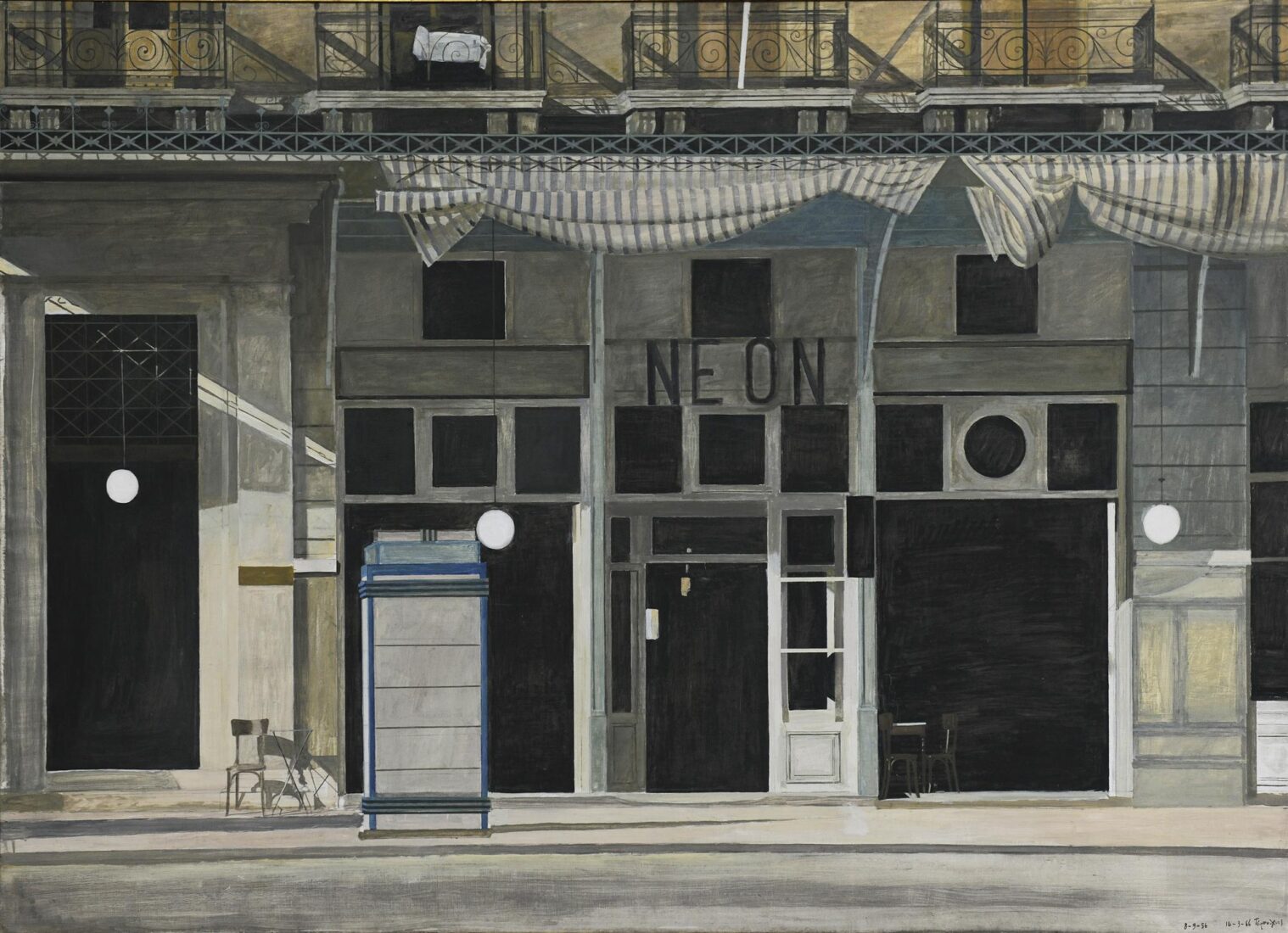

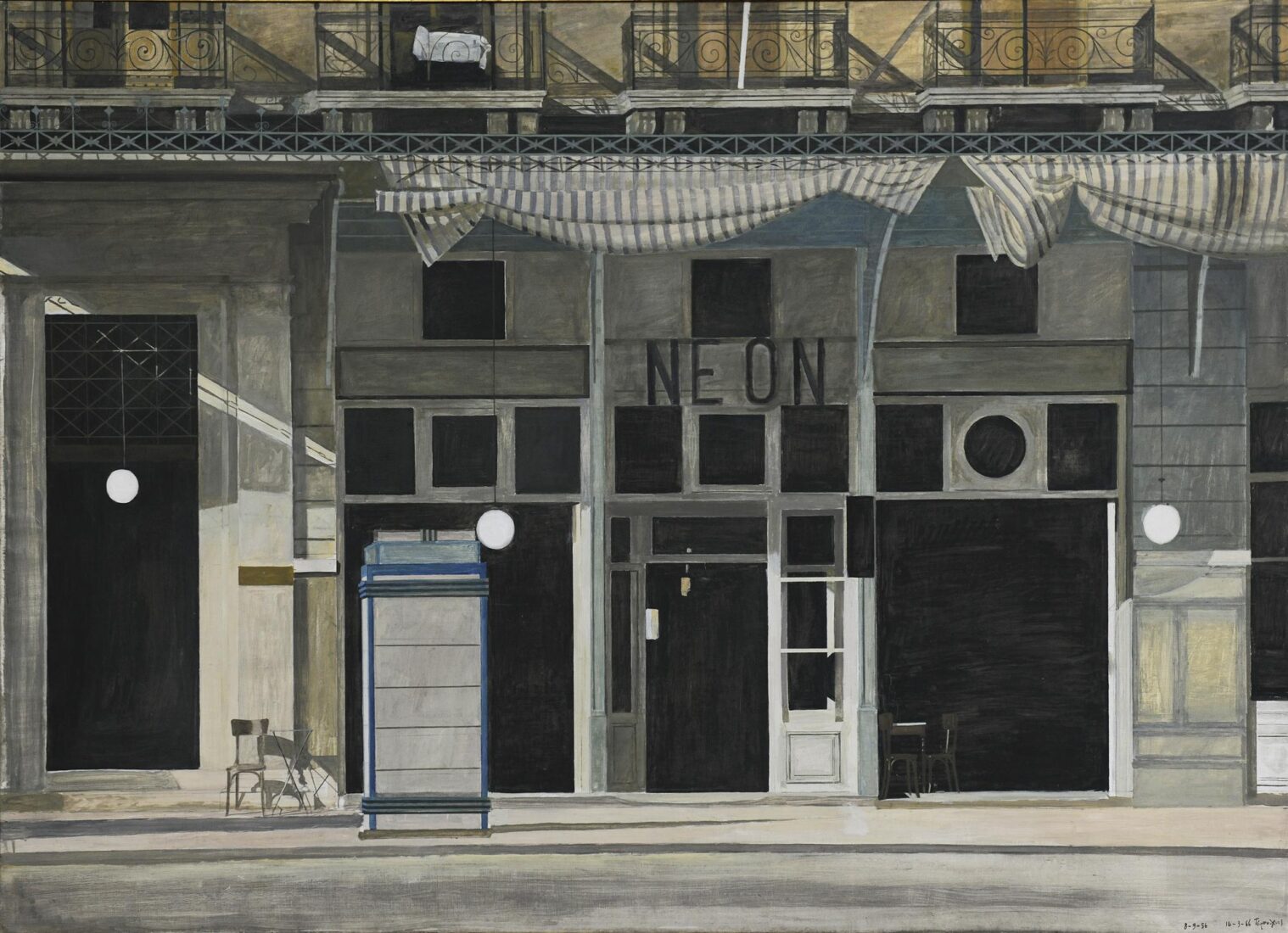

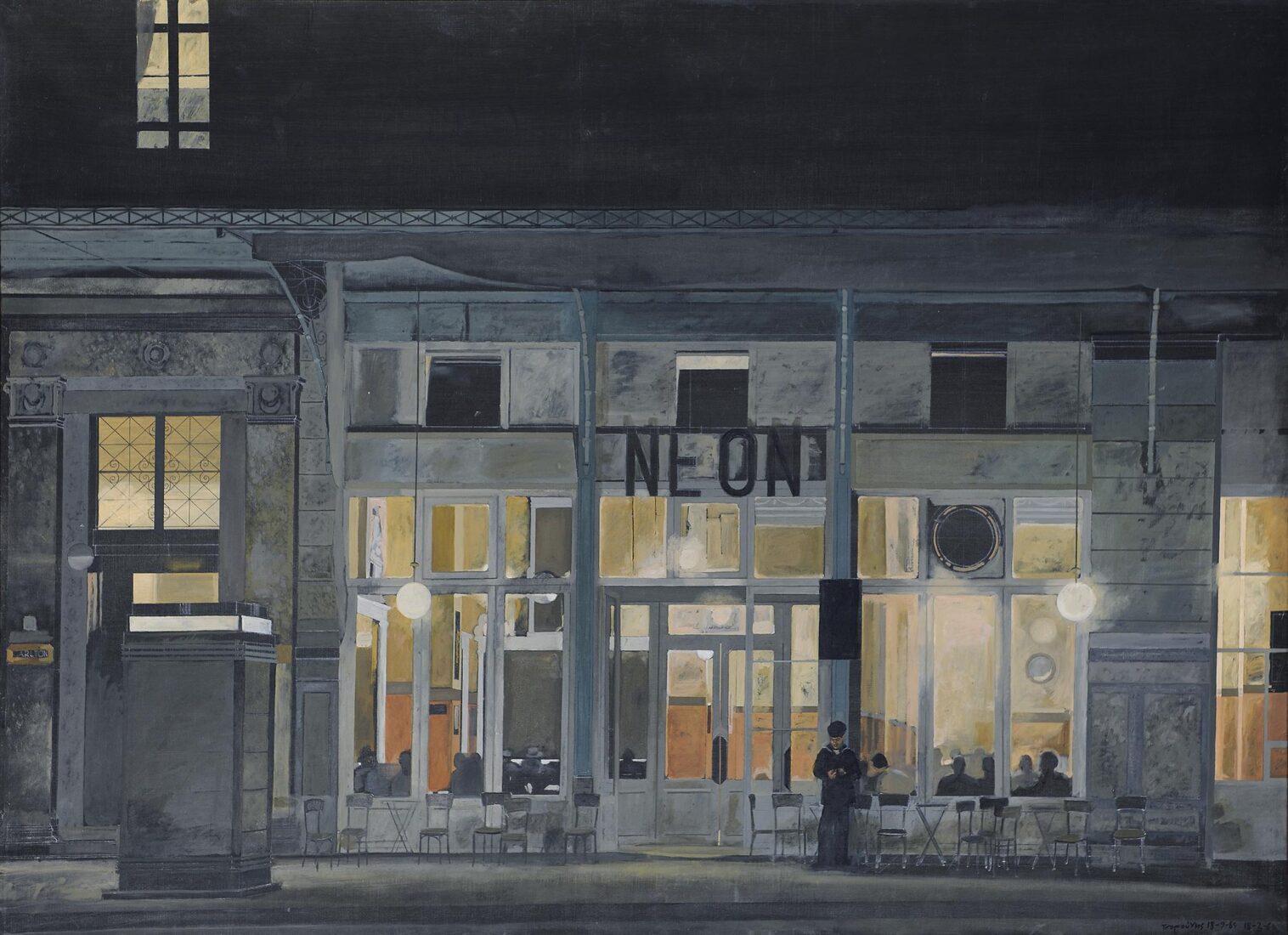

The subject of this diptych by Yannis Tsarouchis is the Neon Cafe as it was in 1956-1966 and still exists in Omonia Square. A daytime version preceded the nighttime view, which is interpreted here. In both compositions Tsarouchis depicts his subject, the facade of the cafe, frontally, eschewing perspectival illusion. The coffeehouse in Omonia Square was an emblematic theme for Tsarouchis, being the place frequented by the painter’s heroes – sailors and working-class youths. The coffeehouse was the stage upon which unfolded the everyday events that charmed this characteristic representative of the Thirties Generation. There are, however, other elements that Tsarouchis wished to call attention to in this theme: the architectural design of the cafe’s facade with its play of rectangular openings, doors and windows creates a grid pattern evocative of Mondrian, the innovator of geometric abstraction. Tsarouchis created an exciting play between abstraction and realism, between modernism and tradition.

The nighttime coffeehouse has the additional factor of artificial lighting, the white, yellow and orange lights that animate the painting’s generally black and grey palette. Here, the cafe’s patrons, a handful of small dark silhouettes, have become a secondary theme. In the daytime version they are absent entirely. Painted with classical austerity, Tsarouchis’ two cafes are his most abstract, modern and suggestive works.

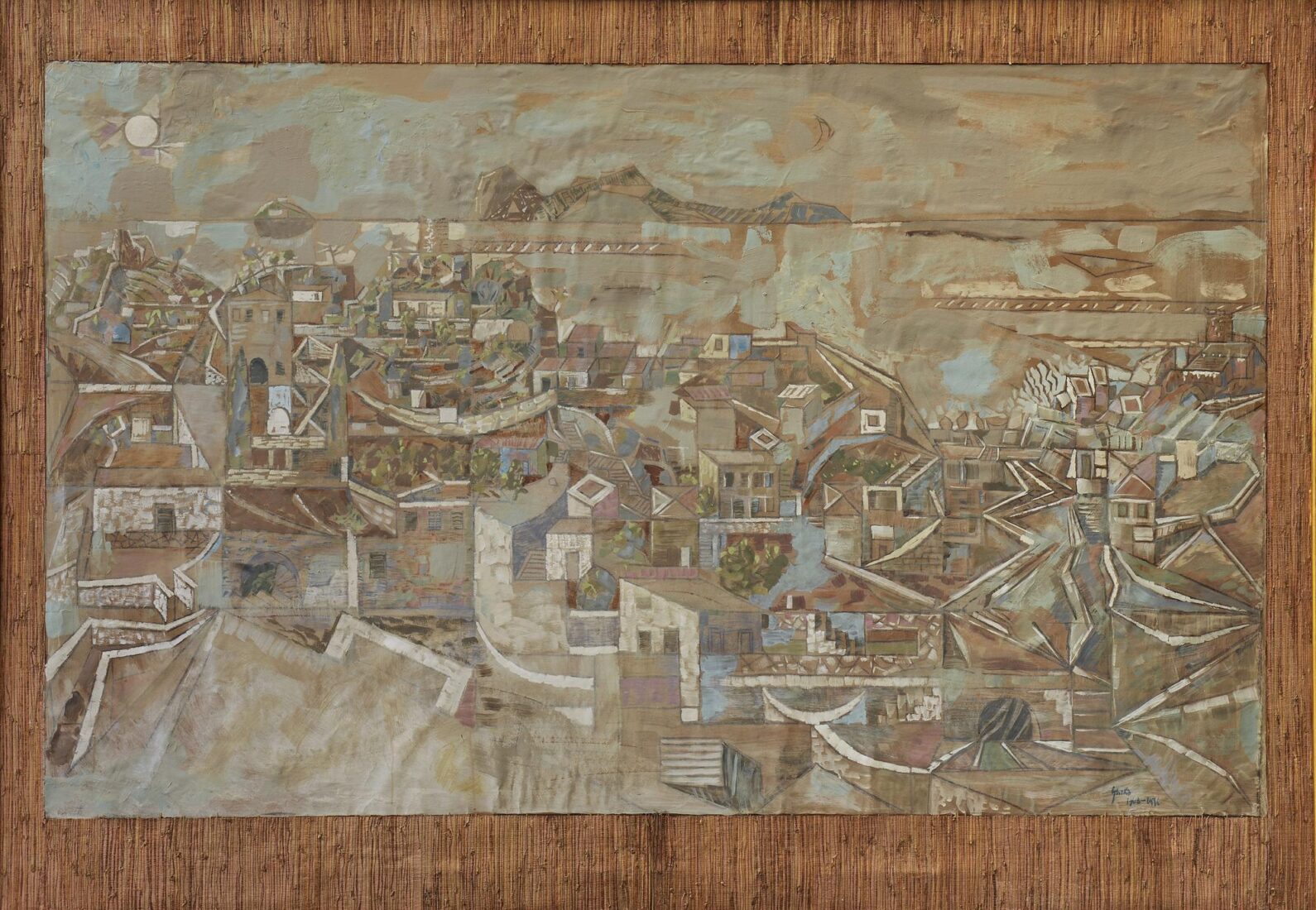

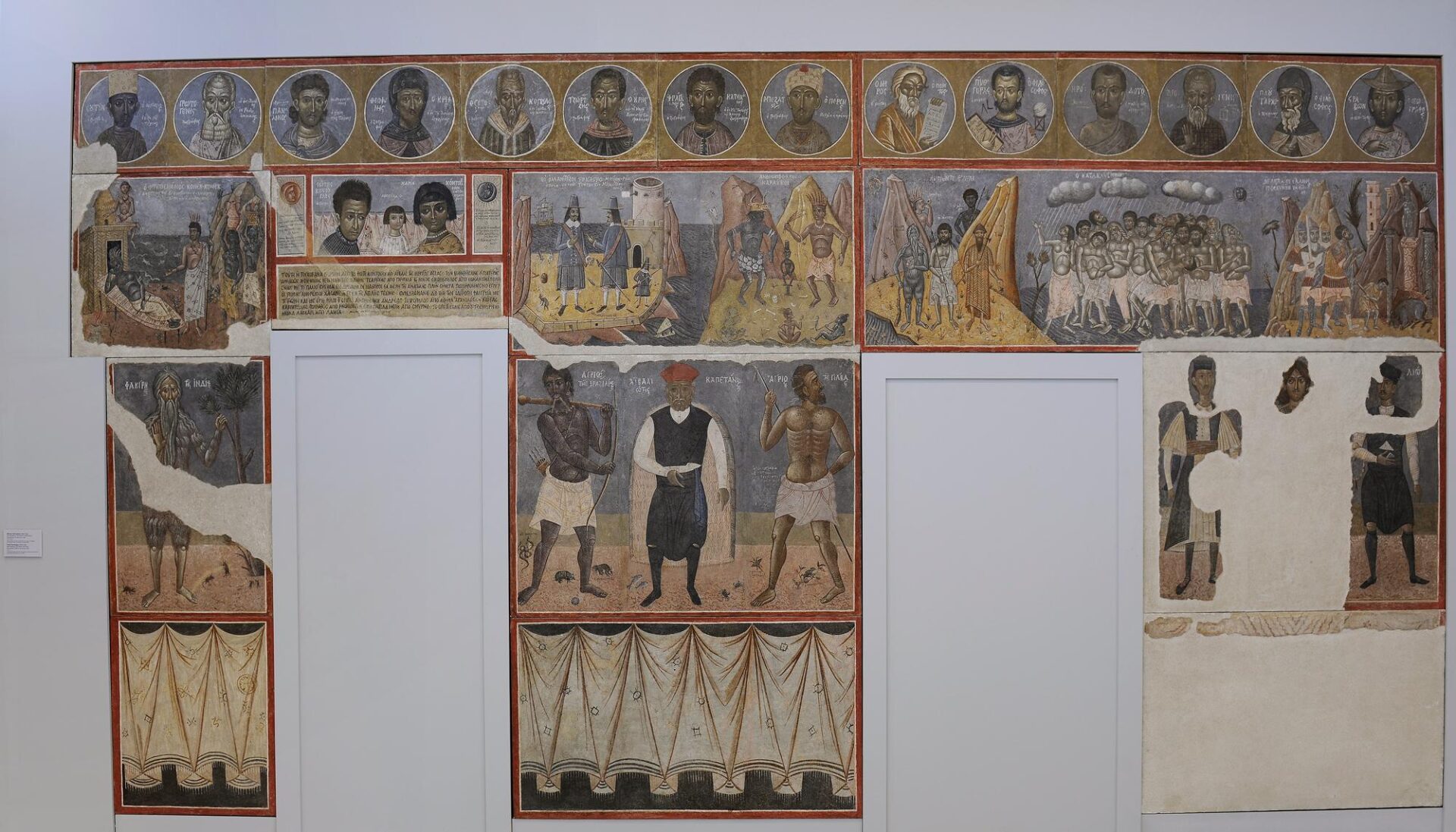

Lining the artist’s house, this monumental complex was detached from the wall thanks to a grant by brothers Vassilis and Nikos Goulandris in memory of their brother, Konstantinos. Kontoglou’s pupils Yannis Tsarouchis and Nikos Engonopoulos also contributed to the realisation of this imposing complex. The fact that the artist made this work for himself is important, as it means that there were no external specifications. He did what he liked, and this work indeed amounts to a confession, a personal testimony.

The wall is divided by red bands into architecturally organised sections of illustrated bands and paintings. There is a different scene in each room. The artist had studied this type of arrangement in post-Byzantine church decoration. Moreover, Kontoglou was a great church painter. At the bottom, he painted a folding white partition curtain, the common Byzantine church practice.

At the top section, within circular medals, he placed his pantheon, that is, every writer and painter he admired, from Homer, Pythagoras, Herodotus, Plutarch through the Byzantine iconographers Panselinos and Theofanis to Domenicos Theotocopoulos. They are all shown in the guise of ascetic Byzantine saints. There are 14 medals. The captions accompanying the figures are worth reading, as they reveal the literary and artistic models Kontoglou admired. On the lintel, always in the Byzantine manner, he depicted his family. Himself, his wife, Maria, and his only daughter, Despoula. On the left and right, he had painted the sun and the moon, according to the Byzantine iconographic practice. In the other images, Kontoglou imaginatively, almost with surrealist freedom, depicted the scenes which haunted his imagination, narrated in his wonderful tales. “”The Happy Konek-Konek,”” “”The Dutch”” seafarers, adjacent to the “”Man Eaters”” of the Caribbean; in the next scene, the ingenious artist depicted the “”Flood,”” inspired by the iconographic type of the SS Saranta Church. On the left of the door, the “”Indian fakir”” is depicted in the guise of an ascetic saint, while in the large painting between the two doors the artist placed side by side – in defiance of the laws of space and time – a “”Captain from Aivali”” in Asia Minor and a “”Savage from Java.”” Note the exotic animals and insects on the ground, accompanied by their name. Kontoglou was modern and surreal in his own way. The Byzantine technique, the codified drawing in the depiction of the body, the modelling in multiple layers — from the foundation through the skin tone to highlights — the Byzantine colours, ochre, sienna, brown, white, cinnabar for red, all unify these paradoxical alien creatures that co-inhabit his “”imaginary museum”” on the walls of his home. A fascinating world — at once familiar and outlandish. The lost paradise of the Orient of Fotis Kontoglou.

Fotis Kontoglou’s wall on display at the National Gallery introduces us to the room consigned to the generation of the Thirties. Before that, even in the Twenties, Greek painters employed vivid and natural colours — red, green, yellow, blue. Artists of the generation of the Thirties, even Parthenis, seem to have been influenced by Kontoglou’s Byzantine palette. This indicates how deeply Kontoglou influenced his contemporary painters, even those who were not members of his own circle. It must also be noted, though, that another influence, this time from Paris, also contributed to this shift towards more “”cerebral”” colours: This was the influence by Andre Derain (1880-1954), friend of the engraver and painter Dimitrios Galanis (1879-1966), who had also adopted the same dark palette, inspiring many Greek painters of the generation of the Thirties.

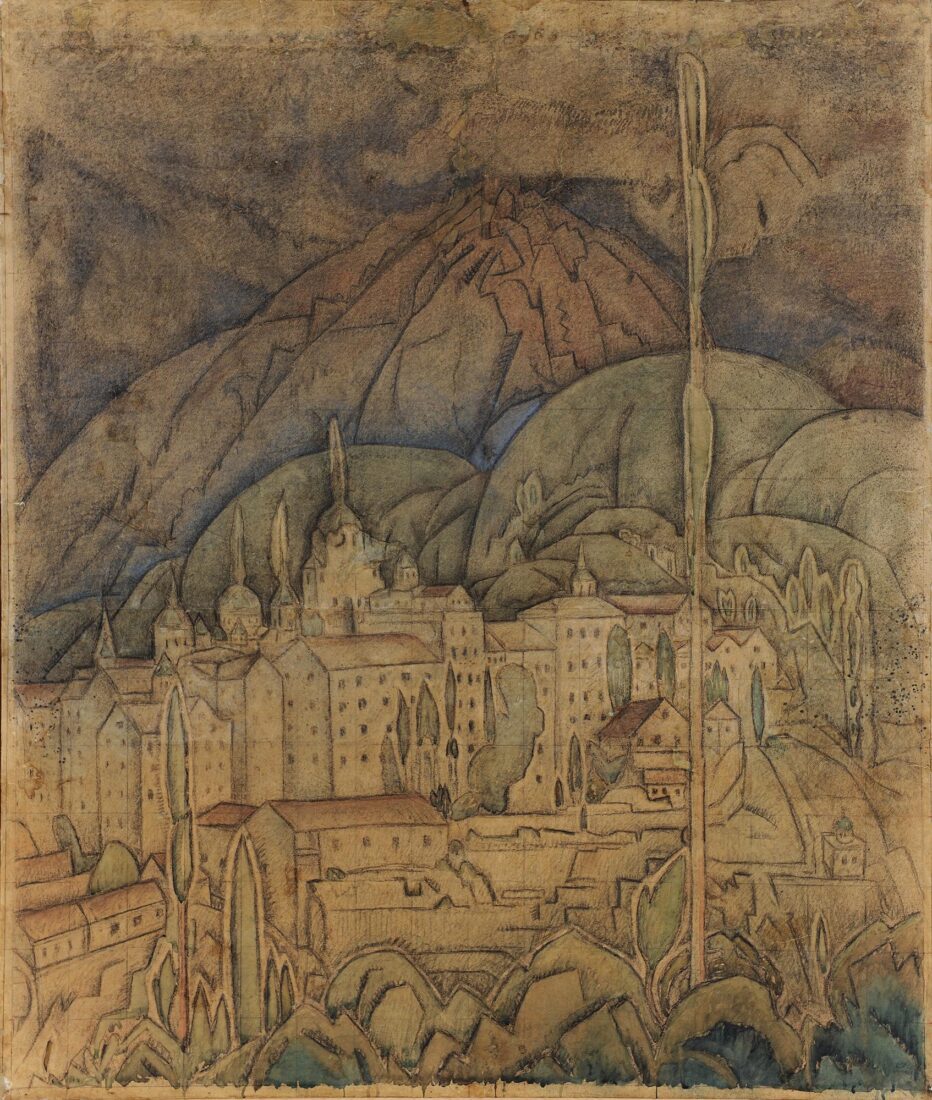

We have already met Konstantinos Parthenis in his first creative period, that of outdoor painting. After 1920, he turned towards anthropocentric, symbolist and allegorical subjects. With its powerful stylisation and light tonal palette, which makes his nimble, tall and thin figures seem like dreamlike projections on the canvas screen, Parthenis’ mature style had fully developed by this period. His works painted in this style seem like poetic reverie.

In the Thirties, certainly under conscious or unconscious influence by the predilections of that generation, Parthenis’ style changed. The curvilinear forms noted earlier now gave their place to a linear, angular writing, which often seemed to be supported by drawing instruments, such as the ruler and compass. Another notable change, probably related to Kontoglou’s return to the values of Byzantine art, was that the fresh, jubilant spring colours of the previous period were now replaced by the Byzantine palette and its earthy colours – brown, grey, dark blue. A common element with the previous period is the light hand, almost not human, which allows the canvas to show through and transforms the figures into dream-like fantasies projected on the painted surface.

Let us now “read” this monumental painting, an apotheosis, according to its title, of the great Greek revolutionary hero, Athanassios Diakos, who died a martyr’s death, near the Alamana Bridge on April 24, 1821.

The following lines are attributed to him by folk tradition:

Oh, that Death chose to take me now,

when the twigs are in full blossom and the soil is covered with fresh grass.

The artist seems to have had these lines in mind while making this monumental work, one of the crowning masterpieces of modern Greek art. He identified the hero’s resurrection and ascension with Christ’s Resurrection, both events occurring in the spring, around the month of April. On the left, a haloed figure, an Angel or one of the Myrrhophores, is startled upon discovering the empty tomb of the resurrected hero. In the middle, another angel, wearing a helmet and carrying a spear and shield, reminding us of a Christian goddess Athena, witnesses the miracle. Athanassios Diakos, in a classical chiton, rises in heaven, where he is received by angel musicians, similar to those in Greco’s paintings, while others are bringing laurel wreaths in order to crown him. A girl, as if out of Botticelli’s “Spring”, is sprinkling the hero with flowers from her lap. Incense is burning in a tall classical incense burner. The painting elevates the Greek Revolution into the sphere of the ideal world. The idealisation of history is also achieved through the symbols and the iconographical spirituality of the work.

In “The Apotheosis of Athanassios Diakos”, various influences, both iconographic and stylistic ones, join and blend: The drawing echoes classical pottery. The hero’s resurrection and ascension comes from the related Byzantine iconography. Flora, the personification of Spring in Botticelli’s work of the same title, is the iconographical source of the girl on the right.

Greco’s tall and slender mannerist figures, as well as his bipartite arrangement of his works in an earthly and heavenly section have inspired the morphology and composition of the Apotheosis. The geometric shapes and broken outlines, where space and form mingle with each other, reveal the Cubist* influence on Parthenis. Moreover, his cerebral, anti-naturalistic colours also originated in Cubism. This influence was reinforced by the shift towards the Byzantine tradition by the “Generation of the Thirties”.