Yannis Gaitis is one of the most characteristic and original representatives of Pop Art in Greece. He was also recognized in France, where he lived for many years. Gaitis invented an archetypal stylized figure that was a concentration of the characteristics of a male inhabitant of mass consumer society. A standardized outline, black hair, a blue hat resembling similar figures painted by the Belgian surrealist Magritte, a striped or checked suit, all on a flat board of a body whose arms are stuck to its sides. This recognizable everyman became the trademark of Gaitis’ art. We see it multiplied and crowded together in many inventive compositions such as this piece, evoking today’s impersonal mass consumer society. Gaitis employed this archetypal symbol to formulate an acerbic social commentary through recognizable humorous and imaginative images that remained pleasing and decorative despite the unpleasant reality they condemned. The decorative striped and checked motifs and the limited but satisfying harmony of dark blue, light blue and white, which Gaitis used almost exclusively, contribute to the sense of euphoria that his work exudes.

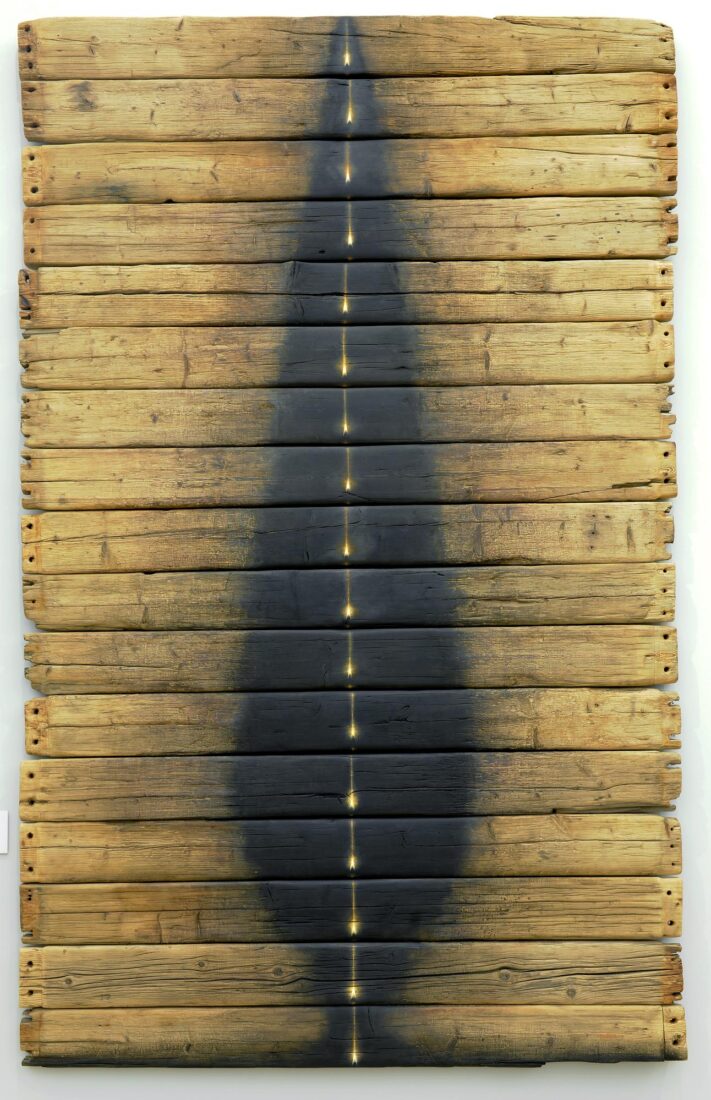

Christos Bokoros is one of a group of younger artists who returned to figurative painting, but with a renewed eye, in pursuit of a new meaning in the image. Bokoros is an explorer of memory. He is excited and moved by the traces that human life leaves behind – its labors, its pain, its joy and its hope. The life that has departed leaves behind anonymous imprints that the artist extracts from obscurity and silence to gives them new meaning. The materials he uses in his work bear the obvious signs of use and age: wood recovered from submerged slips, old boats, tables, rusted remains of vessels hallowed in human hands. On these materials, as on an altar, Bokoros reverently deposits his image. It is telling that the flame is the iconic image of his practice: a flame of a candle, a flame of a lamp, a humble flame symbolizing memory. It is the perpetual flame that burns before icons, the candle lit on Greek Orthodox Easter, the promise of eternity that exorcizes corruption.

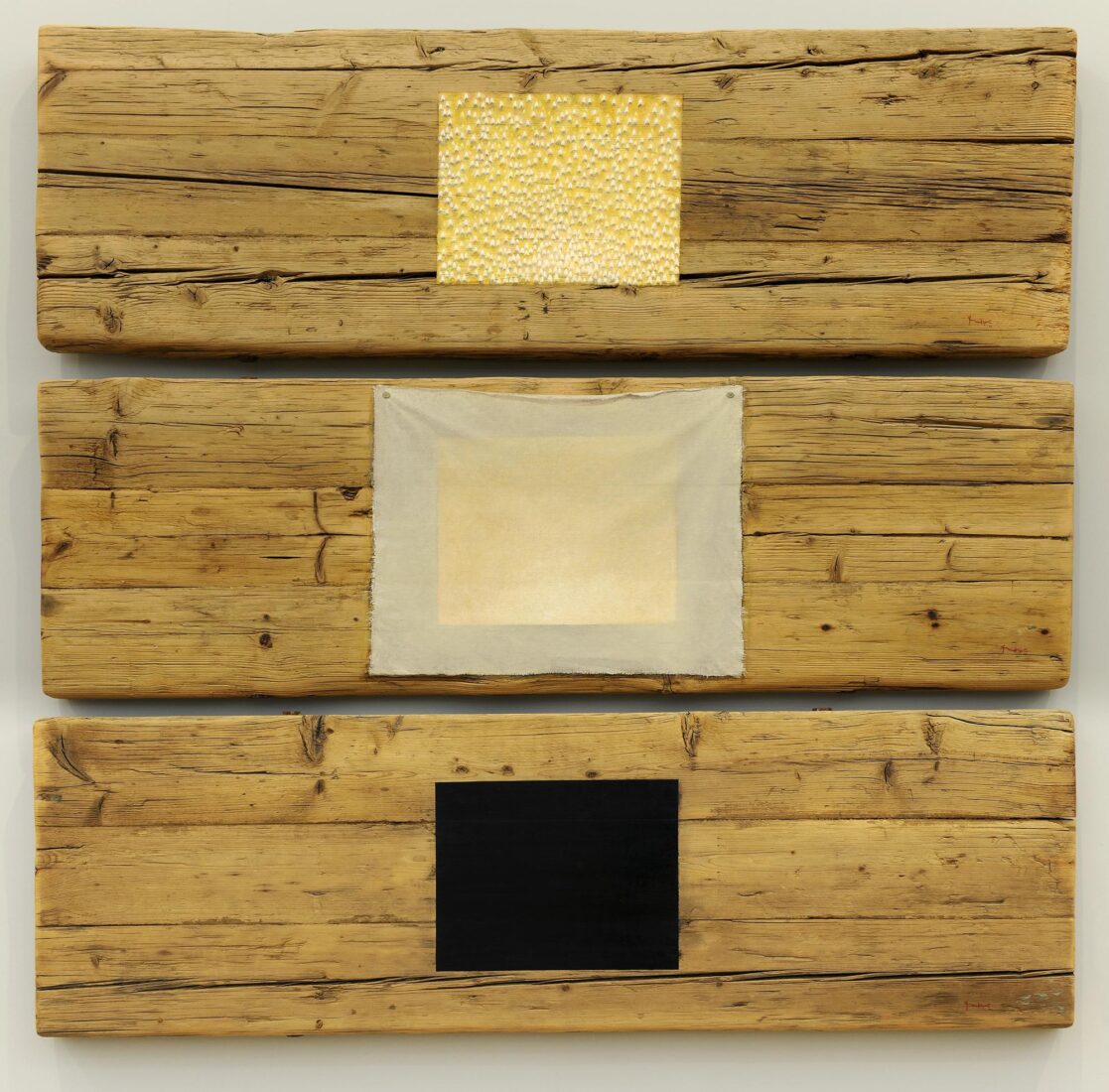

The Enigma of Parrhasius is an allegory. It narrates a story of painting, the adventure of form from Antiquity to contemporary art: the stormy seas it has weathered, the questioning it has undergone, and the painter’s faith in is endurance and survival.

The narrative unfolds in a triptych. Three horizontal weathered wooden boards, salvaged from an old bridge, are placed parallel to each other, ready, after suitable preparation, to receive the painted image. The first panel depicts a black square: a reference to the famous painting by Russian artist Casimir Malevich. At the time when this, the quintessential minimalist work of Suprematism was made in 1915, philosophers and critics rushed to pronounce the death of painting. The second panel leads us to a well-known incident told by Pliny the Younger (1st century AD), recounting two famous painters of classical antiquity who lived in the time of Socrates. Zeuxis and Parrhasius were competing, as was the custom in those days, for the honor of most perfect painter. This was the age dominated by the notion that imitation and perfection equaled verisimilitude. Zeuxis painted a basket of grapes so vivid that the birds were fooled and began pecking at it. Parrhasius chose to paint in a very illusionary manner a drape that supposedly covered his painting. When Zeuxis ordered him to remove the drape to unveil what he’d painted, Parrhasius replied triumphantly, “You succeeded in fooling the birds, but I have tricked the great painter Zeuxis. Therefore I deserve the title of victor.

In the second panel of the triptych, Bokoros has painted a piece of cloth on the square with such skill that it appears real. But behind in glimmers an imperceptible light. In the third panel the cloth has been removed to reveal a square field flowering with little flames. The message of the piece is clear: painting as it travels through time it can weather storms and be questioned, but in the end it always emerges the victor.

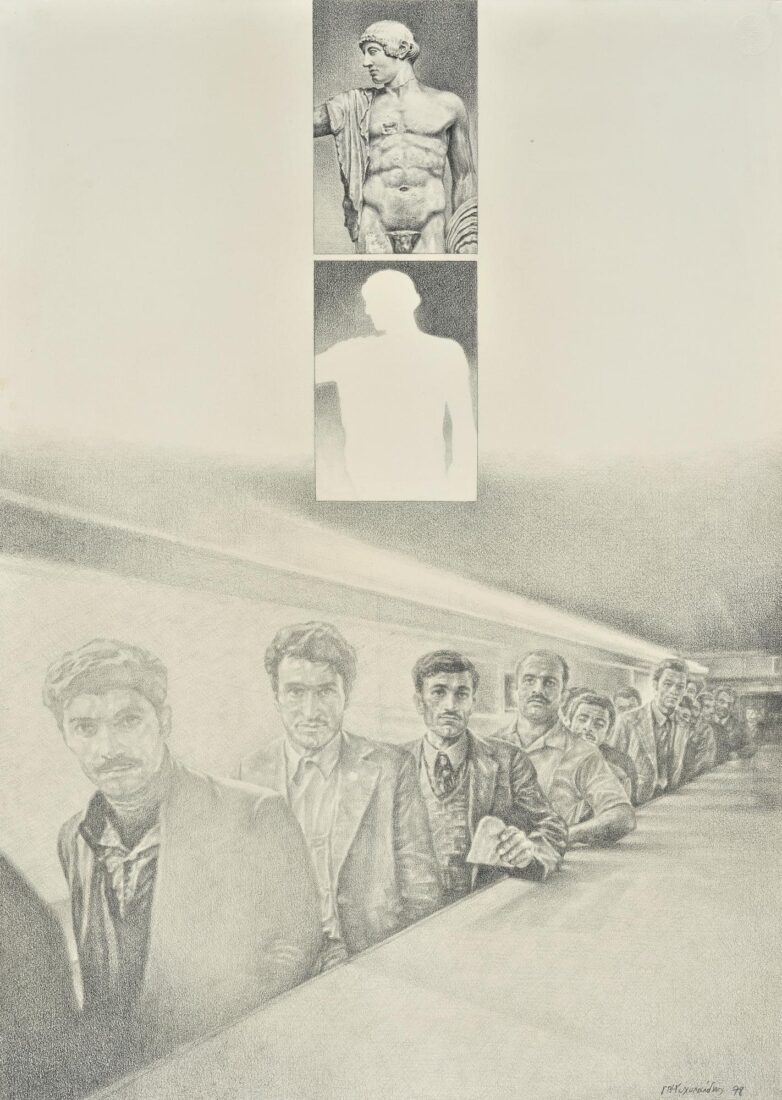

Giorgos Nikolaidis’ sculpture encompasses a broad spectrum of forms, from traditional anthropocentric representations to abstract constructivist compositions, as well as environments and installations. In his earliest pieces he focused on the human figure. The abstract tendency in these works gradually morphed into total abstraction.

In the 1970s Nikolaidis produced a series of sculptures in stainless steel, which he titled with numbers. These works are fashioned from segments of cylindrical shapes with pointed ends that coil freely and dynamically in the space or converge in various rhythmic combinations. The dominant feature is a perpetual circular or spiral movement that is immediately perceptible in some works but latent in others.

“1211A” is a characteristic piece from this series. Starting out from aggressive acute-angled shapes in its lower portion, it evolves into two cylindrical segments that seem to want to form a circle. The piece is incorporated into and coexists harmoniously with the surrounding space. At the same time, the space is defined by the shape and encompassed by it, contributing to the refinement of the sculptural form.