“The Healer” is one of the eight pictorial images that surrealist painter Rene Magritte “translated” into three-dimensional form.

Magritte had a precise idea of what he wanted to achieve and went about finding the ideal means to execute these sculptures. For “The Healer” he made a plaster cast from the feet of a live model, and did the same for the bird cage.

“The Healer” has a number of features characteristic to Magritte’s enterprise, including the element of the unexpected, the extraordinary within the ordinary, and the mysterious. This sculpture, variations of which can be found in at least four of his paintings, came from a photograph that Magritte took in 1937, titled “God on the Eight Day”.

Although he was a painter, by translating eight paintings into sculptures, Magritte provided a different perspective on the function of objects and forms. Detached from the confines of the picture plane, they are placed in the space as autonomous presences and, through the change in scale, become different entities.

The subject of this piece is taken from the parable of the Prodigal Son as narrated in the Gospel according to Luke. The younger of two sons asked his father to divvy up his fortune and give him his share. The son then took the money, left home and squandered it in a foreign town, where he succumbed to hunger. Unable to sustain himself, he recalled that the slaves in his father’s household were living better that he was. So, repentant, he returned home, entreating his father to take him in as a slave, saying, “Father I have sinned against heaven and before you, and I no longer deserve to call myself your son.” His father, however, welcomed him with open arms and restored him to his rightful place in the home.

The moment of the Son-Man’s apology to the Father-God is depicted in a stance of intense supplication, with the figure’s torso straining backward and hands upraised towards heaven.

This piece synopsizes Rodin’s artistic ideals. Opposed to the imitation of reality pursued by the conservative academic artists of his day, he created powerfully expressive, deeply symbolic sculptural forms through the use of poses with excessive physical tension. The body here is muscular and sinewy, modeled with deep groves and incidents that heighten the sensation of agony, passion and desperation. Regarding this piece, Rodin confessed to Paul Gsell (Auguste Rodin on Art and Artists, p. 11) that he emphasized the muscle mass to express misery and in some places exaggerated the stretched tendons to make the outburst of remorse and entreaty more obvious.

Although this scene involves at least two persons, the son and the father, the presence of the latter is intangible, implied only by the movement of the son’s body and upraised hands.

This piece was shown for the first time in 1894 as The Boy of the Century at the Salon organized by the newspaper La Plume. However, it was exhibited with its current title at a pavilion of Rodin’s works at the 1900 Exposition Universelle in Paris.

The source of this figure is La Porte de l’Enfer (The Gates of Hell), from which Rodin isolated and developed a number of subsequent images. He frequently used variations of the same figure in different images, giving them different significance. The Prodigal Son comes from Fugit Amor, a group on the right section of the Gates. This monumental work was commissioned for the entrance of the future Musee des Arts Decoratif in Paris, but was never completed. Rodin nevertheless continued to work on it until his death, and its imagery resulted in a number of free-standing sculptures.

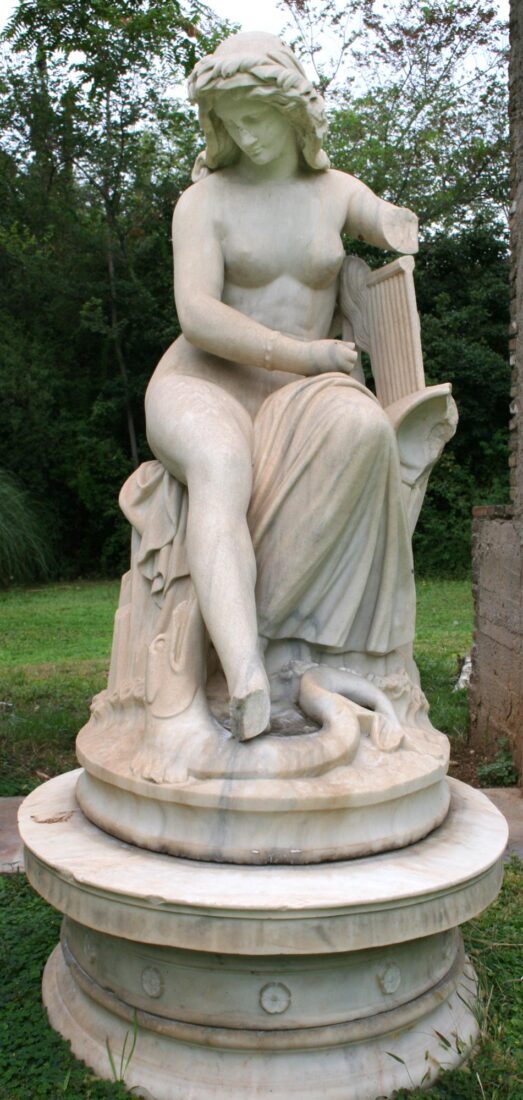

In 1949 Nikolaos G. Iliopoulos presented six marble sculptures to the National Gallery; he had inherited them from his uncle Nikolaos I. Iliopoulos and they had been placed in the garden of the former Thon villa, which was destroyed in December 1944. These sculptures are signed works – four by Georgios Vroutos and one by Georgios Fytalis. The only one that does not bear a signature is “Nymph”, but it was also thought to be a work by Georgios Vroutos and was recorded in the archives of the National Gallery under the title “Water-Nymph”, while in the report by the experts on the evidence obtained from the destroyed villa, it is referred to under the title “Fryni”. But the original attribution to Georgios Vroutos does not stand.

In 1841 the neoclassicist sculptor Ludwig Schwanthaler was commissioned to make a Nymph to be placed in a like-named room in the Anif Palace near Salzburg. Schwanthaler finished the work in marble in 1848. In 1852, with a few insignificant changes in the model, it was cast in bronze for the Royal Garden of Munich, while in 1855 the original or perhaps a copy was presented at the International Exhibition of Paris. In 1906 the original work was transferred from the Nymphs hall to the arcade of the palace where it fit in with the romantic exterior environment.

The “Nymph”, an idealized female figure with long wavy hair decorated with a wreath, is seated on a rock by the edge of the water holding her lyre with a melancholic and somewhat otherworldly expression, while a fish plays at her feet. The pose of the figure expresses thus the romantic spirit of the times in regard to the harmonious coexistence of the human being and nature, and brings to realization similar personal perceptions of the sculptor himself.

The “Nymph”, which came to the National Gallery in 1949, reproduces with almost perfect fidelity the original composition by Schwanthaler and leads to the conclusion that it is yet another copy of the work by Schwanthaler.

The head of the “Warrior Apollo” was a milestone in Antoine Bourdelle’s sculpture. It is the piece that marked his departure from the influence of Rodin and inaugurated his new style. Bourdelle’s personal style was formed along the guidelines of Archaic art and the austere order.

The Apollo of this composition was modeled after an Italian youth with a fiery, gaunt face, and evokes the figure of the ancient god who towers above the Battle of the Centaurs on the western pediment of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia. With this figure’s tectonic structure, sharp planes, austere expression, and powerful inner force, Bourdelle presages Cubism even as he remains faithful to Greco-Roman tradition.