Introduction

“If they want to create something original, they should start with ‘a’, which stands for ‘Anthropos’ (‘Humanity’)”. This was the advice the sculptor Christos Kapralos (1909-1993)[1] gave to young artists in an interview in the early 1980s.[2] He would go on in the same interview to refer for the first time on record to a series of sculptures from the second half of the 1960s, inspired by images of bombed villages in Vietnam: “One night, my eyes fell upon some photographs showing horrific scenes from the Vietnam War. They had a shocking impression on me. I cut out the photos from the newspaper, enlarged them and, through them, I created a series of figures, such as the wounded hoplite and the mother with the terrified child”.[3]

Between 1965 and 1969 Kapralos, a sculptor deeply attached in his work to human drama and to the quiet dignity of all those who, away from the frontlines of history, fight in times of war or state crisis, was able to focus his creative impulses on the pulse of the international human rights and peace movements of the era. In the middle of this five-year period, Greece would be caught in the vortex of the military junta (1967-1974), which would also affect certain sculptures of the series, assigning them further symbolic meaning.[4]

This synchronization between the artist and history produced six large bronze compositions and several smaller studies, with the supplementary or alternative title Vietnam, which to date have not yet been studied, published or exhibited as a thematic series, although they have appeared individually in art history publications and exhibition catalogues. [5]

Valuable sources for their identification have been the catalogue of the sculptor’s works, organised by his wife Souli Kapralos (d. 2012), as well as his photographic archive, which includes several thousand negatives and multiple-view prints of his works, always photographed under his supervision and with his specific instructions.[6]

The present paper, as well as bringing together for the first time all the sculptures of the Vietnam series in one publication, focuses on three main objectives:

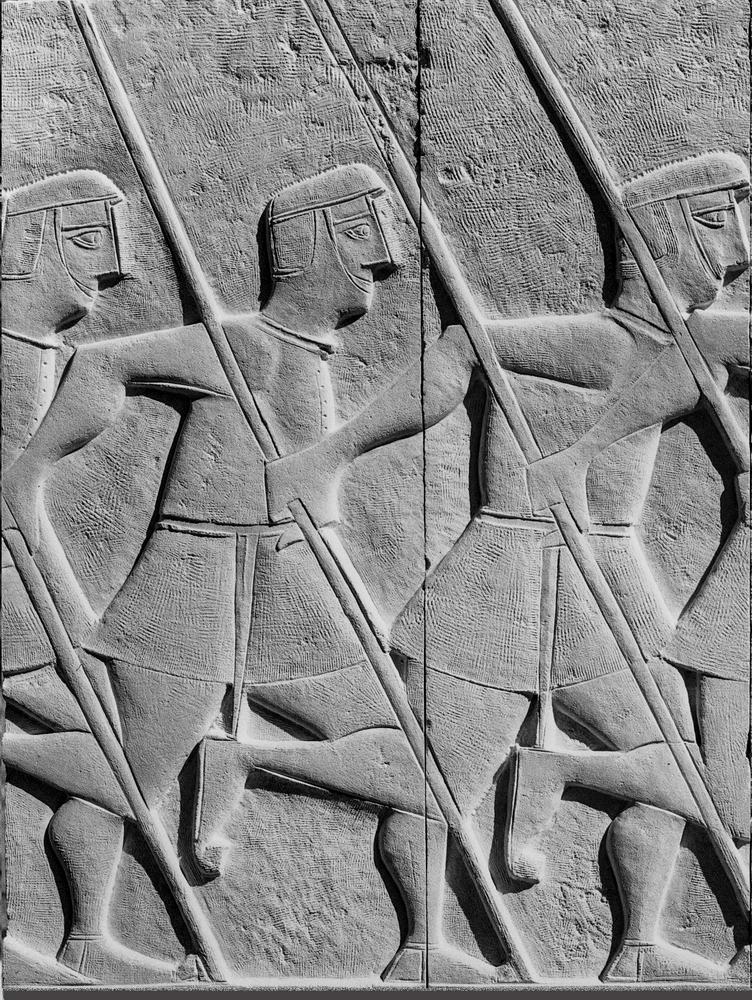

To examine the evolution of the series’ sculptural forms, by tracing, where possible, the ‘genealogy’ of their basic iconographic types. We will investigate, for example, how the linear, almost two-dimensional frontality of the early Hoplites (fig. 24-25) evolved into the freestanding and fleshy expressionism of the 1969 Wounded Hoplite-Vietnam (fig. 22a-c).

Secondly, to explore the process whereby meaning is assigned to the works, by focusing on Kapralos’ specific use of titles and the ambivalent interpretations this sometimes dictates. We will consider, for example, how some sculptural portraits made from life in 1963 (fig. 7-9) were transformed into the large Bather-Vietnam (fig. 6a-b) and its small-scale variations (fig. 10-12).

Finally, to draw on the works’ formal qualities and narrative content to reveal some of their common features, in order to highlight the position of the Vietnam series in Kapralos’ œuvre and, hopefully, its importance for modern Greek sculpture.

The Works

Based on their subject-matter, the sculptures of the Vietnam series can be divided into five groups: Mothers with Children, Bathers, Women as Commodity, Pairs of Clashing Figures and Wounded Hoplites.

Mothers with Children

This is a dominant subject throughout Kapralos’ œuvre, running through all his stylistic periods, techniques and materials, and is represented in this series by a large sculpture (fig. 2) and three small-scale variations (fig. 3-5). The compositions were based on an iconic image from the Vietnam War by the award-winning German photographer Horst Faas (1933-2012) (fig. 1), which was published uncredited in a 1966 anti-war feature in the art journal Epitheorisi Technis.[7]

In the photo, the flames that burn this mother’s village are raging behind her, while she, an archetypal and universal symbol of life and protection, has grabbed her two children and is running away to save them. In the large sculpture, the figures of the composition form a tight triad, “cut out” from a trapezoidal frame, possibly an allusion to the original rectangular photograph. The infant’s upper body and the mother’s right hand are fragmentary, while the baby in her arms is a relief emerging from her heart. The tension of the figures’ movement is located in the lower halves of their bodies, their only means of escape.

Although this is an important work in Kapralos’s oeuvre and a cast of the piece has been on public display in Athens since 1989[8], it has to date only been exhibited and illustrated with the title Composition.[9] This neutral labelling, which has largely determined the interpretation of the sculpture, was a choice made by Kapralos himself, despite the fact that on the viewer’s right side of the frame he had engraved the word ‘VIETNAM’. This ‘de-historicization’ of the Vietnam sculptures through the selection of neutral titles will be discussed in subsequent sections of the paper.

In the smaller scale variations on this theme, there are two notable elements. Firstly, the depiction of the mother in fig. 4, with her torso bent and leaning forward, is reminiscent of the pose found in the sculptures Daphne[10] and Lapith Woman[11], mythological figures whom Kapralos also depicted being chased and running for their lives. Secondly, the mother and child composition in fig. 5 refers to the iconographic type of the Vrefokratousa (‘Virgin Mary Holding Baby Jesus’), except that here the harmony and serenity of the embrace are dramatically disturbed by the abrupt twist of the desperate mother’s right arm.

With this group of works, Kapralos went beyond the formal and interpretive limits of his iconographic source to pay tribute to non-combatant mothers throughout history and their children, the most innocent of all the victims of Vietnam, as with every war.[12]

Bathers

Kapralos started creating variants on this theme, according to Souli Kapralos[13], in the summer of 1963, inspired by his observations of a female neighbour, who would go down to the beach in front of their house-cum-studio on Aegina every day. As such, the Bathers-Vietnam are the result of an interesting conceptual transformation; from the wax and cast plaster portraits of the elderly ‘Mrs Pantou’ (fig. 7-9), who walked in and out of the sea with her slow, fragile step, always holding the gaze of her observer, to this mourning bronze female figure (fig. 6a-b) and its smaller versions (fig. 10-12).

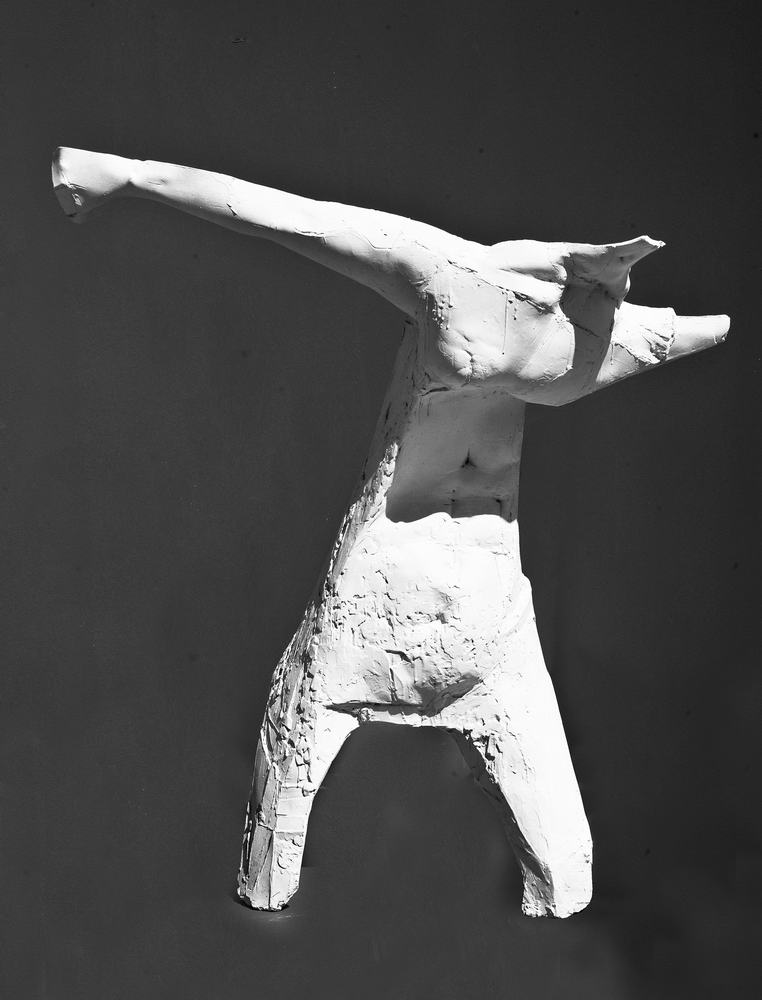

The large Bather-Vietnam stands with her upper body tilted, legs extended, her right arm outstretched in an expressionist, diagonal axis, her left severely bent in the ‘trademark’ posture of Kapralos’ Mothers[14], supporting not only her head, but also her collapsing body. To date, the sculpture has been illustrated only as Bather and, certainly, without the explanatory remark found in the Kapralos Archive, its link to the Vietnam War could never have been established.[15]

Therefore, who is the subject of Kapralos’ large Bather-Vietnam, within the interpretative context this new archival information allows us to situate her? A witness to a tragic war scene? A victim among the stricken civilians? Or a personification of the grief that accompanies every war? It is both all of these together and each one separately. Two additional interpretive keys may be offered by the testimony of Souli Kapralos regarding what the sculptor had confided to her about the making of the Bather 1968 (fig. 9): “It’s for you that I didn’t break this sculpture. I had two problems with the position of the arms. For a moment I thought it was not going well. I pushed it to knock it down. To destroy it, but it resisted. Then I thought I would upset you and so I kept it. Now I am happy. This is how I want the arms, like wings. I want the sculpture to equally resemble a scarecrow and a tree […]”.[16]

Bather-Vietnam could be a long-suffering tree, standing upright against the sufferings of war; Bather-Vietnam could also be an apotropaic figure, with the power to avert the calamities of war.

Women as Commodity

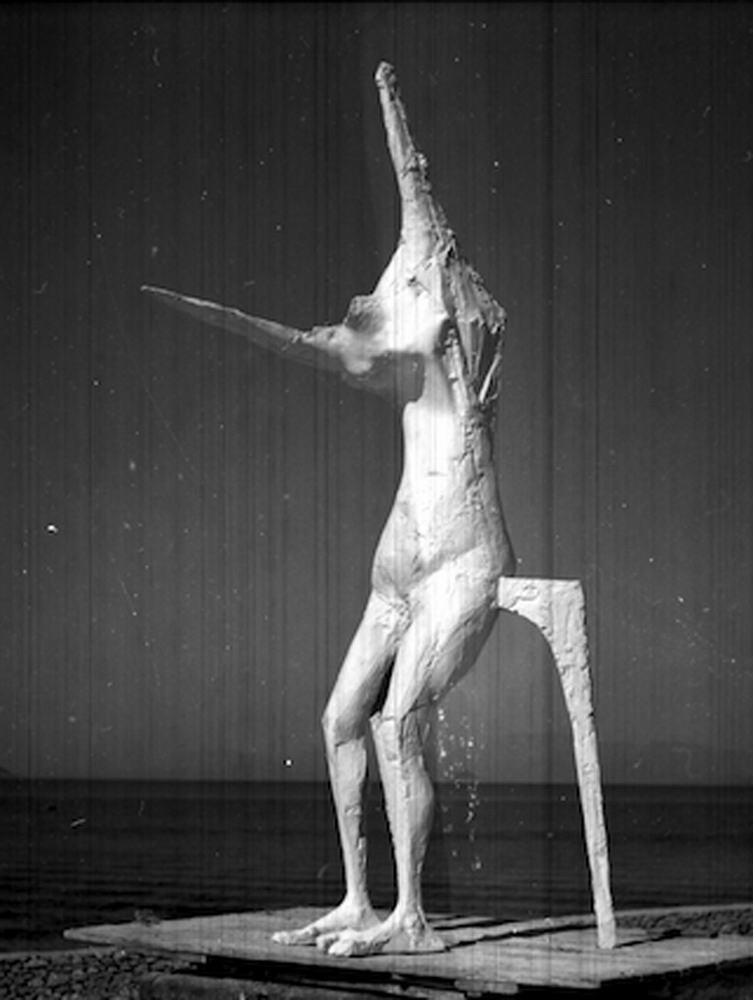

The most elusive group of the series includes two large compositions, Theater-Vietnam (fig. 13a-b) and Door-Vietnam (fig. 15), as well as a small study of the first (fig. 14).

In Theater-Vietnam, a naked female figure sits behind a tripod structure with a set of sharp, upright ends on the top, reminiscent of Minoan consecration horns, a feature also found in Kapralos’ stone carved seats.[17] A wide opening at the level of the seated figure’s chest and abdomen might also represent a cash desk, and above and below the horizontal edges of this form the breasts and abdomen of the female body reappear in relief. The engraved inscriptions ‘THEATER’, over the breasts, and ‘VIETNAM’ on each of the pointed ends, imply that we may be standing in front of a ticket office, in a queue for a perpetual show starring the prostituted female body, which during the Vietnam War, as in every war, offered its services as a living commodity and as a bounty for looting.

At the bottom of the Door-Vietnam composition these fragmentary female figures appear again, similarly exposed: the figure on the viewer’s right, with her back turned, seems to be looking for a way to escape or a place to hide; the other figure on the left, is a frail, fleshless figure with two empty cavities on her chest instead of tight curves, her breasts depicted as negative imprints.

This interpretation of these two compositions has been proposed based on comments by Souli Kapralos to the author. In literature, however, both sculptures usually appear simply as Compositions,[18] again restricting a more precise interpretive approach, in this case an exploration of the exploitation of the female body in wartime.

Following the Mothers and the Bathers, this is the third thematic group of the Vietnam series that focuses on the female figure; once again, Kapralos here praises the resilience, endurance and strength of women’s roles in the theatre of history.

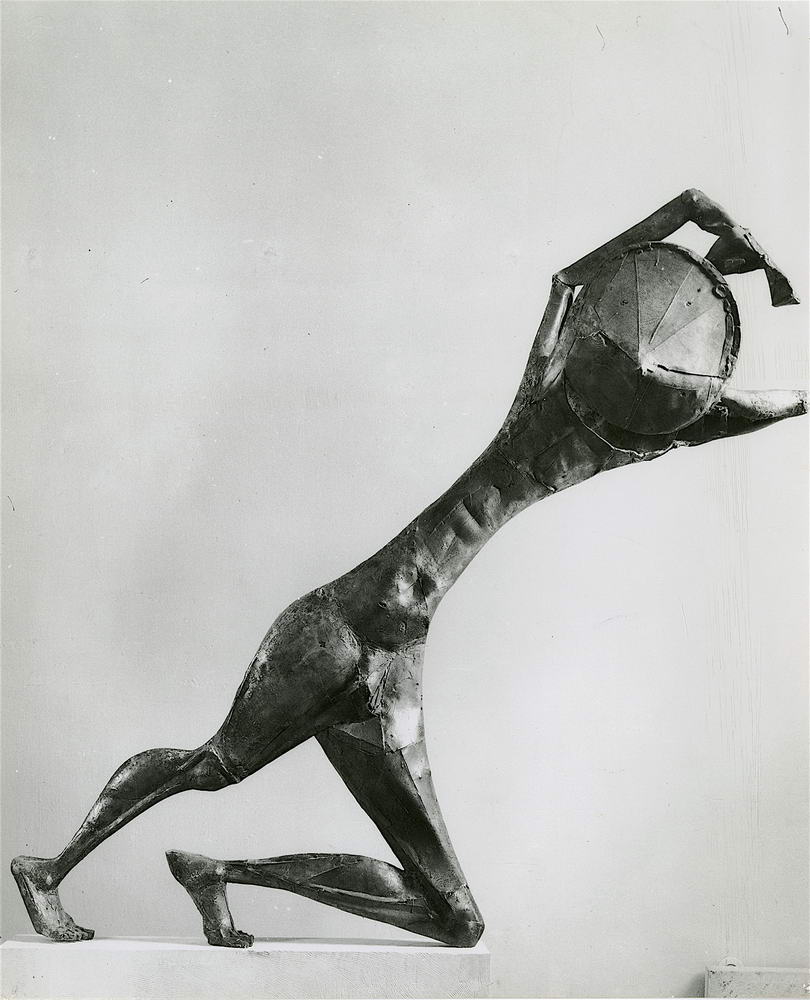

Pairs of Clashing Figures

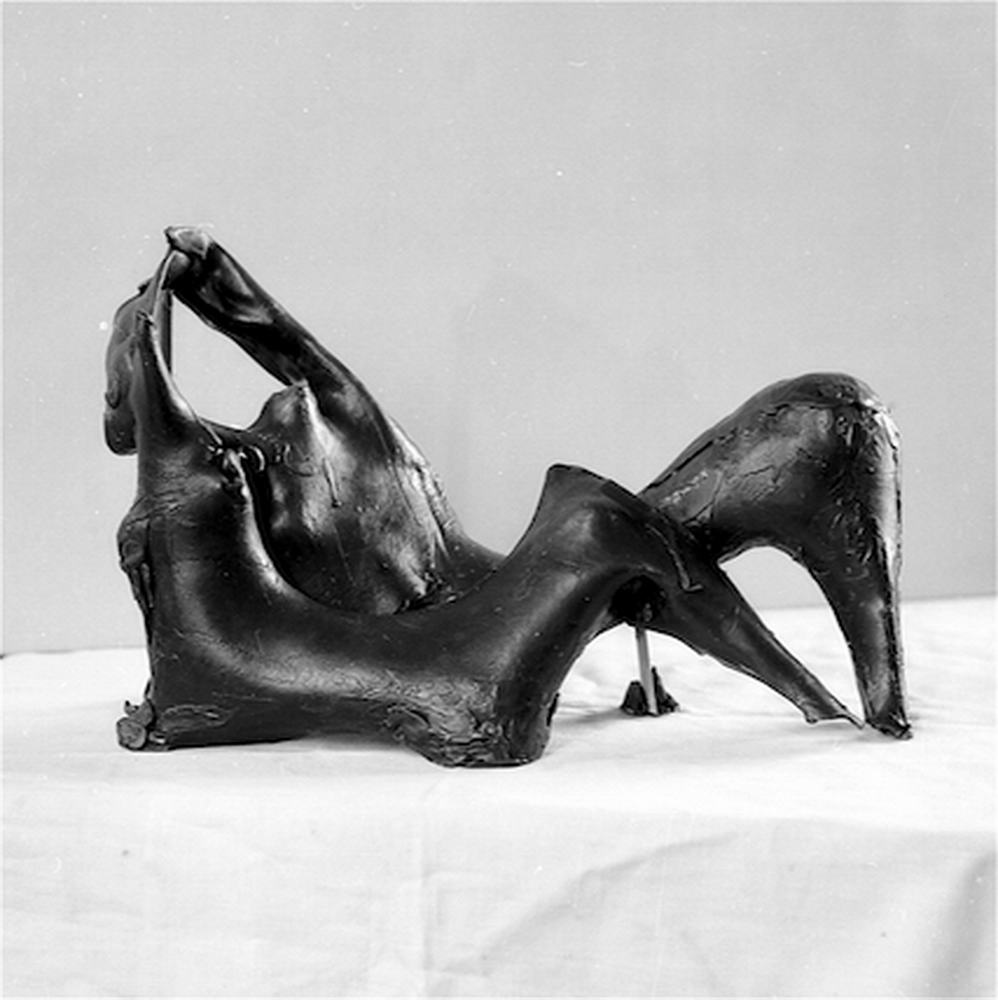

The central sculpture of this group is the 1967 piece Vietnam (fig. 16a-d), the first composition of the series illustrated and later exhibited under this title.[19] It is also the only one whose engraved inscriptions on the front, «ΒΙΕΤΝΑΜ Νο. 2» (‘VIETNAM No. 2’) and «ΔΙΧΤΑΤΟΡΙΑ ΑΙΣΧΟΣ» (‘DICTATORSHIP SHAME’), assigns an explicit political meaning with an anti-American undertone to the work, as they connect the Vietnam War with the 1967 Colonels’ coup and the overthrow of democracy in Greece.[20]

A captivating, freestanding sculpture, Vietnam stands out for the many angles it can be observed from and for its compositional originality: it can be viewed as one body divided in two at a thigh-high level, or two bodies morphed into one with a shared lower half, at the moment of their tragic collision. The attacking, headless figure on the viewer’s right side is depicted in motion, with its left arm bent upwards thrusting its invisible weapon against its opponent, who resists, remaining upright, its left arm extended horizontally, its right held by its torso with a clenched fist.

The 1967 Vietnam does not depict a brave confrontation or a heroic episode from a battle, but a tragic scene: a human being ready to strike a fellow human, a brother or sister with common roots and common destiny, since, as they share one body, the annihilation of one means the automatic annihilation of the other.

For this reason, I suggest that this two-figure composition is a reprise of an older iconographic theme, which Kapralos had developed first in a study (fig. 17), then in a scene from the ‘Resistance’ section (fig. 18, detail) of the forty-meter frieze Monument to The Battle of Pindos (1951-1956), which, in my opinion, alludes to the 1946-49 civil conflict that scarred Greek Post-War history.[21] In the 1967 sculpture, Kapralos’ mature style has moved away from the realistic representation of his earlier work and has erased the identity, ethnicity and specific gender traits that define the stone carved couples of the 1950s. Most significantly, however, it has created a union of the two figures into one, an element that reveals the deeper meaning of the composition and, consequently, of the thematic group.

The theme is further emphasised in two more abstract, small-scale variants (fig. 19-120), while some notable terracotta pieces from the same period, such as the one pictured here (fig. 21), demonstrate Kapralos’ interest in exploring the theme of the clashing pair in various materials.

Wounded Hoplites

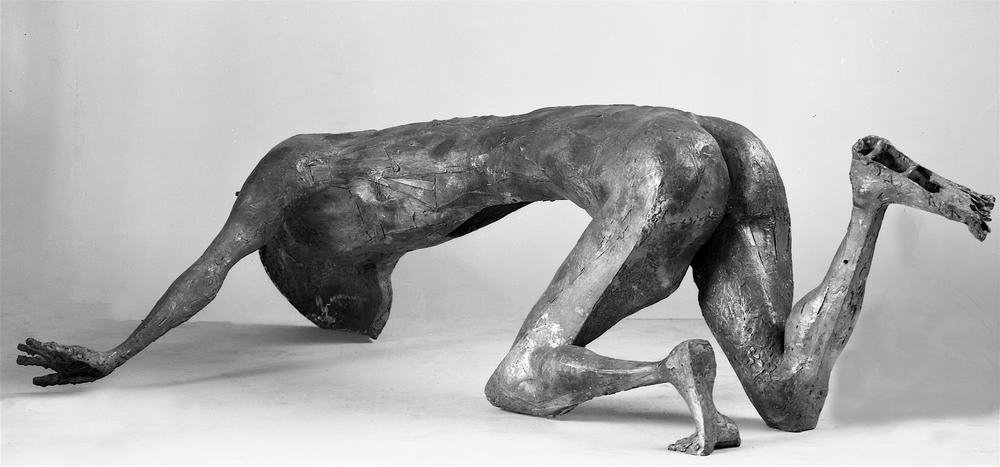

The Wounded Hoplites are the subject in this series with the richest visual and conceptual ‘stratigraphy’; however, none of Kapralos’s Wounded Hoplites of the second half of the 1960s are catalogued in his archive under the title Vietnam and it can only be presumed that they could be included in this series due to the testimony of the artist himself in the aforementioned interview of the 1980s.

From this series, therefore, we can only safely include the Wounded Hoplite of 1969 (fig. 22a-c),[22] although we will also juxtapose images of smaller variations on this theme from the same period (fig. 28-31) and discuss its iconographic evolution through earlier versions of the subject (fig. 23-27).

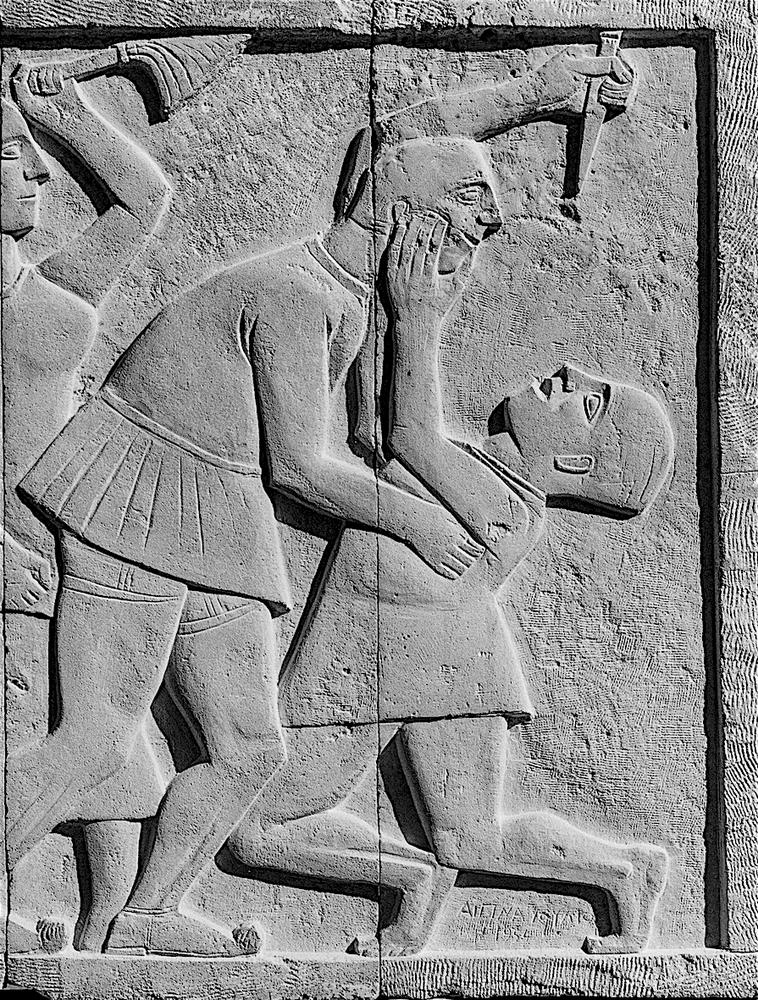

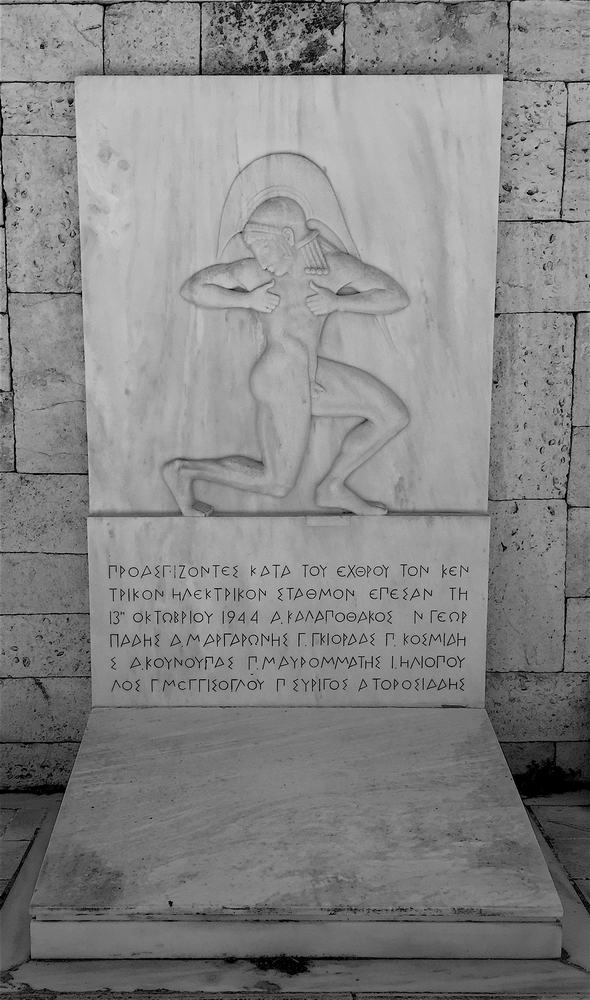

The type of the hoplite was first introduced very early in Kapralos’ iconographic repertoire. The figure was first used in 1948, when he copied the well-known relief Hoplitodromos (ca. 500 BC) in the National Archaeological Museum for his Memorial to the Fallen in the Battle of the Power Station (fig. 23).[23]

This early connection of the ancient Greek iconographic type with modern history was repeated eight years later with the hoplites carved in relief for the Monument to The Battle of Pindos (fig. 24). In these early works, Kapralos’ hoplites were robust, combative warriors.

His first wounded hoplite was a lead sculpture from 1957 (fig. 25), which today belongs to the Municipality of Rhodes Museum of Modern Greek Art. In 1963, the assassination of Grigoris Lambrakis, a doctor, pacifist, marathon runner and MP for the United Democratic Left (ΕΔΑ), led Kapralos to temporarily rename the 1957 kneeling figure, which was then illustrated in at least four of Lambrakis’ obituaries under the title Dying Marathon Runner.[24] It is no surprise, then that later, during the military dictatorship, the 1969 Wounded Hoplite (fig. 22a-c) was incorporated by its creator in the anti-war Vietnam series.

This large sculpture, that probably draws its iconography from the wounded hoplite of the eastern pediment of the Temple of Aphaia on Aegina (ca. 490-480 BC),[25] could also be juxtaposed with an important work with the same theme by Henry Moore (Fallen Warrior, 1956-7), which is also considered to express the tragedy of war, in this case WWII.[26]

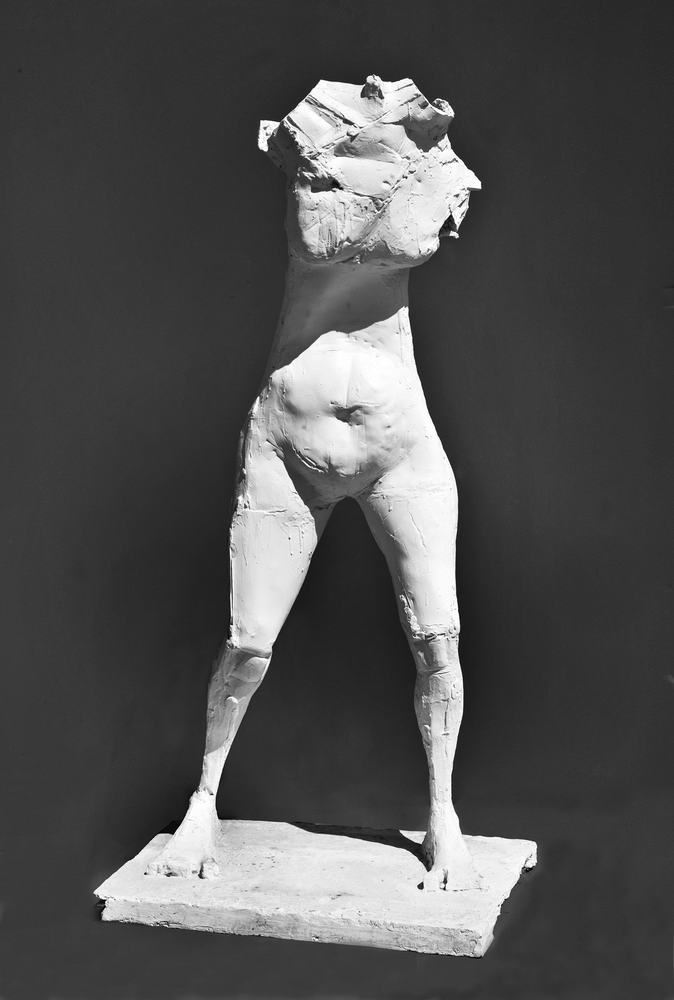

The 1969 Wounded Hoplite is depicted in a prone position, on his knees and leaning on his shield, holding it as an extension of his right hand. Headless, as Kapralos is not interested in his identity,[27] with his elongated torso full of sculptural ‘scars’ and his left arm stretched out dramatically, not quite touching the ground, he looks like he will be unable to get up on his feet again.

The linear, plane-based frontality of the 1950s Hoplites has here evolved into a dramatic corporality, achieved by the combination of bold angles, as in the right leg, and vigorous curves, as in the buttocks.

The intermediate stage in this development, seen in two Wounded Hoplites from 1961 (fig. 26) and 1962 (fig. 27) respectively, is closer in style to the 1969 Wounded Hoplite, except that the exaggerated pose of the first and the bold fragmentation of the second create a space around the sculpture, keeping the viewer at a distance. By contrast, the somewhat ‘performative’ quality of the posture and rendering of the 1969 Wounded Hoplite, engages the viewer, inviting you to follow its movement step-by-step and gaze at its sculptural features from every viewpoint, and perhaps even to imagine yourself in a similar fall. This characteristic is also featured in four small-scale variations of the theme (fig. 28-31) made between 1965 and 1967.

Concluding Remarks

As is made clear from the above analysis, the Vietnam series is not a group of works Kapralos created with the intention of exploring sculpturally a predetermined subject. Instead, it resulted from a spontaneous and non-systematic process of receiving and responding to artistic stimuli that originated from the shocking events of the Vietnam War. This process included a series of reprises and reinterpretations of past iconographic types that had been important to him since the beginning of his sculptural explorations.

This partly explains the individualised and often decontextualized presentation of the sculptures, rather than as a contained series. Another possible interpretation for this is related to the historical circumstances of their creation: we should take into account that the beginning of the five-year period between 1965 and 1969 coincides with the peak of Kapralos’ international career, which included solo exhibitions in America,[28] while the last three years were the first years of the military dictatorship in Greece, whose regime had in many ways suppressed freedom of artistic expression.[29]

In any case, the present paper attempts to reconstruct the formal and conceptual threads that unite the sculptures of the series and to highlight the importance of archival research for the original readings it allows. Ultimately, the revelation of previously unknown aspects of works of art leads to the activation of fresh interpretations.

Thanks to these life-giving properties, art brings meaning to our individual presence and our social coexistence. It is often born from a successful synchronization between artists and history, subsequently acquiring a key social function, at the heart of which lies the struggle for human rights: freedom, democracy, equality and the end of discrimination.

Aside from visualising an amazing call for peace – an indisputable prerequisite for all of the above – Kapralos’ Vietnam series is a remarkable artistic confirmation of the fact that before, after and beyond military history, political analysis and ideological conflict, there is human life at its very core, and the essential premise that everyone should have exactly what they need and deserve as humans.

In this light, the Vietnam series is a timeless tribute to Humanity [ΑΝΘΡΩΠΙΑ], a word that begins and ends with an ‘a’.

Artemis Zervou

Curator at the National Gallery – Alexandros Soutsos Museum

October 2020

[Conceived, researched and written in the context of the National Gallery’s participation in the Digital Cultural Programme of the Hellenic Presidency of the Council of the European Union, May-November 2020; translated from Greek by the author; English text edited by William Summerfield]

Notes

[1] For a bio of the artist see, Zervou, Artemis, “Christos Kapralos 1909-1993”, in Yannis Moralis – Christos Kapralos. A Friendship in Life and Art [exh. booklet], Athens, 2016, pp. 38-41.

[2] Φραντζής Φραντζισκάκης, «Ο Χρήστος Καπράλος απαντά σε δέκα εάν», Ζυγός, no. 45, January-February 1981, pp. 30-43.

[3] Ibid., p. 43.

[4] For the response to the Vietnam War by the Greek Peace Movement during this period see, Makris, Alexandros, “The Greek Peace Movement and the Vietnam War, 1964-1967”. Journal of Modern Greek Studies, vol. 38, no. 1, 2020, pp. 159-183. Project MUSE, https://doi.org/10.1353/mgs.2020.0008 (accessed: 18 October 2020)

[5] The images of the six central compositions of the Vietnam series, as well as their smaller scale variations, are highlighted with a blue caption, so that they can be distinguished from Kapralos’ sculptures featured in the paper as iconographic models of the series.

[6] Where possible, unpublished archival images of the works were selected for the illustration of the present paper. The scanning of negatives and a minimum digital processing were executed by photographer Thalia Kymbari.

[7]«Ο πόλεμος που ντροπιάζει κάθε άνθρωπο», Επιθεώρηση Τέχνης, no. 141, September 1966, pp. 166-171.

[8] In 1989 it was purchased by the Municipality of Athens and installed at Rallou Manou Square, on Amalias Ave, near Syntagma. See, Σαββανή, Ειρήνη. «Σύγχρονη Γλυπτική στην Αθήνα», newspaper Η Καθημερινή, supplement «Επτά Ημέρες», tribute Τα γλυπτά της Αθήνας, 25 October 1998, pp. 28-30; Αντωνοπούλου, Ζέττα. Τα γλυπτά της Αθήνας. Υπαίθρια γλυπτική 1834-2004. Athens: Ποταμός, 2003, p. 193. In 2009, the cast was transferred to the renovated Rizari Park, where it stands to this day.

[9] See, for example, Χρήστος Καπράλος. Γλυπτά από χαλκό 1960-1980, [exh. cat.], Athens: National Gallery – Alexandros Soutsos Museum, 1981, p. 35; Χρήστου, Χρύσανθος, Χρήστος Καπράλος. Athens: Παπαστράτος ΑΒΕΣ, 1981, p. 108-109; Λυδάκης, Στέλιος. Οι Έλληνες Γλύπτες. Η Νεοελληνική Γλυπτική: ιστορία, τυπολογία, λεξικό γλυπτών. Athens: Μέλισσα, p. 349; Λεξικό Ελλήνων Καλλιτεχνών: Ζωγράφοι, Γλύπτες, Χαράκτες 16ος-20ός αι., vol. Β, Athens: Μέλισσα, 1998, p. 128.

[10] See, Daphne Ι (accessed: 18 October 2020)

[11] See, Centaur and Lapith Woman (accessed: 18 October 2020).

[12]It is estimated that half of the approximately 3.000.000 Vietnam War victims were Vietnamese civilians. As far as infant casualties are concerned, it is worth mentioning here an emblematic anti-war work about the so-called ‘My Lai Massacre’, the 1968 poster “Q. And Babies? A. And Babies” by the New York group Art Workers Coalition. See, https://www.moma.org/collection/works/7272 (accessed: 18 October 2020).

[13] Καπράλος, Χρήστος. Αυτοβιογραφία [συμπληρωμένη από τη Σούλη Καπράλου]. Athens: Άγρα, 2001, pp. 176-177.

[14] See, Mother (accessed: 18 October 2020).

[15] See, for example, Χρήστος Καπράλος [exh. cat.], op. cit., p. 34; Χρήστου, op. cit., pp. 112-113; Καφέτση, Άννα and Παυλόπουλος, Δημήτρης. Θεόδωρος Στάμος – Χρήστος Καπράλος: από τη Συλλογή του Ζαχαρία Πορταλάκη, [exh. cat.]. Heraklion: Δήμος Ηρακλείου, 1998, pp. 174-175. The sculpture was presented for the first time under the title Bather from the Vietnam series in the exhibition Yannis Moralis – Christos Kapralos. A Friendship in Life and Art, co-curated by the author and held at the Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Center, from 21/9 to 18/12/2016.

[16] Καπράλος, op. cit., p. 177.

[17] See for example, Anthropomorphic Seat – Crete (accessed: 18 October 2020).

[18] For the fig. 13 work, see, for example Χρήστος Καπράλος [exh. cat.], op. cit., p. 18, s/n 31; Χρήστου, op. cit., p. 121; Καφέτση and Παυλόπουλος, op. cit., pp. 148 and 176-177. Παυλόπουλος probably recognizes the female figure’s identity, since he wonders whether she represents a ‘vessel of erotic hedonism’ [‘σκεύος ηδονικού ερωτισμού’, ibid. p. 148]. For the fig. 15 work, see, Χρήστου, op. cit., pp. 118-119.

[19] As Βιετ Ναμ [Viet Nam], it illustrates March and April in the 1973 wall calendar of Pisteos Bank; as Βιετνάμ [Vietnam] makes part of the permanent exhibition of the National Glyptotheque: see, Giannoudaki, Tonia, National Glyptotheque. Permanent Collection. Athens: National Gallery-Alexandros Soutsos Museum, 2006, pp. Elsewhere, the sculpture is published as Σύνθεση [Composition]: see, for example: Χρήστος Καπράλος [exh. cat.], op. cit., p. 36· Χρήστου, op. cit., pp. 114-115.

[20] That same year, Kapralos created a series of ten small-scale anti-dictatorship sculptures, entitled April 1967. See, for example April 1967 (Mother’s Lament)

[21] See, Ζερβού, Άρτεμις. «Ίχνη του Εμφυλίου στην ιστορική διαδρομή της δημιουργίας, της έκθεσης και της υποδοχής του Μνημείου της Μάχης της Πίνδου του Χρήστου Καπράλου». Historica, no. 65, April 2017, pp. 175-194.

[22] The sculpture has been published only as Hoplite; See, for example, Χρήστος Καπράλος [exh. cat.], op.cit., p. 39· Χρήστου, op. cit, pp. 128-129.

[23] See, Ζερβού, Άρτεμις. «Μνημείο Πεσόντων στη Μάχη της Ηλεκτρικής: σύντομο χρονικό μιας παραγγελίας του διοικητή της Ηλεκτρικής Εταιρείας στον γλύπτη Χρήστο Καπράλο», in Μαυροειδή, Μ. and Πανσεληνά, Γ. Μ. (eds.). Έτσι σώθηκε η ΔΕΗ. Μια μάχη στην καρδιά της Απελευθέρωσης [exh. cat.], Athens: ΔΕΗ Α.Ε., 2017, pp. 30-33.

[24] Επιθεώρηση Τέχνης, no. 101, May 1963, p. 466· newspaper Αυγή, 26 May 1963· newspaper Αυγή, 26 October 1963· newspaper Αυγή, 24 May 1964. It is worth mentioning here the sculpture Athlete (1963) by Kostas Koulentianos (1918-1995), installed in 1971 as a memorial to Grigoris Lambrakis in the eponymous Bologna, Italy square (Piazza Lambrakis). See, http://www.chieracostui.com/costui/docs/search/schedaoltre.asp?ID=26425 (accessed: 18 October 2020)

[25] See, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:East_pediment_-_Temple_of_Aphaia_in_Egina_-_Glyptothek_-_Munich_-_Germany_2017.jpg (accessed: 18 October 2020)

[26] See. https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/moore-falling-warrior-t02278 (accessed: 18 October 2020).

[27] Χρήστου, op.cit., p. 14, points out that “[The head] is, to some degree, a reduction of the general to the particular, the universal to the individual, the eternal to the transient. But this does not seem to interest an artist who, through the human body, aims to create the primary, the essential and the collective”.

[28]To mention but two examples, the Cincinnati Art Museum hosted a large solo Kapralos exhibition from 21 April to 28 May 1967. See, Christos Capralos. A Modern Greek Sculptor, [exh. cat.], Cincinnati, Ohio: The Cincinnati Art Museum, 1967; in the same year, Kapralos represented Greece, along with Yannis Gaïtis, at the Pittsburgh International Exhibition of Contemporary Painting and Sculpture.

[29] See the forthcoming publication of the proceedings of the conference Εικαστικές τέχνες και αρχιτεκτονική κατά την επταετία 1967-1974: θεσμοί, ιδεολογίες, ρωγμές και αδράνειες, organized by the Society of Greek Art Historians on 28 April 2017, at the Macedonian Museum of Contemporary Art [updated 11 July 2021: the e-publication of the volume can be found in https://eeit.org/3d-flip-book/oi-technes-sti-diktatoria/]