Architect Lysandros Kaftantzoglou was the very successful director of the School of Arts from 1844 to 1862. Moreover, he was the one who designed and built the Technical University. Nikephoros Lytras painted his portrait from a photograph, shortly after the architect’s death.

Serious and contemplative, the great architect is sitting slightly turned to the side in a luxurious easy chair, over which he has thrown his greatcoat with a certain nonchalance. He is facing the viewer but is in fact gazing towards infinity. The artist perhaps intended to suggest in this manner the scholar’s recent death. Nikephoros Lytras here proves himself a penetrating psychologist, true to his own saying that, “the portraitist must draw from his sitters what they feel in the depths of their souls.” The architect is holding a small book, his index finger marking the page on which reading was interrupted. His right hand rests on a table, on which are scattered bits of paper and other items, splendidly captured.

The painting is made in broad, assured brush strokes, with a gentle palette of brown-red, along with grey-green, ochre, black and some white. Note the red scarf in the pocket of the greatcoat on the chair. With its monumental size, this painting is one of the most imposing portraits in the 19th century.

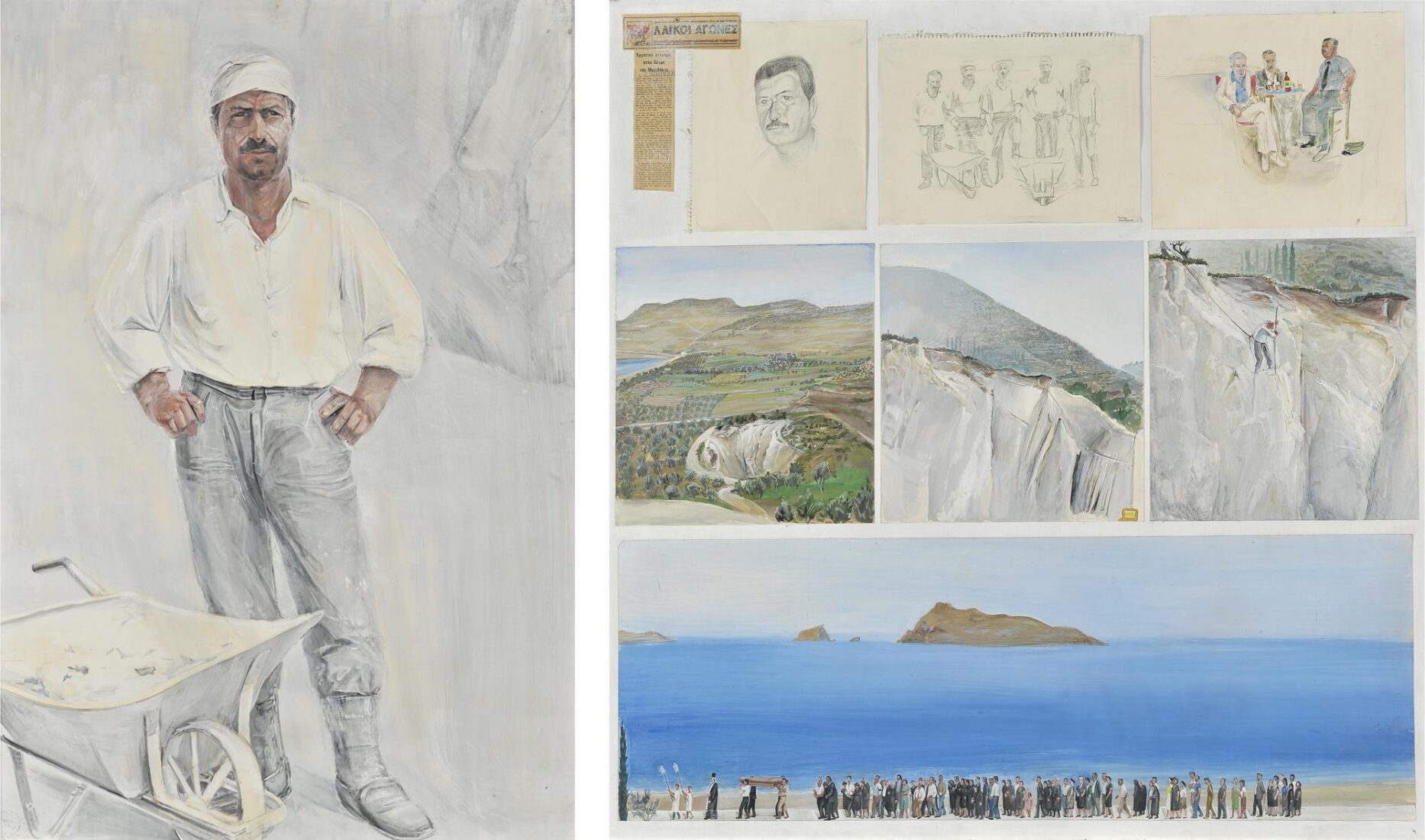

As this painting and the “Areios Pagos” by Lembesis were produced during the same year, 1880, and their makers were friends, they may well have been made at the same time, as was the habit of Impressionist painters. It is interesting to compare the two paintings in order to find out how two painters coming from two different schools – Lembesis from Munich and Pantazis from Brussels – approached the historical rock of the Areios Pagos on a summer day. Let us first see the elements they have in common: the two paintings share the same dominant colour tonality, based on the interplay of gold-yellow ochre on the rock and grey-blue in the sky. In both paintings, shades are purple. Therefore, both painters are familiar with the Impressionist “recipe.” So, where is the difference to be found? In “writing,” in brushwork, and in rendering volume. Lembesis’ writing is meticulous; he draws and captures every detail in the subject. The rock, on the other hand, maintains all of its compactness, it is solid. On the other hand, let us see how Pantazis, who is more of a true impressionist, approached his subjects. His technique is utterly different. Here, free brushwork can be seen at work, “building” the form. The rock is not trapped within a closed outline; rather, it is an open form. Also note the sky and the clouds, rendered in the most agile brushwork. In the dry Attic light, of course, forms maintain their shape, they are easy to draw clearly. One is therefore at a loss as to which painting is the most faithful interpretation of reality.

This monumental circular composition by Konstantinos Parthenis depicting the over-life-size head of Christ rivets the eye of the visitor to the National Gallery. Christ, here a mature bearded man wearing the crown of thorns, turns his tearful, agonized gaze heavenward. A torrent of yellow-gold light replaces the halo and bathes the divine face, bestowing on it an otherworldly glow and emphasizing its modeling.

The humanized dogma and the dramatic rendering of the Passion belong to the iconography of the Catholic Church as it was formulated in the time of the Counter-Reformation and dominated the Baroque (17th century). Parthenis’ Christ belongs to a typology frequently encountered in El Greco, but this specific composition appears to be inspired by a similar circular composition by Guido Reni. The subject, the emotional charge, the dominant blue palette, and the pointillist technique classify this mature work by Parthenis within the Symbolism of the Vienna Secession, where he did his apprenticeship as a young painter.