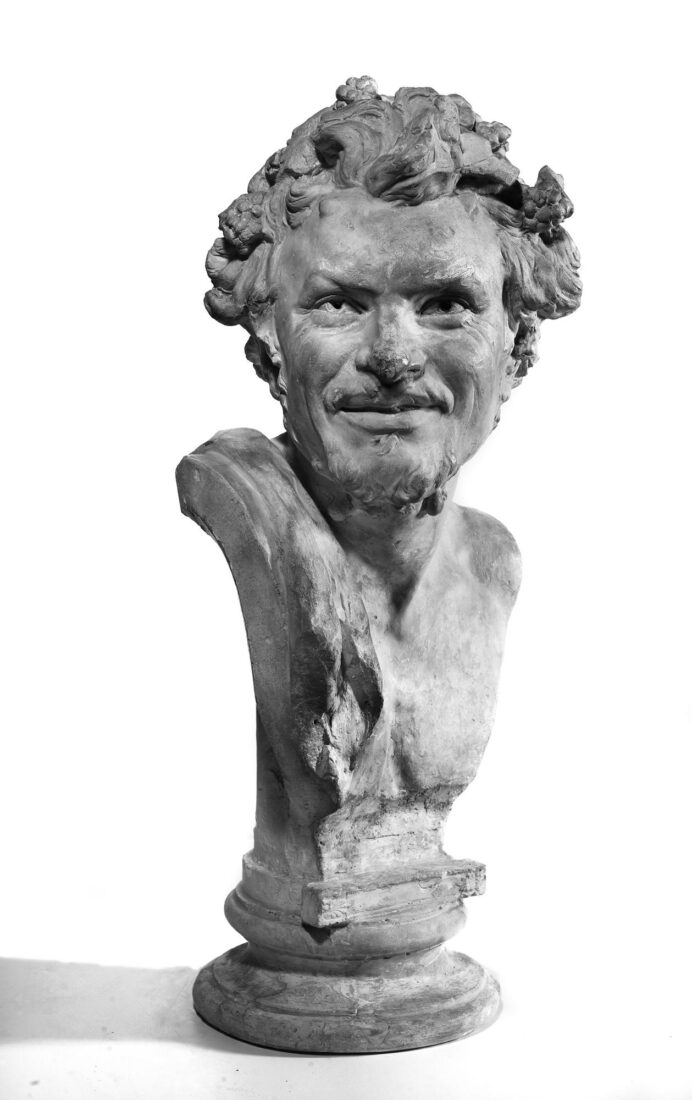

“Satyr’s Head” is among the last works of Yannoulis Chalepas’ first creative period. A realistic, highly modeled figure, it is a virtually psychographic, personal portrait of a mature man. The vivid, penetrating gaze and enigmatic smile establish the figure’s personality. The smile appears at once sarcastic or demonic and melancholy, depending on the angle from which it is regarded. In fact, this piece caused Chalepas such emotional distress that he tried to destroy it by scratching and throwing clay at it.

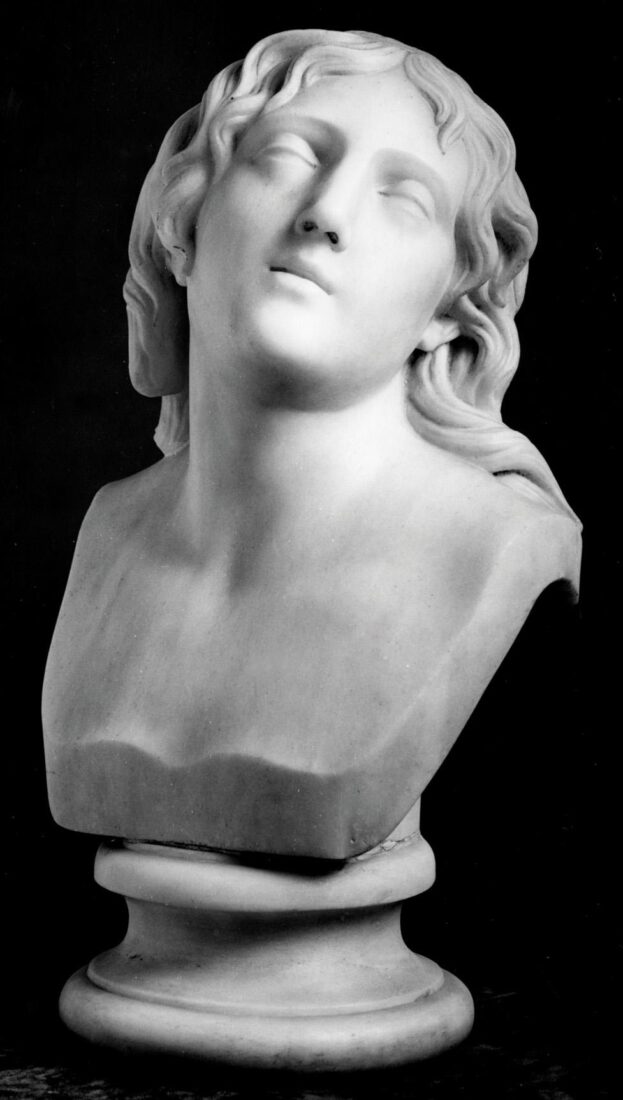

Ioannis Kossos was one of the first modern Greek sculptors to graduate from the Athens School of Arts and fashioned his style in the neoclassicist spirit that the German sculptor Christian Siegel brought to Greece. His subject matter included busts, statues, funerary monuments and allegorical compositions, or inspired by antiquity. To this last category belong the two youthful figures that symbolize Eros and Psyche, carrying on the tradition that started in antiquity and reappeared in European neoclassicist sculpture.

For the rendering of this subject, Kossos elected to carve two separate heads which could stand on their own as autonomous works, while at the same time they had a direct connection to each other and where the one supplemented the other. “Eros” is presented as being somewhere between an adolescent and a man, with an expression proud and self-confident, his lips half-open and his head turned to the left, toward “Psyche”. “Psyche” is presented in the form of a young woman, her head pulled back voluptuously, surrendering to the charms of Eros.

The rendering of these two figures is done according to the neoclassicist tradition, with the consequent affectation in pose and expression, the nudity of the bodies and the soft and smooth framing of the surfaces, without fluctuations, and emphasis on details.

Ioannis Kossos was one of the first modern Greek sculptors to graduate from the Athens School of Arts and fashioned his style in the neoclassicist spirit that the German sculptor Christian Siegel brought to Greece. His subject matter included busts, statues, funerary monuments and allegorical compositions, or inspired by antiquity. To this last category belong the two youthful figures that symbolize Eros and Psyche, carrying on the tradition that started in antiquity and reappeared in European neoclassicist sculpture.

For the rendering of this subject, Kossos elected to carve two separate heads which could stand on their own as autonomous works, while at the same time they had a direct connection to each other and where the one supplemented the other. “Eros” is presented as being somewhere between an adolescent and a man, with an expression proud and self-confident, his lips half-open and his head turned to the left, toward “Psyche”. “Psyche” is presented in the form of a young woman, her head pulled back voluptuously, surrendering to the charms of Eros.

The rendering of these two figures is done according to the neoclassicist tradition, with the consequent affectation in pose and expression, the nudity of the bodies and the soft and smooth framing of the surfaces, without fluctuations, and emphasis on details.

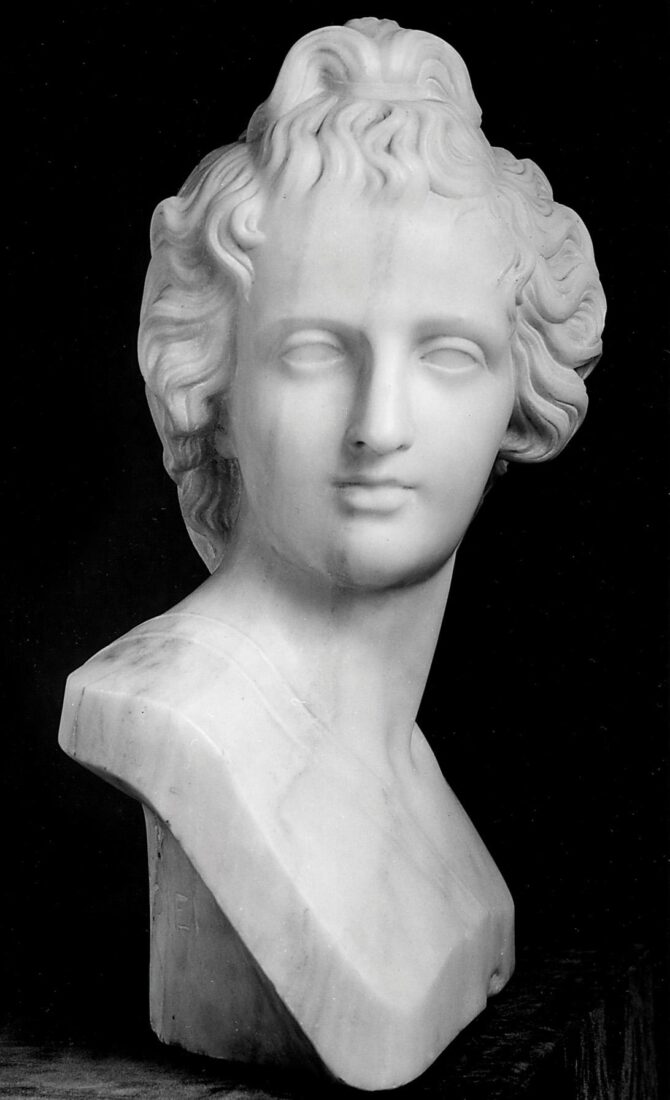

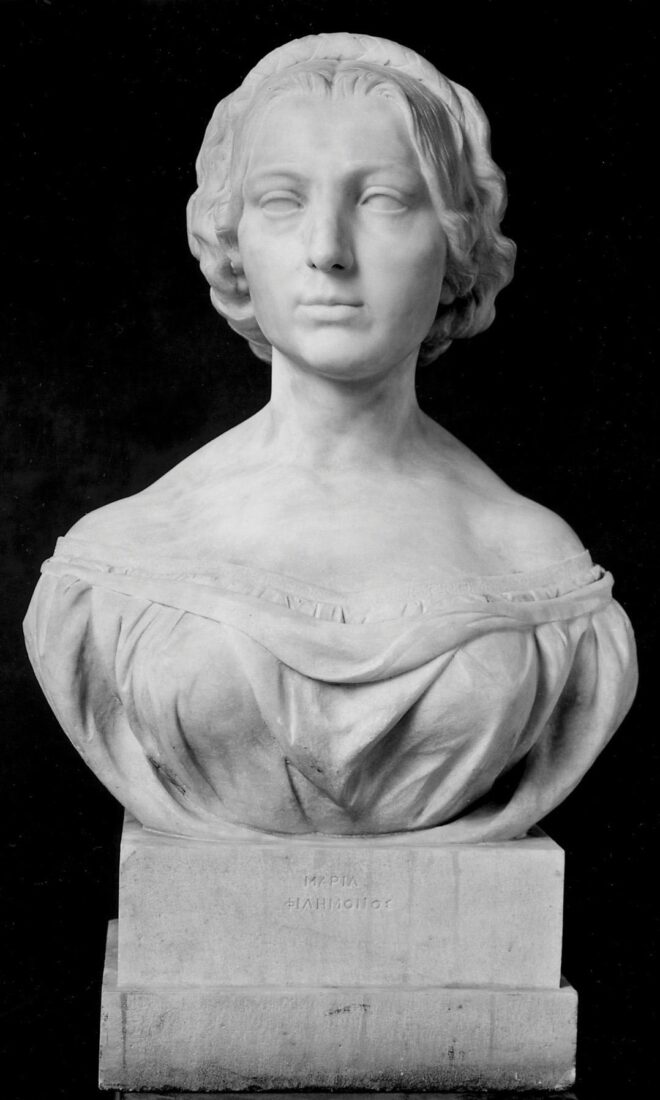

“Maria Filemonos” is a typical example of a bust rendered with particular care where female grace and elegance is stressed. In keeping with neoclassicist models, the young woman is rendered with delicate and idealized characteristics and a fixed look, intensified by the rendering of the eyes without pupil or iris, but the soft framing of the face, the slight turning of the head left and the faint contraction of the lips meant the formal and lifeless rendering these works are usually prone to, was thus avoided. The hair, carefully done, is parted down the middle and decorated with a delicate diadem, while in back it ends in a loose braid. The shoulders are left bare, revealing the upper chest and the soft rise and fall of the surface, while the bosom is discreetly noted under the drapery of the dress.

The work was executed jointly by Georgios and Lazaros Fytalis. In 1859 it was presented in plaster at the Olympia Exhibition in Athens and in 1862 in marble at the International Exhibition of London.

Leonidas Drossis belonged to the first generation of modern Greek sculptors who studied at the Athens School of Arts and were shaped in the spirit of neoclassicism that was brought to Greece by the German sculptor Christian Siegel. Broadening his education at the Munich Academy under Max Widnmann and with trips to Paris, London, Dresden, Vienna and Rome, where he opened a workshop, he would prove to be the most important representative of Greek neoclassicism.

Penelope emanates from Drossis’ cycle of mythological themes. The final model was done in Rome, in all likelihood in 1867, since that very same year it was presented at the International Exhibition of Paris where it won the gold medal. In 1870 it was exhibited at the Olympia exhibition, along with the first small model from 1864, and won the gold medal there as well. King George I allocated thirty thousand drachmas to transfer it to marble and after it was completed it was placed on the golden stairway of the Royal Palace.

Seated on an elaborately ornamented throne, Penelope is seen holding the ball of thread and the spindle, her crossed legs stretched out before her, resting on a decorated stool. Her pose is influenced by the ancient Greek Pheidian model of “Aphrodite”, a tradition that was carried on in “Agrippina” from the 4th century AD in the Capitoline Museum in Rome and the mother of Napoleon, “Letizia Ramolino Bonaparte” (1804-1807) by Antonio Canova.

Both the pose of the body and the head, which is bent slightly to the left, and the melancholic expression on the face reveal the fatigue and the sense of abandonment in addition to the fortitude of this woman who had to wait for her husband to return for so many years. Thus, the work is connected with the romantic aspect of the European neoclassicism, which emphasizes the feeling against the logic and portrays personal psychological states. Furthermore, despite the neoclassicistic characteristics, the depiction of these human emotions differentiates “Penelope” from the ancient models.

“The Spirit of Copernicus” is a unique example of an early and exceptionally daring composition for the Greek public. Vroutos made the plaster model in 1873, while he was in Rome, and in 1875 exhibited it at the Olympia exhibition, where he won the “silver medal second class”. In 1878 he presented it at the International Exhibition of Paris, while in 1881 at the exhibition held at the Vassilios Melas mansion for the benefit of the Red Cross.

The spirit of the leading astronomer, who reversed the dominant theory by claiming that the earth and the planets move around the sun, and not vice versa, is depicted in an equally subversive composition: an inverted winged young figure leans against the terrestrial globe with its right hand, while spinning it at the same time. He points towards the sun with his left hand. The inverted figure with its legs in the air was already known from the Hellenistic composition of the “Boy with the Dolphin” (Roman copy at the National Museum of Naples), from which Vroutos borrowed the stance of the boy, as well as the embracing of the head of the dolphin. A similar stance, originating from a Roman composition, was repeated in the work by Canova, “Hercules and Lichas” (1795-1815, Galleria Nazionale d’ Arte Moderna, Rome). The winged figure, moreover, which symbolizes the spirit of an eminent figure and supports itself on a globe, was already known from Descartes’ cenotaph at the church of Adolf Fredrik in Stockholm, by the Swedish sculptor Johan Tobias Sergel (1740-1814). In any case, for the Greek public, this composition was exceptionally daring and the endeavor was not carried on any further.