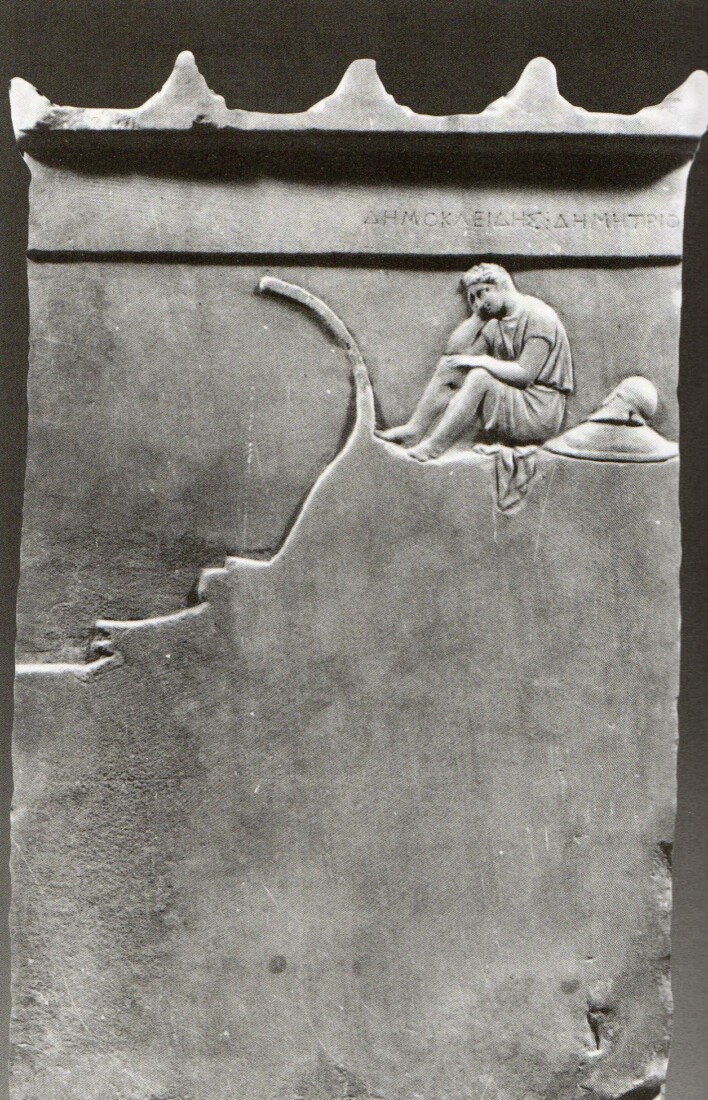

Demokleides was very young still, almost an adolescent, when he was called upon to serve his native city on a trireme. We may never know how he came to die so young. Was it in a glorious naval battle, or in an unheroic storm? We see him now sitting in thought on the curved prow of a warship, his head resting pensively on his right hand, contemplating the immensity of his liquid grave. Behind him, no longer needed, his shield and helmet indicate that he was a hoplite (an infantry soldier); his rank follows him to the underworld.

What is it that makes this humble, small-scale early-4th century BC marble grave stele so special, so moving, so contemporary, and so extraordinary among the masterpieces in the National Archaeological Museum in Athens? The ancient sculptor had a bold vision – to convey the notion of the infinity of the sea by reducing the scale of the shipman figure, placing it at the top in the composition, and leaving a large space empty to envelop in silence most of the surface of the tombstone. It is this use of space that enhances the dramatic effect in this narrative. Not only does it speak of the immenseness of the sea, but of silence, solitude, the pain of an early death, of the unburied dead, the open wound of his loved ones, who were unable to adorn, mourn, and inter him as would have been fitting.

Even if this empty space was originally painted blue to suggest the sea, as archaeologists surmise, this is still a daring choice. We might be tempted to regard this composition as a very early manifestation of minimalism, the art of less. An arrangement of such intense drama would have been inconceivable in the classical 5th century BC, when citizens felt safe and protected within the city boundaries. After the Macedonian expansion and Alexander’s conquests, later on, with the explosive outspread of the boundaries of the known world that came with them, the citizen was transformed into the individual; art now reflected the solitude, anxiety, and insecurity he felt. It is not a coincidence that the stele of Demokleides was one of the few ancient artworks selected by the distinguished art historian Jean Clair to illustrate the theme of melancholy in the eponymous monumental exhibition he curated in Paris (Grand Palais, Oct. 2005 – Jan. 2006).

Was Demetrios, the father of the prematurely lost shipman, in fact able to weep and mourn the dead lad? Did he have this moving stele placed to mark a cenotaph? We will never know. Three centuries later, the Roman poet Horace dedicated an ode to a shipwrecked sailor and his plea to any passing sailors to perform the due rites of burial (Horace, Odes, Book I, ΧΧVIII).

The theme of mourning for a sailor lost in the watery wilderness brings another artwork to mind: The Dirge of Psara by Nikephoros Lytras (ca 1888) – a painting that depicts in disarming simplicity, immediacy, and truth a scene that the inhabitants of the Greek islands would experience too often. In a sparse island home interior, women and children have gathered to silently mourn the sailor lost at sea. They are seated in a circle (reminiscent of the tragic chorus) around a red fez that stands for the absent dead. The tragic figure of the father is depicted bowing, alone, in the shadowy right-hand side of the image. An impromptu iconostasis has been set up on a chair on the right. The overturned stool in the foreground stands for the absence of the dead, while at the same time accentuating the third dimension in the composition. The scene is filled with a restrained yet pervasive sense of tragedy. The painting adopts an almost monochromatic palette of browns, the only vivid colour being the red of the dead sailor’s fez. Sketching the figures in wash, in a confident, free hand, Lytras proves especially daring here.

The Dirge of Psara is a major painting in the history of Greek art of the 19th century, for it not only combines authentic emotion and an extraordinary modern style but, above all, it truly reflects the life of the people, a far cry from the nostalgic, idealised, often saccharine genre paintings by Munich School artists.

Marina Lambraki Plaka

Professor Emeritus of the History of Art

Director, National Gallery – Alexandros Soutsos Museum

English translation: Dimitris Saltabassis